In 2021, Emily Jones Hudson founded the Southeast Kentucky African American Museum and Cultural Center, which seeks to share the stories of African Americans in east Kentucky left untold in popular understandings of Kentucky history. In an interview with ORVI, which has been edited for clarity and length, Hudson discusses how the Great Migration, coal’s busts, and “urban renewal” changed what were once significant Black communities in Perry County, Kentucky.

She explains how modern development should focus more on the needs of people instead of just physical infrastructure, and how she sees the Center as a force for reconciliation in mountain communities. “In order for healing to take place,” says Hudson, “there needs to be that conversation around whatever caused the wound.” Hudson hopes the Center can help communities come to a common understanding of lessons from the region’s past and build on “what we share in common as people living in this region so that we can move forward.”

There is a famous photo of Robert Kennedy on Liberty Street in the Black community in Hazard. What has happened to that community, and where does it fit in the history of Perry County?

It was just amazing how many Black folks were here in the 1930s and 1940s when coal was really booming. I’ve seen some of the pictures of the coal mine camps right across the river, Bluegrass. And Liberty Street was a Black community here. There was a Black school, Liberty School, that had grades from elementary all the way up to high school. The way some of the people that I’ve interviewed describe that community, that’s what it was: a community, a family. The high school was the center point.

The photo of Robert Kennedy was taken right before all the changes came to Liberty Street. I don’t know why they chose that community, but it was going on all over Hazard. There was a street—it’s called Peach Street—right off Memorial Drive, where the whole area there was a Black community. Blacks lived on the property there. They had stores, businesses, and when that “urban renewal” came, it’s just like it vanished. I pastor a little church, the block building sitting by the health department at the foot of the hill. And during the 1930s or 1940s, that little church set somewhere else. They actually moved it to where it’s located right now. So, it’s like they came in and just rearranged everything.

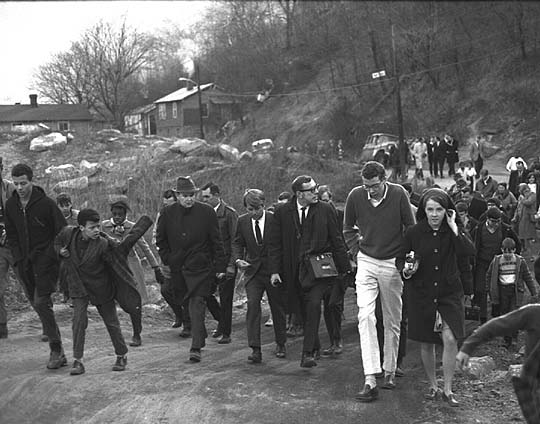

Robert Kennedy in Hazard, KY.

When the coal boom went bust, and the demand for coal fell, just like white miners and white families, there were a lot of Blacks that migrated north. A lot of the Black families went to the big cities, and began work in the factories. So, we began to see the population of Black folks dwindling down. At the same time, I’ve interviewed multiple people who talked about how with “urban renewal” they came and took their community.

Residents of Hazard, KY walk alongside Robert Kennedy.

Were there schools that Black kids could attend in Hazard prior to integration, and how did they compare to white schools?

Before integration which took place here in 1956, they had a grade school out in the county on Town Mountain, Brown’s Fork School. At that time, you also had the elementary schools in the coal camps. It was segregated. You’d have the Black school and the white school. And of course, the white school was better equipped: it may have several rooms, and the Black school was usually one room. The supplies—the books and things—were hand-me-downs. It was the same way in the high schools. They got the discarded books.

I’ve been told some kids in that time period had to go away somewhere for school. You can imagine that would be a hard thing: to go to high school you have to go away somewhere. The first Black high school was in Vicco in 1928. It was called Higgins High School “Mountaineers,” and it was built on land that was donated by a Black preacher named George Higgins, and with Rosenwald funds. Students from Hazard caught a bus that went up there. The school began to grow and grow. And then they decided to build one here in Hazard.

In 1936 they built Liberty Street High School as part of the Works Progress Administration, and it was the Liberty Street “Dragons.” We now have the pictures of Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, George Washington Carver, and Benjamin O. Davis Sr. that hung up in the hallways at that school.

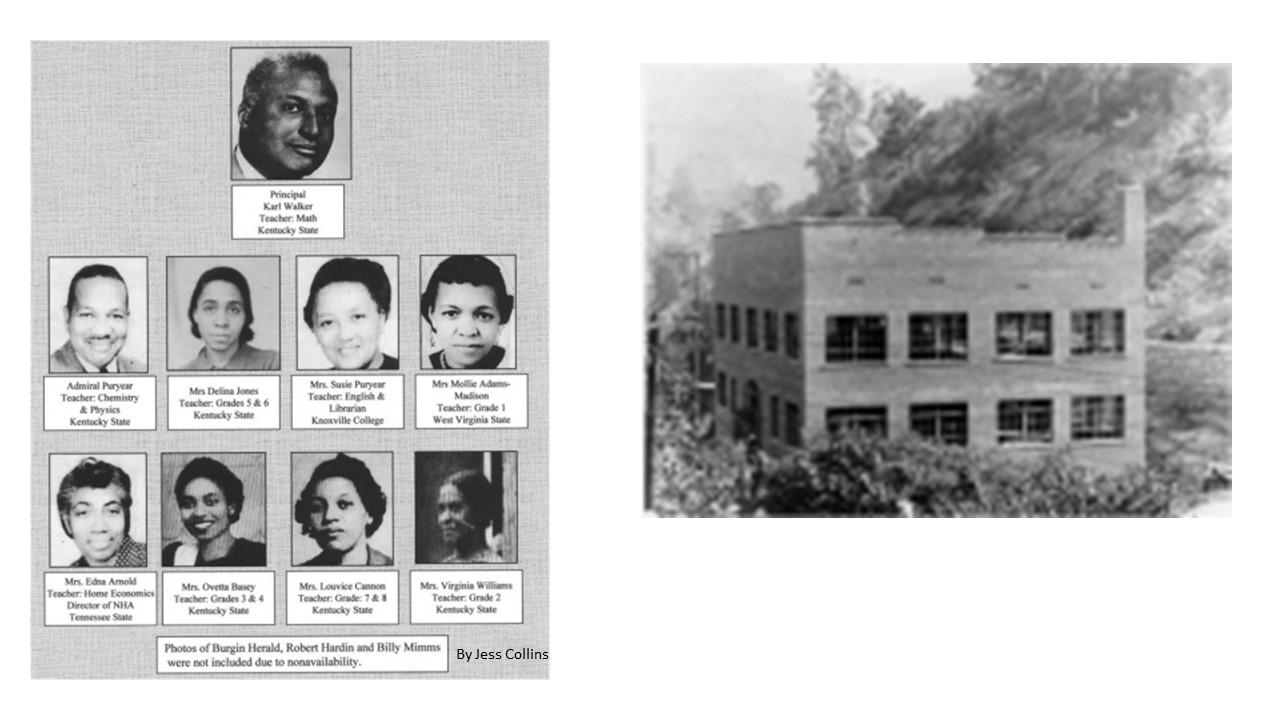

Liberty Street High School staff and grounds.

How do you think the experience of the students in those Black schools differed from the experience of Black students nowadays?

Several people that graduated from Liberty went on to become, you know, professionals. They credit their time under those teachers at Liberty High for their success. Because they didn’t take no junk. Those teachers were really preparing them for their next move in life, knowing the things that they would have to face, the challenges and so forth.

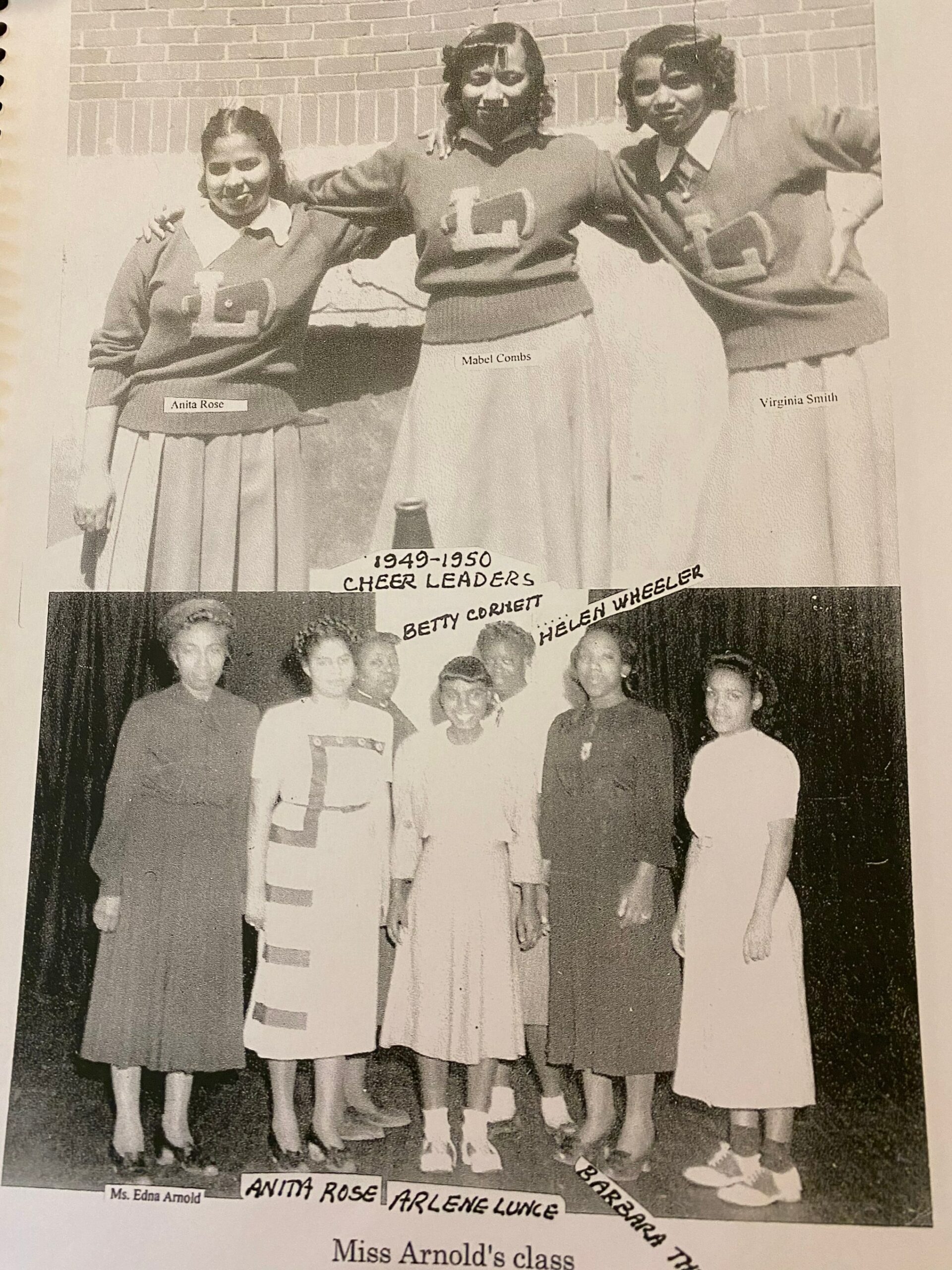

Students at Liberty Street High School, 1950.

That kind of mindset in the teachers toward the African American students, it’s not there these days. One of the reasons for that is that there aren’t any black teachers in our high school. But there was a certain relationship—those Liberty teachers knew what these kids would be facing, and they tried their best to prepare them. The teachers made sure they taught them about their history. We don’t have that going on in schools today—teaching Black history and so forth.

The process of desegregation varied across the South. What was desegregation like in Perry County?

When Liberty closed in 1956 it was the year of integration. A lot of the students went to Hazard High School. There were some that went to the county high school at that time, MC Napier. According to some folks I’ve interviewed, it wasn’t a smooth transition.

For example, Liberty had a great basketball team. There were colleges that were sending this one particular basketball player offers after he had started playing for Hazard High School, and he never got them. Because the coach put them in the desk drawer and never showed them to him. It’s, of course, a lot better nowadays, but the number of Blacks in the schools is smaller now than then.

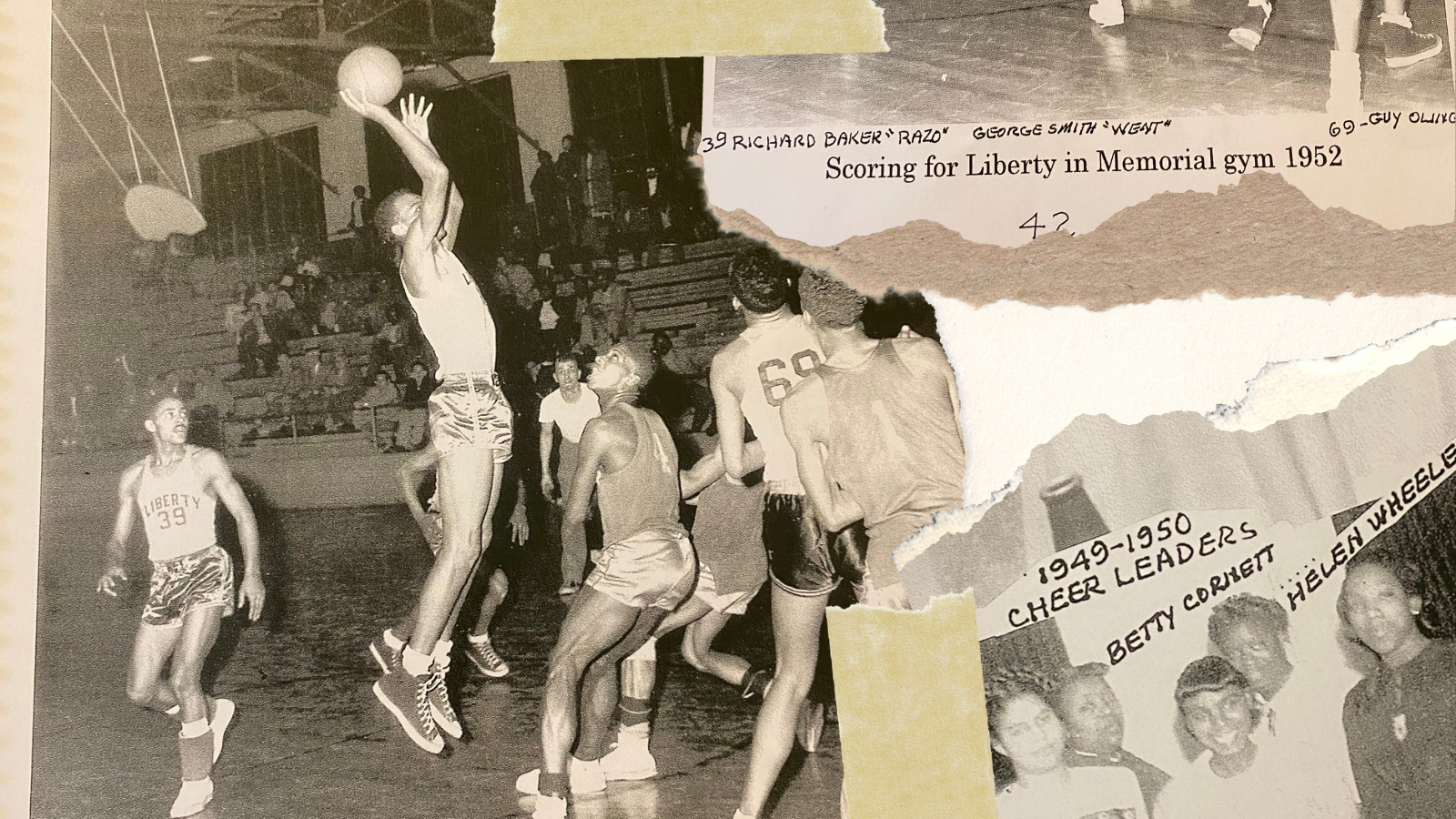

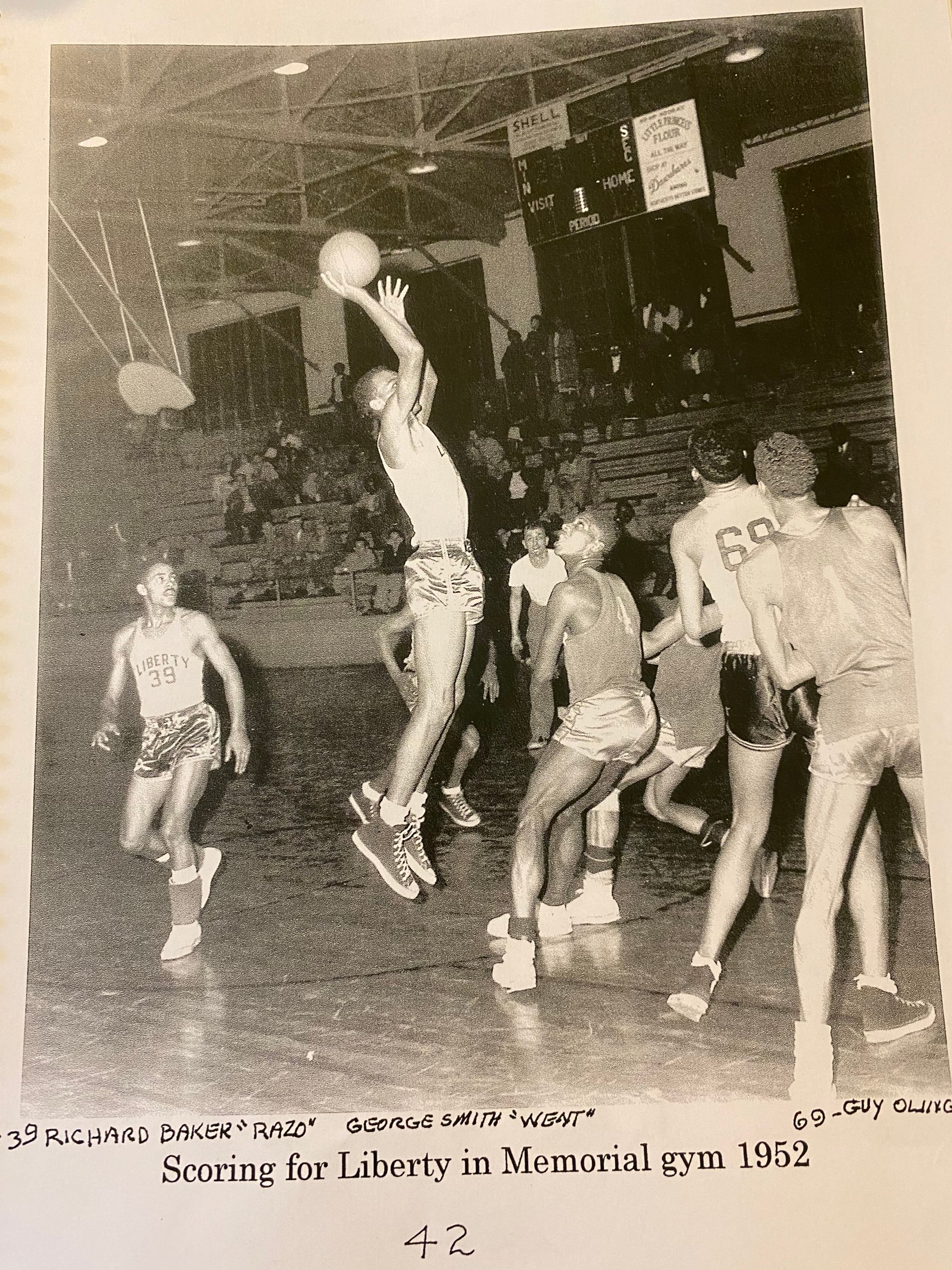

George Smith arcs a shot for Liberty High School in Memorial Gym, 1952.

As the “first draft of history” in Perry County, how have local newspapers covered the Black community over time?

We were recently researching microfilm and news in the area going all the way back to 1915. It seemed like any article that was written about a Black person—as short as it was—did not use their names. They just said, “negro man” or “negro woman.” Most of the time it was about someone killing someone or stabbing someone or drunk and getting in a fight. So it was that kind of a thing. Never any positive news. And I’m looking at that and I’m saying, “I know Black folks who are doing things—significant things—at this time.” But it never made the news.

As we went on in the research, we saw that they begin to use their names in news stories. I can’t remember the name right off, but [one story] was talking about how one Black man had died. It gave his name, and how he was one of the wealthiest Black men around. So, I’m saying: Who is this man? We kind of took that trip there, through the newspapers, and saw how the reporting began to change. Some began to report some positive things, but there’s a lot more negative than positive.

One part of local history I didn’t know about was the Black Mountain Improvement Association. Could you talk about your involvement and how that program helped Black youth in the area?

In the 1990s, I helped lead the Black Improvement Association program for young people in Perry County. In the program, these Black kids learned leadership skills, identity, self-esteem, and received tutoring programs. We did a local governance program, where we took them down to city hall meetings and they learned about how the local government works. They had their own little election where someone was running for mayor, someone running for City Commissioner, and so forth.

It was about teaching self-esteem skills, and really giving them a sense that, “Hey, I can do this, I can do something.” Some of those kids even today after they’ve grown up, they’ll talk about what they learned from that program and how it helped them and how much fun they had. That’s one of the things that the Cultural Center will start—some kind of leadership program for young people.

When it comes to developing our young leaders, nobody else is gonna do it. So we’ve got to do it ourselves. When I was working with ARH, one of their challenges was hiring and retaining certified coders. They didn’t want to come to the mountains to work. They could get twice the pay working in the urban areas, in Lexington and Louisville.

So we built our own. Me and my coworker at that time, we designed an educational program to teach those who wanted to learn how to code. We partnered with the community college so they could get accredited out of that. Those students came out and they went and set for their certification exam, and every last one that I know of passed.

What was it like growing up in Hazard?

I look at myself as an Appalachian and an African American living in Appalachia. And I had some identity issues growing up trying to rectify and reconcile those two identities. I’ve always loved history, and this area is rich in history, African American history: in the settling of the area, how Blacks came to this area. Everything that was mentioned in the BLAC paper is what we’ve experienced in this area also, and is one of the reasons why we wanted to do the Cultural Center.

When I was a kid, we didn’t really think about the beauty of the area, but we enjoyed it. We’d go up and play in the hills where we grew up, me and my brothers. Daddy had a cornfield up there on the hill, and we’d spend the whole day up in the hill. We built forts, we’d go hickory nut hunting, and all kinds of things.

My favorite place to go in Cleveland in the evening was the Ninth Street pier downtown on Lake Erie. Peaceful seagulls, the lake, and the water crashing up against the rocks—all of it somehow reminded me of home. Something about nature. Now I like going for walks. I really love the beauty of nature.

When I was growing up, I was dealing with multiple cultural identities. I wanted to be a country music singer. I even wrote a song. I wrote poetry and sent it to some place in Nashville that converted your poems into songs.

But when I was young I didn’t grow up listening to Black music. We didn’t have a Black radio station here. My daddy he was in the Korean War and he served in Germany. When he came home he brought this big radio—it was one of those in the wooden cases that set on the floor really high up—and it would pick up stations from all over the world. One day I picked up a station. I think it was out of Knoxville called “Randy’s Record Mart.” It was a Black radio station. And that kind of opened up a lot of things.

I remember listening to Michael Jackson, and they played a lot of Motown artists. But then at night, I would go watch Hee Haw. So, there was this clash of cultures.

How has that path away from east Kentucky and then back home shaped what you want to do with the Center?

I graduated from Berea, and from Berea I went to Indianapolis and worked and then I went to Cleveland and I spent about 11 years. I went through a lot of things that I think I had to go through during my tour through those cities before coming back home to do what I needed to do.

I always had this deepest desire to come back home and do something and make a difference, but I did not know how I was going to come back home job-wise. I graduated with a degree in English from Berea, but when I was in Cleveland I went back to Cuyahoga Community College. And it was that move that opened up the door for me to come back home. I eventually became the medical records director at Whitesburg hospital.

How do you see young people shaping the future here, and how do we help them stay?

We lose a lot of our young people nowadays. When they graduate, they have the mindset, “I ain’t never coming back.” I’m hoping that more of those young people—if they do go away—I’m hoping that there’ll be more of them that will have the desire to come back and make a difference in their community. That is one of our goals: trying to retain our young people in the area. And helping get our young people interested in their history because our history is important.

We’ve got to take time to make that investment in their lives, and plant seeds in their lives. They have fresh ideas, and that’s what a lot of our places, our economies, need to be jump-started again. But these young folks still have respect for our traditions and so forth. I think one thing that is key in the changes starting to take place in Hazard is the influx of young adults, who have a lot of new ideals. And they’ve been able to begin to incorporate them, so things will begin to change.

There’s a lot of conversation about transition happening in east Kentucky, and about investments in infrastructure with the new bipartisan infrastructure law. What’s missing from that conversation?

The influx of innovative and creative ideas is good. There’s this “city revitalization” process that’s going on. Most of the towns are, frankly, trying to survive, trying to recover from the coal decline.

The thing that is in the back of my head is they’re doing a lot of work on the buildings and the infrastructure. But one thing that we should never forget is you can restore the buildings, but there’s got to be a movement to revitalize people. You can paint the buildings in the whole town, but if you have the same issues, like homelessness, hunger, and the drug situation, then that doesn’t change the actual situation for people.

We’ve got to be looking at those things too. I know they have in the past and they still are, but we need to bring more people to the table—the right people to the table to help with some of those issues. Then you will have true revitalization.

How do you think our history should inform the efforts to build a new economy here in east Kentucky?

There are some bad parts to that history, but we take that history and own that history and say, “We won’t do this again, we won’t go in that direction again.” But if you try to cover it up and ignore it, and you try to sweep it under the rug like it didn’t exist, you’re prone to make the same mistakes. We’ve got to learn from our history.

There’s this discussion about not wanting to hear that history or see that history because it might make some people feel guilty or like a bad person. I was talking to someone the other day about how my grandfather was chased by the Ku Klux Klan right here in Perry County. And she began to tell how her father was in the Ku Klux Klan. Maybe it was something that she was reluctant to discuss, but that don’t make her a bad person. We need to talk about the history, talk about the things that went on, so that we can understand them. In order to see change, we need to have the conversation about these issues that went on.

We see a lot of the Confederate flags still around the area. We need to have a conversation about that, so that we can come to an understanding and find that common ground. That’s my big thing right now is that word right there, “common ground.” We need to find what we share in common as people living in this region so that we can move forward. I think that if we work at that, and have that conversation, we’ll find that we have more things that we share in common than things that keep us divided.

Because there are things that we do share in common. If you go to the dinner table of an African American family in the area, you’re going to find soup beans, cornbread, and a big chunk of onion like on the table of many Appalachian families.

In other places in the region—like the Triangle Neighborhood in West Virginia in the 1970s or the Georgetown neighborhood in Harlan—infrastructure buildout displaced Black communities. Episodes of our history like those—or the history of the Ku Klux Klan in the area that you noted—have understandably left lingering pain and a lack of trust in Black communities. How do we address that?

I believe from the trauma there has to be a healing. And in order for healing to take place, there needs to be that conversation around whatever caused the wound. I don’t think that conversation has taken place enough in the past. Reconciliation is going to be a key thing, and you have to have the right people at the table to have that conversation. If you don’t, then you might as well be talking to yourself.

I think that’s one of the things that I personally am called to do: to be an agent of reconciliation. And to bring back together around that common ground. At the Cultural Center that’ll be one of our primary focuses.

What advice would you give to leaders in the area in bringing the right folks to the table?

Well, number one, you look and see who’s already sitting at the table. And usually for every conversation, it’s the same people sitting at the table. You’ve got to invite those who are really affected by whatever it is you’re dealing with–those who are going through it.

For example, I really want to look at the whole issue of homelessness in our area. And often we don’t think about who do we bring to the table to talk about that. If someone is homeless, I want to hear their story, how they got to be in this position that they are in today. And what it means to them to be without shelter and how it affects meeting their basic needs. I’d make sure that they are at the table because it’s important to have those who are affected and dealing with the issue as a voice at the table.

I understand that the Cultural Center has projects around the art and history of quilting, around preserving Black cemeteries in the area, and gathering histories about local Black churches. Why do you think these projects are important?

We’re doing multiple projects right now. One is called “Stories Behind the Quilt.” Quilting is a part of Appalachian culture, and is part of African American culture, so we’re doing this project to get these stories, and we’re looking at it as a dying art. I’m looking for African American quilters. I want to get their stories, take pictures of the quilts, and then have some intergenerational workshops with the participants actually setting around making a quilt. Each person will contribute a block, and it’s going to be something about their history or it’s going to mean something. And we’re going to share those stories around the quilt.

My mom’s made a lot of quilts [for example]. And there’s one in particular that she has. It’s called a “moon beam” quilt that she made when they sent the Apollo mission to the moon and walked on the moon—it’s in remembrance of that. Another woman I’ve been talking with has a quilt that was made by ancestors during slavery times. It was on exhibit at one point at the Smithsonian, and we’re arranging for her to bring that. Hopefully [this project] will perk up the interest of our young people to say, “hey, I want to learn how to make a quilt, I want to learn how to do this.”

Another project that we’re working on is we’re going to visit all the cemeteries where Blacks are buried and create some kind of a registry. We’re working in this one cemetery right now—Englewood—it was a segregated cemetery. And of course, the section where the Blacks are buried was not kept up. There are some names on them that you can read. There’s some that you can’t read. But we want to find those.

I’ve heard there are over 300 grave sites in Perry County. That doesn’t mean that Blacks are buried in all those cemeteries, but we mostly know where the Blacks are buried. There is an all-Black cemetery over on Town Mountain. We found out that there is a Black cemetery in Leslie County. I don’t know if it’s being kept up, but I want to get over there and begin to record names and so forth.

We’ll have it so when someone goes on our website, they can click on a person’s name and it will show their information—just like Find A Grave, but it’s gonna be ours. Once we get those names, then we can begin to search genealogically and try to get information on these folks. History speaks even from the grave. We’ll be capturing the stories of those folks that’s long forgotten.

A third project that we’re working on is with churches in the African American tradition. I was talking to a pastor in Fleming-Neon and McRoberts [in Letcher County], and he was telling me about all the Black churches that used to be there. There’s several that’s closed, but he’s pastoring a couple up there. When you think about that, as the population gets older and the young folks leave, before you know it there will be no physical evidence that Blacks lived there. We want to talk to all those churches that’s here [in the area]—it’s important to get their stories, their history, before that happens.

How can people support the Cultural Center?

Those who have artifacts—especially old pictures from this area—can support by contacting us about them and letting us become caretakers of the artifacts.

People can support financially by making a donation. We’ll need that support. That’s one of our challenges is to make it sustainable because I want it to be something that’s around long after I’m gone. I see the Cultural Center as an agent of change. It’s a gathering place. We just want to be that organization, that whatever’s needed in the community, we want to be there to have some kind of impact on whatever that endeavor is. Whatever we can get our hands into to bring about a change.

[Some of Hudson’s essays and poetry can be found here and here.]