Ohio’s state parks, forests, and wildlife areas are being queued for fracking development thanks to an opaque new law infamously dubbed the “poultry bill.” House Bill 507 started as an agricultural bill before it was amended behind closed doors—under the influence of the oil and gas industry—to require oil and gas leasing on state-owned land.

Concerned residents and community groups have raised alarms about the law’s public health and environmental consequences, its blatant handouts to oil and gas corporations and wealthy households, and its lack of public transparency. And recent polling data suggests these concerns are far from uncommon—though elected officials and the oil and gas industry may be bullish on new gas leases, the public itself is skeptical.

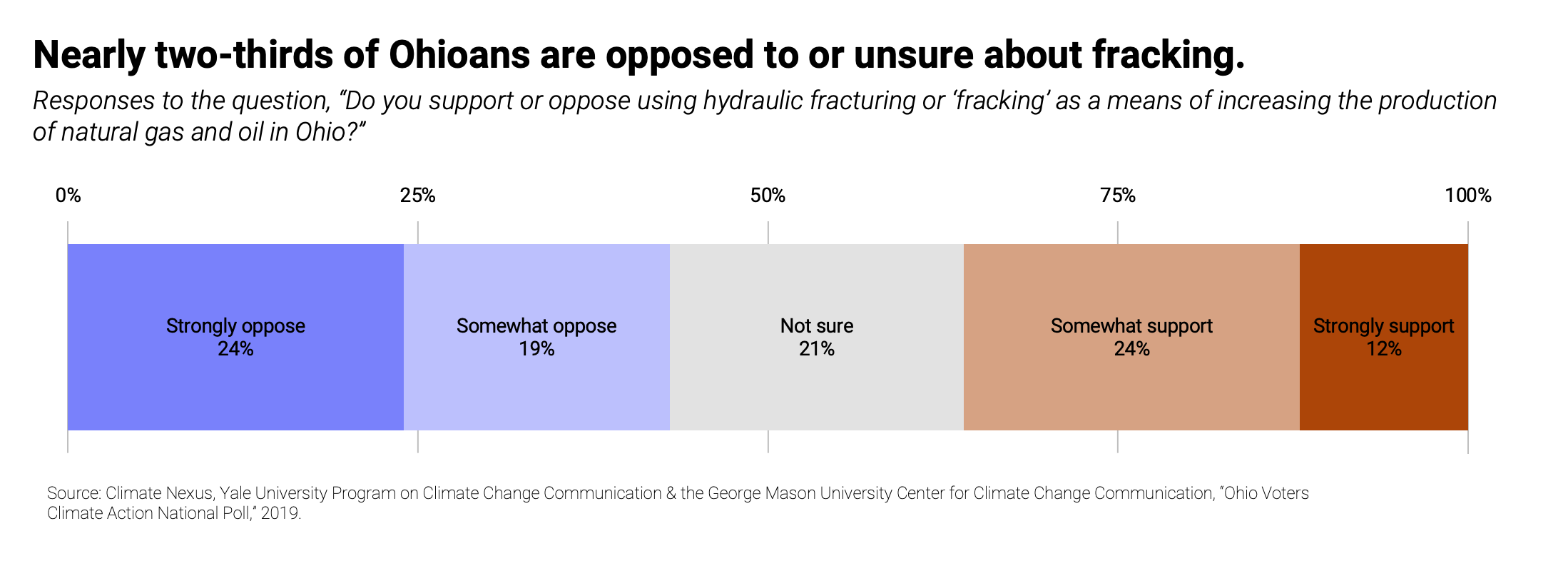

Most Ohioans are either opposed to or unsure about fracking, according to a pair of public opinion surveys. Baldwin Wallace University’s 2022 Ohio Pulse Poll and a 2019 poll from Climate Nexus, the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, and the George Mason University University Center for Climate Change Communication show majorities (53.7% and 64%, respectively) of Ohio voters say they are either strongly opposed, somewhat opposed, or unsure about hydraulic fracturing as a means of increasing the production of natural gas in Ohio. And, when asked about their best guess on other voters’ perspectives, George Mason University/Climate Nexus respondents said more Ohioans generally oppose (38%) than support (33%) fracking in the state.

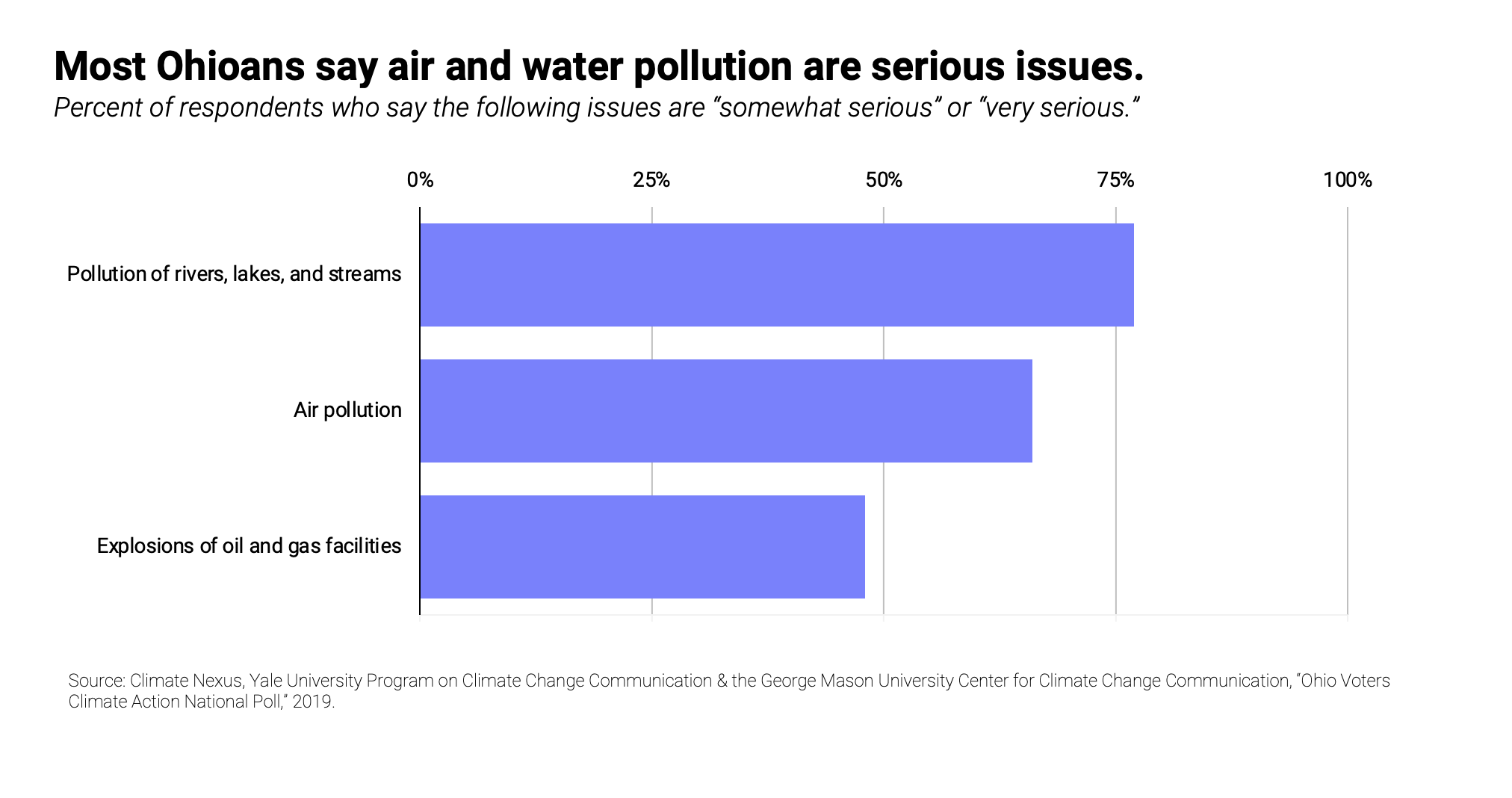

There’s clear dissonance between the state’s political agenda and the concerns of its residents. While proponents of state park leasing point to prospective revenue, Ohioans share broad and resolute concern about the documented threats of fracking, like air and water pollution and rampant carbon emissions that worsen climate change. Overwhelming majorities of Ohio voters say air pollution (66%) and the pollution of the state’s rivers, lakes, and streams (77%) are “very serious” or “somewhat serious” problems. Nearly two-thirds (64%) say they are worried about climate change and its effects.

As advocates have pointed out, these environmental and health risks take on particular resonance when the state’s public lands—parks, forests, and wildlife areas shared and enjoyed by millions—are in the crosshairs. These areas provide a refuge for recreation, sport, leisure, and community, and an economically important one, at that. Ohio’s outdoor recreation sector added a value of over $8.1 billion to the state income and employed nearly 133,000 workers in 2017, according to an Ohio State University study. In large part, this sector relies on clean air, fresh water, and the sanctity of the natural environment—precious, fragile commodities that can’t be guaranteed once fracking is underfoot.

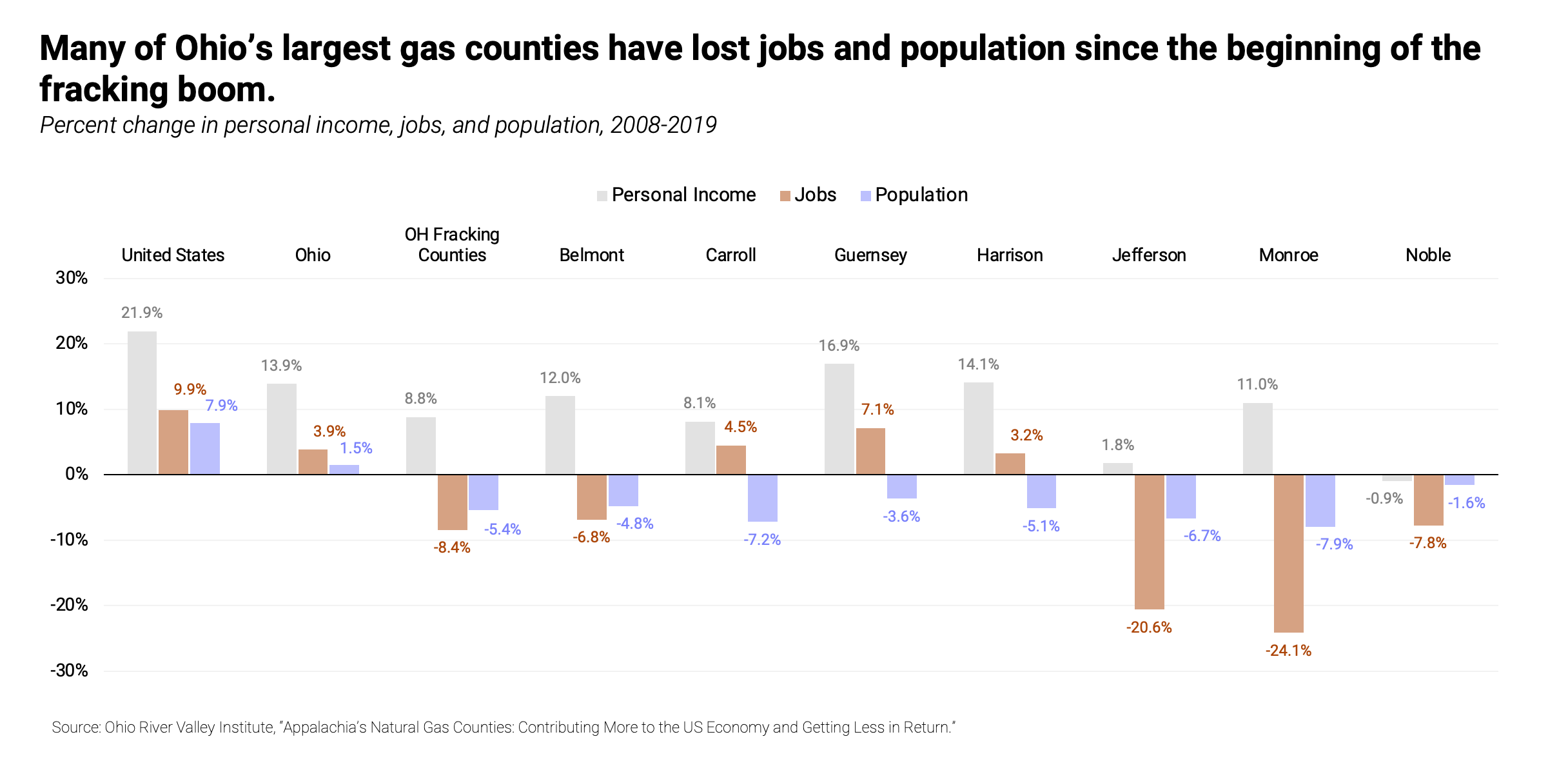

Still, politicians and industry boosters claim the economic benefits of leasing state lands will outweigh the costs. History suggests otherwise. In Ohio, nearly a decade and a half of fracking has failed to generate local economic growth in the state’s largest natural gas counties, data show. From 2008 to 2019, the seven counties that account for about 95% of the state’s natural gas output did generate enormous GDP growth—88.7%, more than quadruple the GDP change of the state and the nation. But that booming output failed to translate into prosperity for Ohio’s fracking counties—in fact, it corresponded with a hollowing out of local economies. In the same period, those counties lost 8.4% of their jobs and 5.4% of their populations, a decline of 13,795 residents. Personal income growth (8.8%) lagged far behind state (13.9%) and national (21.9%) averages. For Ohioans, the story of the fracking boom has been one of depopulation and economic decline.

Precedent suggests fracking state lands won’t create job growth, it won’t boost incomes, and it almost certainly won’t grow the nearby population. Will it generate revenue? That’s another argument legislators and industry representatives have leaned on to justify new leasing. But, as Guillermo Bervejillo of Policy Matters Ohio pointed out to the Ohio Capital Journal, Ohio’s severance tax rate is one of the lowest in the nation, meaning new drilling won’t yield much for the state’s coffers:

Ohio’s severance taxes are pitiful, and they have meant a severe missed opportunity for Appalachia and for Ohio as a whole. Ohio drilling operators pay a dime per barrel of crude oil and half a nickel per thousand cubic feet of natural gas. This is one of the lowest severance taxes in the country and it means that years of gas and oil production have enriched corporations and drillers but not the communities that host them nor the state that supports them.

Low severance taxes have cost Ohio enormous amounts of revenue, Berjillo’s research suggests. Since 2010, more than $40 billion worth of natural gas has been fracked from Ohio’s shale deposits. Berjillo explains that, from 2016 to 2021, Ohio could have garnered more than $1.5 billion in revenue with a flat 5% severance tax rate on crude oil and natural gas extraction, a figure proposed by Policy Matters Ohio over a decade ago. That’s $1.24 billion more than the state actually collected in that period, according to Ohio Department of Natural Resources data.

If the question is how to generate genuine economic growth and meaningful state revenue, more fracking is not the answer. Research shows that investing in clean energy and energy efficiency upgrades is much more effective than fossil fuel expansion at creating lasting job growth and local economic prosperity, even in areas—like Ohio’s natural gas region—that have endured long-term economic decline.

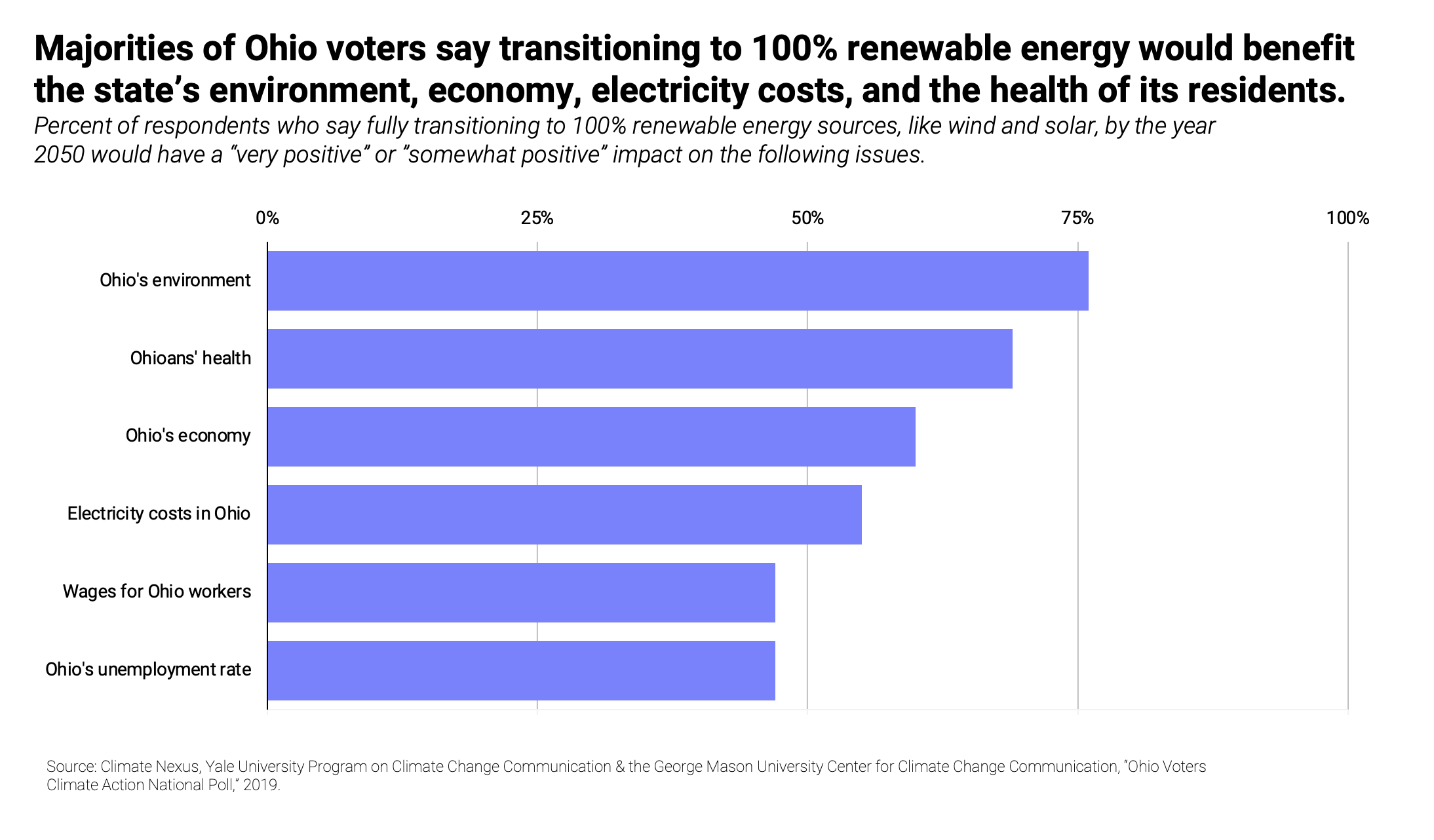

And in Ohio, support for these types of investments is abundant. When asked about the most important priority for addressing Ohio’s energy needs, nearly two-thirds (63%) pointed to developing more renewable energy resources, such as wind and solar, according to the George Mason University/Climate Nexus poll. Voters agree that transitioning to renewable energy would have a positive impact on public health (69%), the environment (76%), the economy (60%), and electricity costs (55%). And a majority (53%) of Ohioans say increasing domestic production of renewable energy is more likely to produce a greater number of good jobs in the state than increasing domestic production of fossil fuels, like natural gas.

The voice of the people is clear. Ohioans are skeptical of the fracking industry and the need for more drilling, even as industry-led decisionmakers push to expand leasing to beloved—and economically fruitful—state parks, forests, and wildlife areas. Time will tell if Ohio’s leadership decides to heed public will.