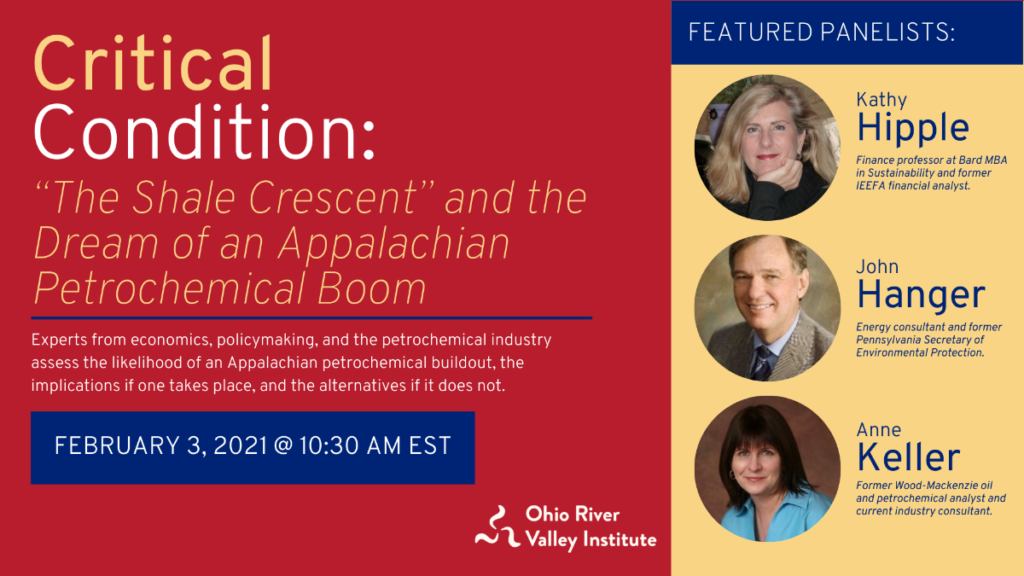

On February 3rd, 2021, the Ohio River Valley Institute convened a forum of experts from finance, policymaking, and the petrochemical industry to assess the future prospects for the creation of a petrochemical hub in the greater Ohio Valley. View a recording of the forum here.

The Shale Crescent Vision

For more than a decade, policymakers in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia have constructed economic development strategies around the expectation that abundant supplies of natural gas could fuel a massive expansion of energy and manufacturing, spurring employment and prosperity across Appalachia. A 2010 American Petroleum Institute report anticipated the shale gas boom would create hundreds of thousands of jobs in the Marcellus Shale region. But according to the latest research from the Ohio River Valley Institute, very few jobs materialized, even though production exceeded analysts’ expectations. Between 2008 and 2019, gross domestic product (GDP) in the 22 major natural-gas-producing counties in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia grew at three times the rate of the U.S. economy, but the region’s share of the nation’s income, jobs, and population all declined.

Then, about five years ago, the oil and gas industry unveiled a new campaign claiming that Appalachia’s bountiful natural gas reserves could lead to a massive expansion of the region’s petrochemical and plastics manufacturing sectors, generating more than 100,000 new jobs in the process. A 2017 American Chemistry Council (ACC) report, widely trumpeted by regional policymakers, the Department of Energy, and the Trump Administration, sketched out plans for an Appalachian petrochemical buildout that could allegedly rival the scale of the petrochemical industry along the Gulf Coast. The report foresaw the construction of five world-class ethane crackers, two hydrogenation plants, and an Appalachian Storage Hub connected by 500 miles of pipelines.

Four years later, both global markets and policy responses to climate change have thrown into doubt the viability of the Appalachian petrochemical dream. Development of major petrochemical facilities in the region stalled well before the onset of the coronavirus crisis, and just one of the nine infrastructure projects outlined in the ACC study has received the green light. Three others have been cancelled outright, and both the Appalachian Storage Hub and an ethane cracker proposed for construction in Ohio’s Belmont County remain in limbo.

After years of failed promises, is it time to wake up from the Shale Crescent dream?

The experts assembled for the Ohio River Valley Institute’s inaugural forum cited stiff market headwinds, excess ethylene and polyethylene capacity, and threats to fossil fuel and plastics demand as reasons why the envisioned Appalachian buildout is unlikely to go forward.

Panelist Kathy Hipple, Professor of Finance at Bard College’s MBA in Sustainability program and a former financial analyst for the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, pointed to imposing financial hurdles faced by the fossil fuel industry, which has struggled to turn profits since the beginning of the natural gas boom.

“It is important to remember that the petrochemical industry is part of the broader oil and gas industry that has been experiencing global problems. Many of these companies have slashed their capital expenditure by fully 50%. They don’t have as much cash as they used to,” Hipple explained.

“Locally, they’re producing gas, but they haven’t yet been able to make it a profitable business. You’ve got an industry in distress looking for salvation, hoping that the petrochemical build-out in Appalachia might be that lifeline. The financials do not support that contention.”

Anne Keller, a former Wood-Mackenzie petrochemical analyst and current industry consultant, added that the likelihood of an Appalachian petrochemical buildout has been narrowed by infrastructure development along the Gulf Coast. Conducive terrain, low labor costs, and the presence of existing oil and gas infrastructure, such as pipeline grids and ample above-ground storage capacity, eased the cost of development in the Gulf Coast area. Constructing petrochemical infrastructure in Appalachia has proven considerably more difficult and expensive. “The gas in the Marcellus Shale region also has a higher percentage of ethane,” Keller noted, “With this much ethane, they will not be able to put all of it into pipelines because of residential delivery specifications.”

The panelists acknowledged that the Shell ethane cracker in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, is likely to be constructed, although Hipple questions its ability to live up to forecasted employment expectations. However, the prospects of the repeatedly-delayed PTT Global Chemical America (PTTGCA) cracker proposed for construction in Ohio’s Belmont County are growing increasingly doubtful. PTT Global Chemical, the Thai parent company in charge of the cracker’s development, is again indefinitely postponing a final investment decision as it “needs more time to adjust its cost and form new business partnerships.”

According to Hipple, “the economics do not make sense, which is why PTTGCA has not gone forward.”

The panelists also did not foresee the financial hurdles faced by PTTGCA and other regional petrochemical projects subsiding after the pandemic. They cited the threat of falling demand for virgin plastics, driven by public concern over the plastics pollution crisis and climate change.

Keller cited two formative shifts in the plastics market since the release of the 2017 American Chemistry Council study. First, consumers’ skepticism of single-use plastic products is shaping corporate behavior at the highest levels. Fearful of “losing their social license to operate,” an influential cohort of packaged goods companies, including Nestle, PepsiCo, and Procter & Gamble, are requiring that at least 75% of packaging material be recycled or biodegradable by 2025. Second, China’s 2018 decision to stop importing plastic waste and recycled materials has rattled the global petrochemical market.

“Those two things were a huge stop,” Keller said. “They changed the growth assumption of the entire plastics industry.”

With market forces casting dark shadows over the viability of an Appalachian plastics hub, policymakers’ insistence on large-scale petrochemical investment appears misplaced. But without fossil fuels to rely on, what economic opportunities remain for the Ohio River Valley region?

According to panelist John Hanger, an energy consultant and the former Secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, policymakers and economic development councils need to focus “on the facts” rather than “motivated thinking.”

“The number of infrastructure projects that have been canceled far exceeds the one Shell cracker plant that is now under construction,” he said. The region “ought to build on its strengths in education and health care” and redirect funding to investments in burgeoning green technology. Even fossil fuel companies are beginning to shift focus from oil and gas to renewables, Hanger noted.

“If you look at the majors in the European oil and gas industry, like BP, Total and Equinor, they’re all moving into clean tech of one sort or another, making investments in electric charging networks, offshore wind, and solar. This is not the Sierra Club — it’s oil and gas companies,” he said.

Hipple agreed. “It’s difficult to sit on a natural resource and not think it’s a ticket to economic development,” she said, “but it’s important to step back and take a cold hard look at the realities of the economics. Simply put, the natural gas industry has not delivered the promised benefits for producers, investors—or local communities.”