At ORVI, we’ve documented the inability of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industries to serve as engines for job growth and prosperity in Appalachia. Although these findings may be greeted with doubt, disbelief, and sometimes anger, we find that, once the numbers sink in and people in the mining and fracking regions of Pennsylvania and the Ohio Valley look around at their communities — the struggling downtowns, declining populations, and the departures of their sons and daughters to places far away in search of opportunity — reality usually takes hold.

It can be a profoundly sad moment. But, for local leaders who may have invested years promoting these industries as economic saviors, the realization can be bitter and give rise to a question that is equal parts a challenge and a plea — What’s the alternative?

When you’re on the receiving end of that question, you feel its weight. And, if you don’t have an answer, you can feel that you’re stealing someone’s — maybe an entire community’s — hope and you’re leaving them with nothing.

Confronting the question in Moundsville, where a possible power plant retirement looms

I was faced with the challenge of answering that question a few weeks ago when I was asked to provide testimony to the West Virginia Public Service Commission (PSC) concerning the economic impacts of a possible 2028 retirement of the Mitchell coal-fired power plant located just south of Moundsville.

Even before the onset of the pandemic, Mitchell was operating at only about 37% of capacity due to competition from lower cost natural gas power plants that have popped up in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Its continued operation and that of many other remaining coal-fired power plants can no longer be justified economically, which is why West Virginia’s heavily coal-dependent energy system has saddled the state’s customers with the nation’s fastest rising electric bills over the last decade.

Still, in 2019 Mitchell employed 185 people full-time in high-paying jobs and, according to a recent analysis by WVU’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research, the plant’s multiplier effect in West Virginia’s economy means that it supports 661 total jobs. That’s in part due to the fact that the plant locally sources 90% of the coal it burns from mines in Marshall and Ohio Counties. Mitchell also pays about $6 million annually in property taxes to Marshall County and $16 million in business and occupation taxes to the state.

In short, Mitchell matters economically and the possibility of retirement has united the West Virginia Coal Association, the state attorney general’s office, the Marshall County Commission, and numerous other groups in arguing that it should remain in operation. And the challenges posed by a potential retirement of Mitchell are reflective of a problem that haunts thirty-some odd communities in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, where coal-fired plants are being rendered obsolete and are also in danger of closing within the next few years.

So, what’s the solution? Or, more precisely and in the words of assorted local policymakers, what is the alternative for communities whose economies have been in decline for decades, whose populations are falling, for whom the fracking boom has failed to turn things around, and that are desperately trying to cling to whatever remaining sources of jobs they have?

Folks in progressive policy circles talk about “just transition” for places that find themselves in this situation; they talk about clean energy jobs replacing fossil-fuel jobs and worker retraining. But try telling that to workers in their fifties who don’t see any wind turbines or solar farms popping up anywhere nearby and who, when told about retraining, sensibly ask, “What jobs are there here that I can retrain for?”.

An answer to, “What’s the Alternative?”

Here is the answer I gave in my West Virginia PSC testimony. A decade ago, the town of Centralia, Washington was in many respects like Moundsville is today. The town and the surrounding county had a population of about 80,000, which is slightly less than the combined populations of Marshall, Ohio, and Wetzel Counties in West Virginia — the places from which Mitchell draws its workforce.

Centralia is also home to a coal-fired power plant of about the same size as Mitchell and it used to be home to a coal mine that supplied the power plant. However, the mine, which employed 600 people and was the town’s largest private employer, closed in 2006. And in 2011 it was announced that the power plant would shut down as well in 2025, taking with it another 300+ jobs.

It was a hell of a blow for a place that was struggling economically anyway. The mine closure meant that in 2007 and 2008, while the rest of the U.S. economy was growing, Centralia experienced a significant loss of jobs. Then, the Great Recession hit, and Centralia suffered additional job loss. Centralia’s unemployment rate was also worse than the unemployment rate in Marshall, Ohio, and Wetzel Counties even before all of this began. In short, by many measures, Centralia was in even worse economic shape than Moundsville.

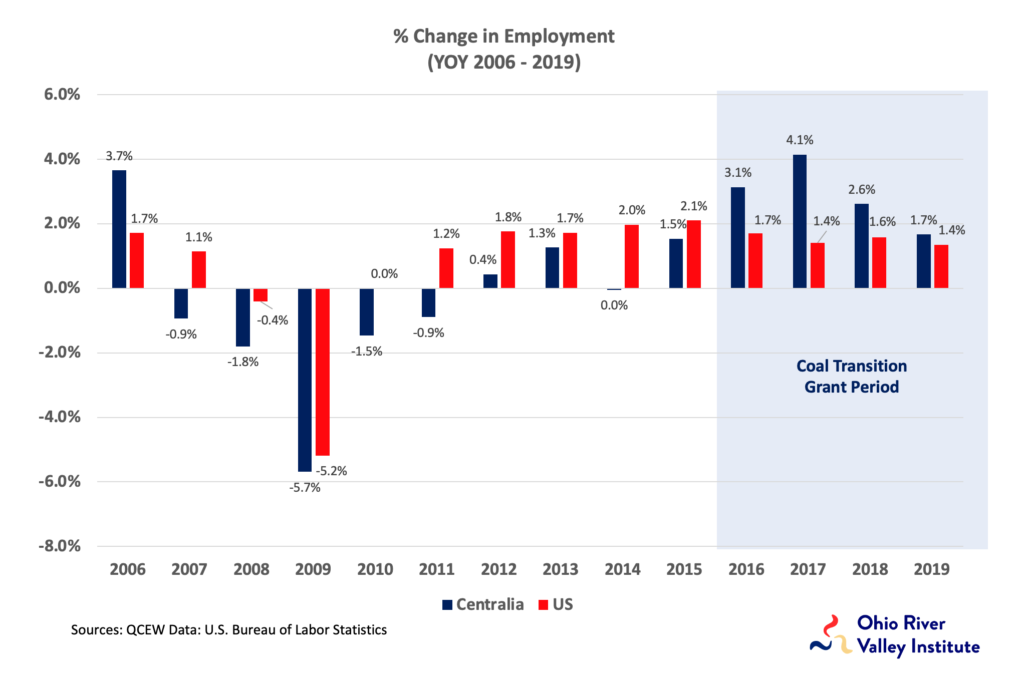

Then something happened. In 2016, Centralia’s rate of job growth surpassed that of the nation for the first time in a decade . . . and kept on surpassing it.

As part of its 2011 plant closure agreement signed with the Washington Governor’s office and assorted energy and environmental advocacy organizations, TransAlta Corporation, the owner of the Centralia power plant, started contributing what will eventually add up to $55 million to a coal transition fund that consists of three component funds:

- A “Weatherization Fund” that supports energy efficiency upgrades for low and moderate-income residents

- An “Economic & Community Development Fund” that supports workers, families, businesses, and organizations to expand education, retraining, and general economic development

- An “Energy Technology Fund” that supports clean energy generation, energy efficiency, storage, and transportation electrification

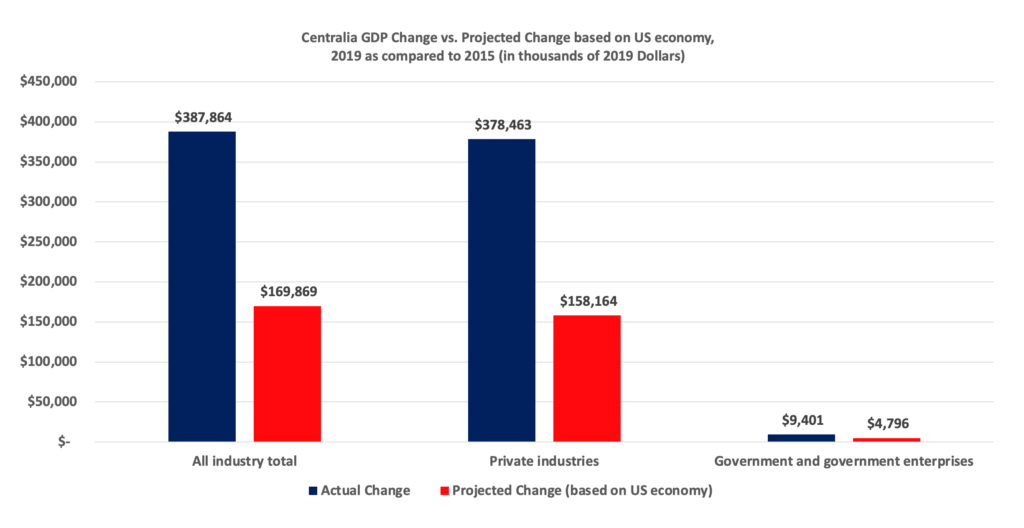

In 2016, the board that administers the funds began making grants and something remarkable happened. Between 2015, just before the grant activity began, and 2019:

- Centralia’s economic output as measured by gross domestic product grew at twice the rate of US GDP

- Job growth boomed

- And the town’s and the surrounding area’s populations grew faster than the national average as well

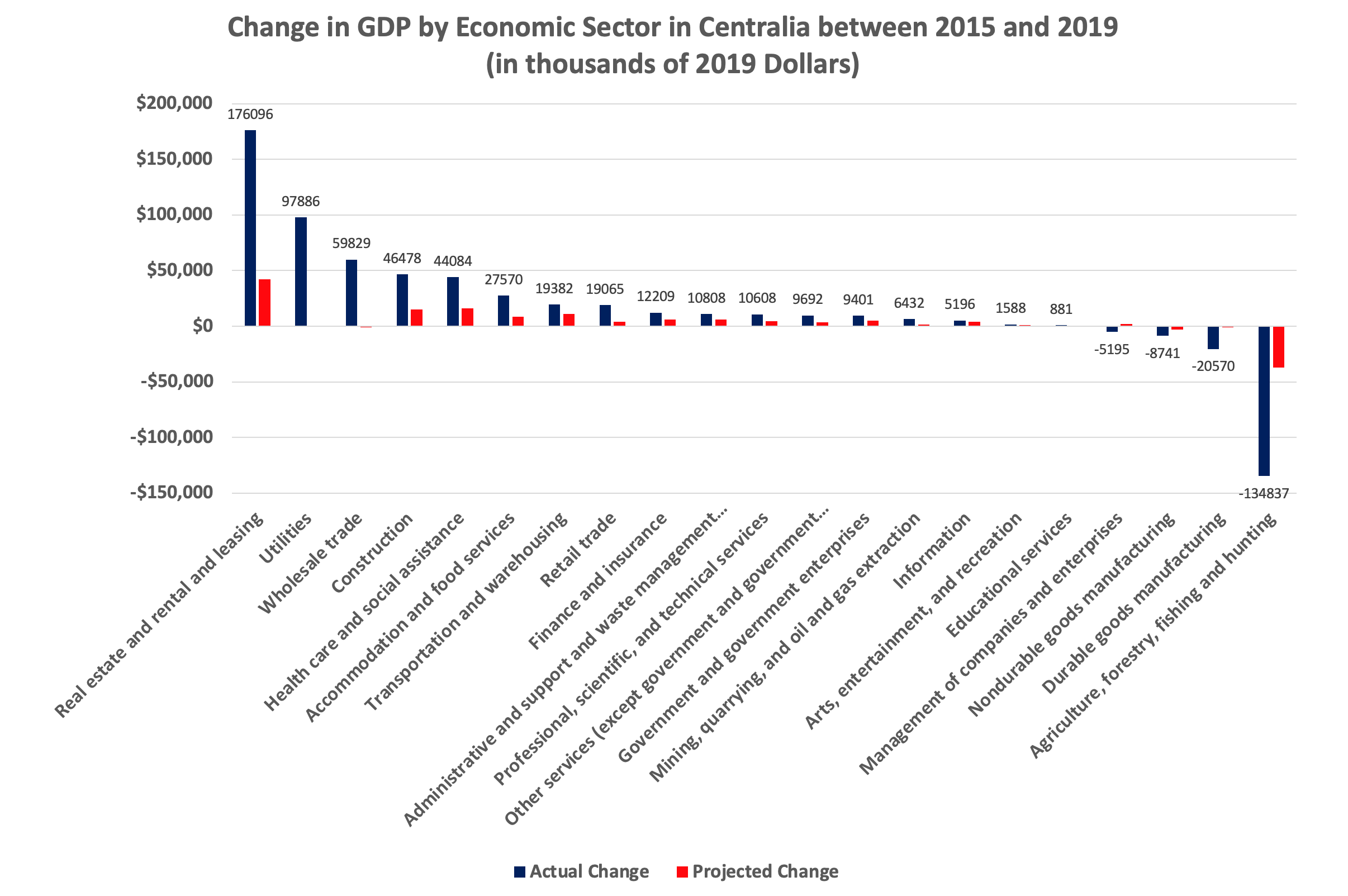

From research, we can identify some of the possible reasons for this striking turnaround in Centralia’s economic fortunes.

- The energy, energy efficiency, and education areas in which the Centralia board is issuing grants are highly labor-intensive, creating 2-3 times as many jobs per dollar produced as is the case for utilities and coal extraction.

- Work in these industries tends to be performed by local suppliers—HVAC, door and window, lighting, and insulating contractors, among others—so, unlike with natural gas investment, most of the suppliers and workforce are local, keeping money and the economic impacts in the local community.

- The grants program is highly efficient because it leverages existing business and programs rather than diverting lots of money to one-time set-up costs.

- The grants are annuity-producing because they lower monthly utility bills, which becomes added disposable income for residents, and they reduce the need for investment in expensive new power plants, which saves even more money.

Finally, the energy efficiency upgrades being made in Centralia result in changes that have been shown elsewhere to produce safer, more comfortable living and workspaces that reduce absenteeism and healthcare costs and enhance the quality of life.

So, even without the arrival of any single major new employer, Centralia is experiencing “bottom-up” or organic economic growth that outpaced the nation in 17 of 21 economic sectors. Between 2016 and 2019, the boom resulted in the addition of 2,885 jobs — a 12% increase and nearly three times the number of jobs that will have been lost as a result of the combined mine and power plant closures.

What the Centralia case means

This video tells a bit of the story about how the transition came about in Centralia.

It must be noted that we can’t yet conclude quantitatively that the coal transition program is the sole or even the principal driver of Centralia’s turn-around. And effective transition strategies necessarily require input and buy-in from the communities and local stakeholders. But, because there are known economic factors that help explain what is happening in Centralia, there are many reasons to believe that the strategy adopted there may serve as a model for Marshall, Ohio, and Wetzel Counties in the event the Mitchell plant is retired. And it may do so in other similarly challenged Appalachian communities as well.

That hope is bolstered by the fact that clean energy, energy efficiency, and retraining and education, the areas of economic transition investment that have proven so productive in Centralia, are also ones that are being prioritized for the investment of federal dollars by the Biden administration in its recent proposals to Congress. And, on top of that, the Biden administration recently identified the communities around the nation most vulnerable to negative impacts from the energy transition and in need of assistance. The Wheeling Metropolitan Statistical area, which includes Marshall, Ohio, and Wetzel Counties in West Virginia as well as Belmont County, Ohio, sits at #3 on the list, which should augur well for financial assistance on top of that which might be provided under a retirement agreement by American Electric Power, the Mitchell plant’s owner.

I should also add that this hopeful message hasn’t yet made mention of additional economic development opportunities associated with the potential remediation of abandoned mines and wells, which are being explored by my ORVI colleagues, and potential opportunities in emerging industries such as plastics recycling and a truly green hydrogen economy.

There is more than can be said and much more to be studied, but it is clear that answers are being found to the fraught question, “What’s the alternative?” And we’ll continue to look for more.

What’s next?

The Centralia case and its applicability to economic development and energy transition in Appalachia will be an integral part of an upcoming report, which will explore the reasons why the natural gas boom failed to trigger significant growth in jobs, income, and population. It will also look at what can be done differently both to get a better deal from the natural gas industry, which for better or worse is a major presence in the region, and to identify alternative approaches to economic development that hopefully will produce more outcomes like the one in Centralia.

Look for that report by the end of June.