January 25, 2022 may become the day the music died for a number of the remaining Appalachian coal-fired power plants.

That’s when PJM, the regional transmission operator (RTO) that manages wholesale energy markets in all or parts of 13 mid-Atlantic and midwestern states and the District of Columbia, will hold a “capacity auction” to lock in enough electricity generating capacity to ensure the reliability of the region’s electric grid from 2023 to 2024.

Power plants and other providers of energy services that offer to make their capacity available at the lowest prices become eligible for capacity payments from PJM based on how much electricity they are capable of delivering. The value of the payments is significant. This year, PJM is paying suppliers that cleared the latest capacity auction $140/MW-day (megawatt day). For a 1,500 MW power plant, which is typical for major coal-fired plants in the area, that comes to over $75 million a year, sometimes more than a quarter of all the revenue a power plant earns. That’s because the money plants receive in capacity payments is over and above the money they make from generating and selling electricity.

At a time when many coal plants are experiencing declining capacity factors (utilization rates) and corresponding losses in sales and market share due to intense competition from low-cost natural gas and renewable resources, capacity payments can be financial life savers. But, if the value of capacity payments were to drop precipitously, some plants could suddenly find themselves no longer financially viable. That’s just what happened in June, when the PJM auction for the year 2022-2023 came in with a price of just $50/MW-day, down from the previous price of $140/MW-day.

The drop represented a 64% decline in capacity payment revenue for the plants that successfully cleared the auction. And it represented a 100% decline for those that failed to clear the auction because their bids were too high. Consequences were immediate. A month after the auction, Vistra Energy announced that the 1,351 MW Zimmer coal-fired power plant in Clermont, Ohio would be retired in 2022, five years ahead of schedule. Four months later, First Energy announced that the immense 2,220 MW Sammis plant in Stratton, Ohio, which had previously retired four of its generating units, would retire the remaining three in 2028.

Now, remaining coal-fired plants that are financially vulnerable are facing another run through the gauntlet. On January 25th, PJM will hold its 2023-2024 capacity auction. If that auction produces a similarly low capacity price, additional plants could go down. And we don’t have to look far to find candidates.

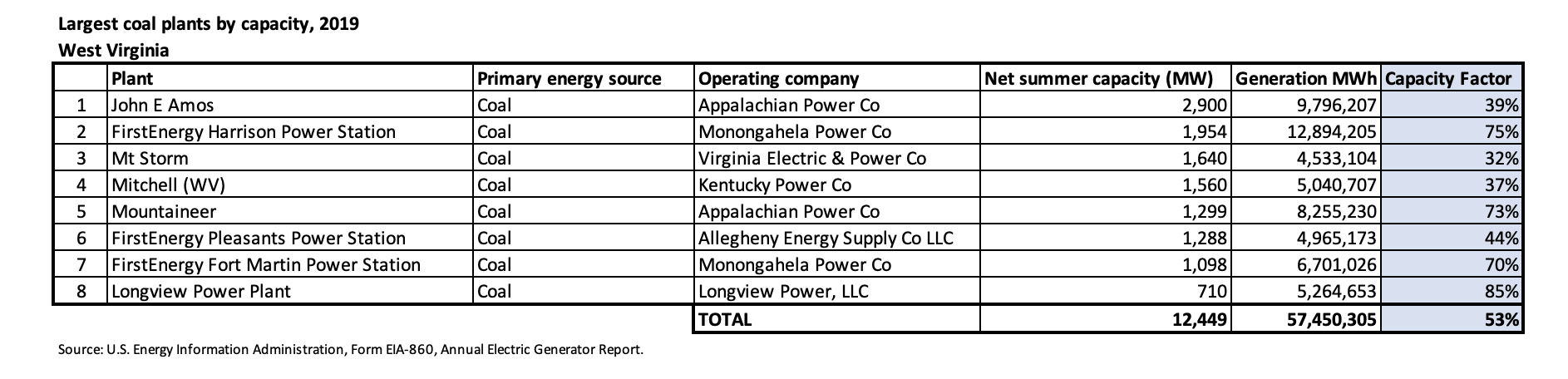

For confidentiality reasons, PJM does not disclose which plants receive capacity payments, but we know from public records that many coal plants are operating at historically low levels. In 2019, before the pandemic, four of West Virginia’s eight major coal plants were operating at less than 50% of capacity and 3 were operating at less than 40%, including the state’s largest plant, John E. Amos in Putnam county, and the 1,560 MW Mitchell plant in Marshall County. A number of plants in Pennsylvania are also rumored to be on very shaky financial footing.

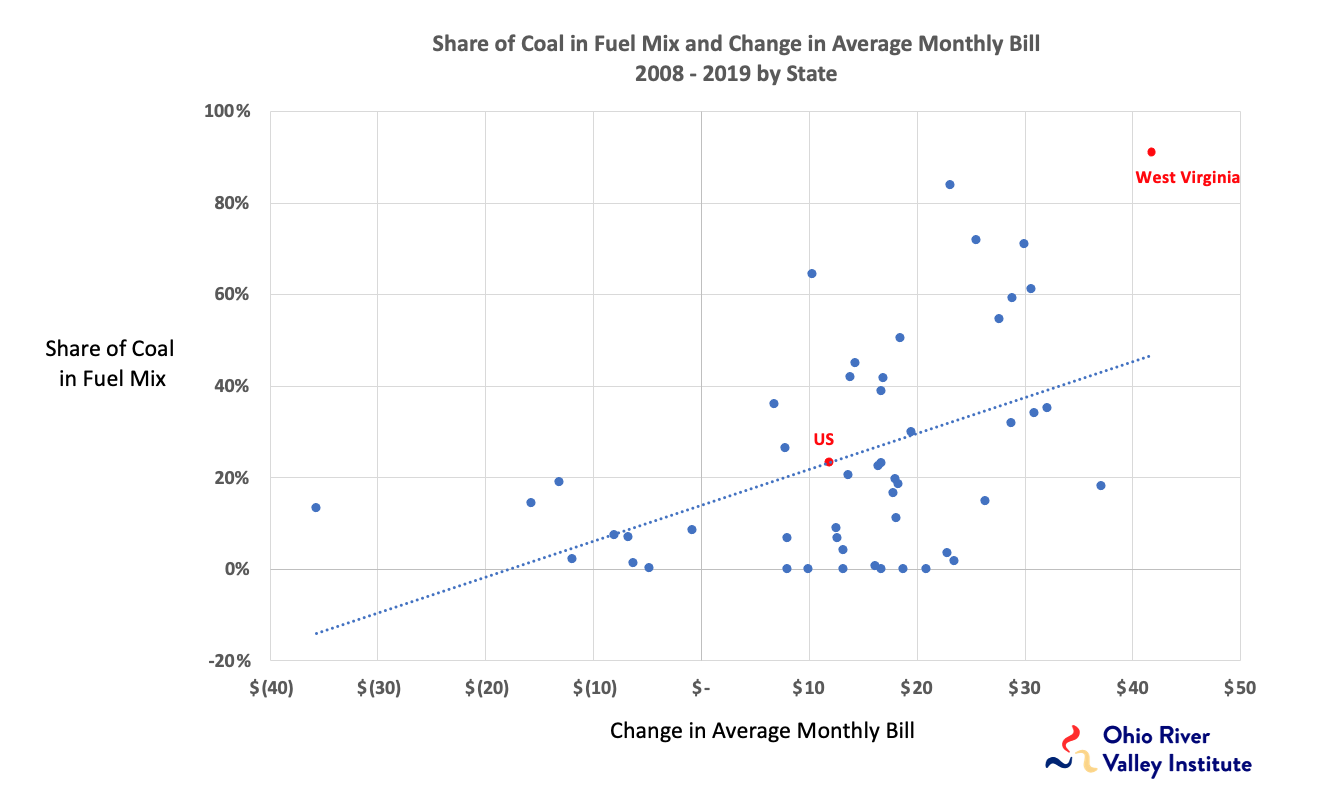

Some inefficient coal plants find shelter because they are partially insulated from market forces, In regulated states like West Virginia, utilities are allowed and sometimes encouraged by state public service commissions to shift operating costs that they can’t recover from sales of electricity into the wholesale market onto the backs of West Virginia customers.  That’s a large part of the reason why, between 2008 and 2019, customers in West Virginia were hit with the fastest rising electric bills in the nation and states whose electric systems are most reliant on coal experienced many of the biggest increases.

That’s a large part of the reason why, between 2008 and 2019, customers in West Virginia were hit with the fastest rising electric bills in the nation and states whose electric systems are most reliant on coal experienced many of the biggest increases.

At some point, however, the capacity of customers to absorb rate increases will be exhausted, in some places sooner than others, and market forces will prevail. The upcoming PJM 2023-2024 capacity auction could induce a final reckoning sooner than many communities that host vulnerable power plants are prepared for. Or it could produce a price correction in response to the last auction’s stunning result. Either way, it’s an event to which some of us will be paying attention in breathless anticipation.