Four years ago, petrochemical industry boosters predicted a new wave of industry would roll across the natural gas-producing region of Appalachia, spurring billions of dollars in capital investments and a veritable economic renaissance in a place that sorely needed it. A 2017 American Chemistry Council study claimed that the region’s bountiful shale reserves could fuel a massive petrochemical and plastics manufacturing expansion to rival the scale of the petrochemical corridor along the Gulf Coast. Five world-class ethane crackers, two hydrogenation plants, and an Appalachian Storage Hub connected by a 500-mile network of pipelines would process ethane from fracked gas into plastic micropellets, the building blocks of single-use plastic products, creating more than 100,000 new jobs in the process.

But the forecasted petrochemical boom never took hold. Only one of the five ethane cracker plants once planned for the region ever moved beyond a final investment decision, and the industry’s imagined storage hubs and supplemental pipeline network are still stuck on the drawing board.

Now, new research from the Ohio River Valley Institute suggests the petrochemical dream may never come to fruition. The report surveys the financial outlook of future Appalachian petrochemical development, concluding that new capacity additions are unlikely to move forward.

“Poor Economics for Virgin Plastics: Petrochemicals Will Not Provide Sustainable Business Opportunities in Appalachia” explains that the Appalachian petrochemical dream traces its roots back to the region’s fracking boom, which began in earnest more than a decade ago as drilling rigs and other fracking infrastructure swept across the Marcellus and Utica Shales underlying Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Rampant fracking quickly created a natural gas supply glut, causing prices to decline precipitously. The industry’s profit margins have suffered accordingly. For a decade, Appalachian fracking companies have consistently posted negative free cash flows, sinking billions of dollars into the construction of new drilling rigs, processing stations, and other infrastructure. Major oil and gas corporations are fleeing the region, offloading capacity for “pennies on the dollar.” More than a dozen regional producers have filed for bankruptcy. Even with a recent uptick in natural gas prices, the long-term outlook for shale gas producers looks dim.

Shaken by long-term financial duress, fossil fuel companies have searched desperately for a new business model. Many are now pinning their long-term fortune on plastics and petrochemicals.

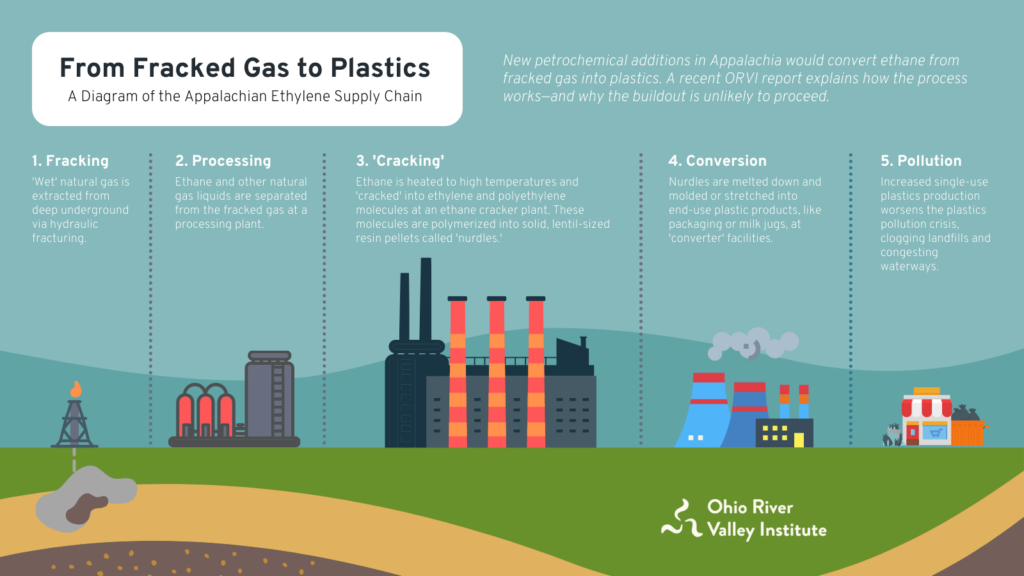

Fracking in Appalachia produces natural gas, along with a suite of other hydrocarbons, the most important of which is ethane. Petrochemical plants can “crack” ethane molecules f to produce ethylene and polyethylene, compounds that are then used to create lentil-sized plastic pellets known as nurdles. These nurdles are transported to other facilities, where they are melted down and injected into molds to produce end-use plastic products, like milk jugs, straws, and packaging.

The petrochemical supply chain has been seen as the lifeline for a fossil fuel industry careening toward collapse. But can ethylene and polyethylene development really save struggling natural gas companies in Appalachia?

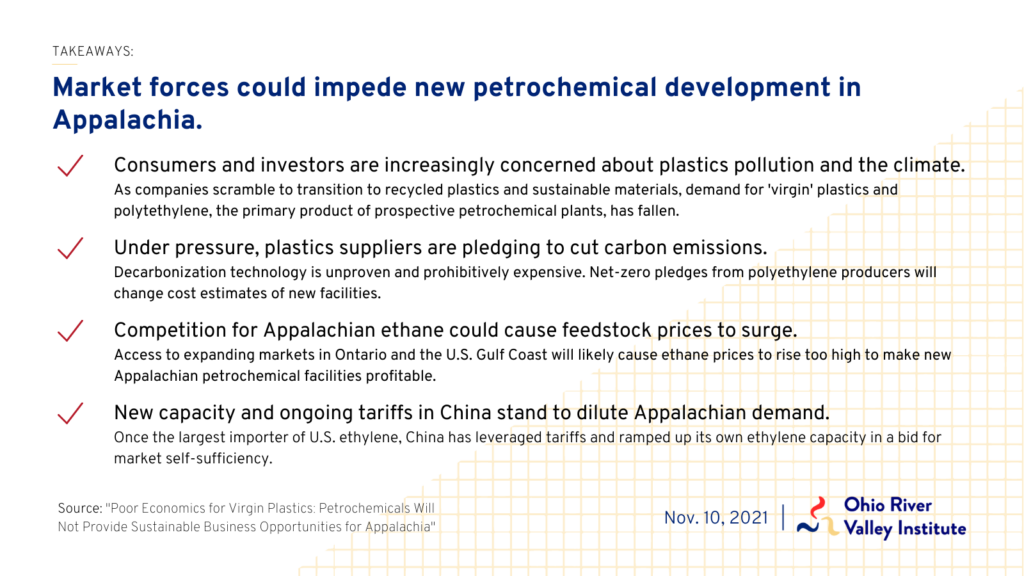

“Poor Economics for Virgin Plastics” outlines four major social and financial shifts that have restructured the plastics and ethylene markets in ways that are likely to hinder the profit margins of new ethylene- and polyethylene-producing facilities in Appalachia:

- Environmental concerns have slashed demand for virgin plastics. First, consumers and investors are growing increasingly concerned about the dire ramifications of climate change and the plastics pollution crisis. As the world’s oceans, streams, and waterways grow congested with discarded single-use plastics, societal pressures to reduce plastic waste air pollution have prompted plastics and packaging companies, fearful of losing their social license to operate, to pivot to products created from recycled plastic, plastic made from bio-based feedstocks, or other materials. Demand for non-recycled ‘virgin’ plastics and the ethylene and polyethylene from which they are made is shrinking, threatening the price margins of new petrochemical facilities.

- Under pressure, ethylene and polyethylene producers have pledged to reduce carbon emissions, shifting cost assumptions. Net-zero commitments pose a huge financial hurdle to new petrochemical development, as the technology required to cut back the carbon emissions of petrochemical facilities is largely unproven and prohibitively expensive. Innovations like carbon capture, use, and sequestration (CCUS) and advances in ‘green’ and ‘blue’ hydrogen will not be commercially viable for at least a decade. The incremental cost of incorporating these technologies would seriously hamper the profitability of new Appalachian petrochemical facilities.

- Competition for Appalachian ethane among existing petrochemical facilities in the Gulf Coast and Canada could cause a surge in feedstock prices. New forecasts for gas production and ethane supply in Appalachia suggest the region could support just one more ethylene plant, at most. And petrochemical expansions in Ontario and the U.S. Gulf Coast, together with new pipelines and increased export demand, have opened up new, profit-rich markets for Appalachian ethane producers, potentially driving up feedstock prices for facilities in Appalachia.

- New capacity and ongoing tariffs in China stand to dilute Appalachian demand. Shifting markets in China and across Asia have changed assumptions about demand for U.S. ethylene. China, one the largest importer of U.S. ethylene, began leveraging tariffs on American imports in the midst of a 2018 trade war. At the same time, Chinese companies have begun developing their own ethylene production capacity at a rapid pace, with a goal of leading the country toward self-sufficiency in petrochemical production. Accelerating development in other countries and lower-than-expected import demand in China and elsewhere in Asia could create a significant overhang of U.S. capacity.

With low ethylene and polyethylene prices projected to remain mired or worsen, chasing new petrochemical development in Appalachia is unlikely to yield returns. To some, the trend is clear. Investors, wary of sinking funds into soon-to-be stranded assets, have shied away from backing capacity additions in the region.

Leaders in the region would do well to acknowledge the writing on the wall, as well. The financial outlook for new petrochemical development in Appalachia is poor, and future capacity addition is improbable. Even if new development were to come online, these facilities are unlikely to produce the jobs and economic benefits promised by industry boosters. Instead, the time is ripe to pivot to alternative opportunities for economic development that can truly generate sustainable, shared prosperity in the long term.