Economic growth—the expansion and enrichment of business activity—is a narrow goal, easy to explain and understand: “More jobs for the community.” Economic development—expansion and enrichment of a community—is a broader goal: hard to explain, often fraught with disagreement over community needs. State and local governments invest heavily in strategies to create economic growth, but ‘development’ gets short shrift in the politically fraught and competitive process of industrial attraction. Siloed funding and separate stakeholders contribute to firewalls between strategies for economic growth and social needs.

The division is counterproductive in today’s economy. When common jobs paid enough to support a safe, modest yet decent standard of living, the private market responded to community needs, like supplying housing that workers could afford. Things have changed. Today, six of the ten largest occupational groups in Ohio leave a full-time worker with a small family eligible for SNAP, the federal food assistance program. Today’s private market no longer responds to the needs of workers.

Corporations locate factories and offices in places with lots of people from which they can draw a stable workforce. They scrutinize community assets that support the workforce: good schools, safe roads and bridges, clean water, and other basic factors. Five years ago the National Association of Counties reported that Amazon focused on diversity of housing options and availability of housing in its search for a second headquarters site. Yet today many places do not incorporate housing as an explicit component of economic strategy.

Housing development falls into a grey area between social and economic silos. Employers built worker housing after World War II to create a stable labor pool. The housing industry grew, serving the needs of an expanding middle class. Low-wage workers and workers of color were often excluded, so where the private market failed, the federal government stepped in and provided some subsidy to help some struggling families. Later, local governments stepped in and incentivized development of high-end, luxury homes to attract affluent people and corporate headquarters. Worker housing has fallen through the cracks. In a nation that needs 3.8 million more single-family houses and 7 million more rental units affordable to working class families, economic development strategies need to include supply of housing at all levels of the income spectrum.

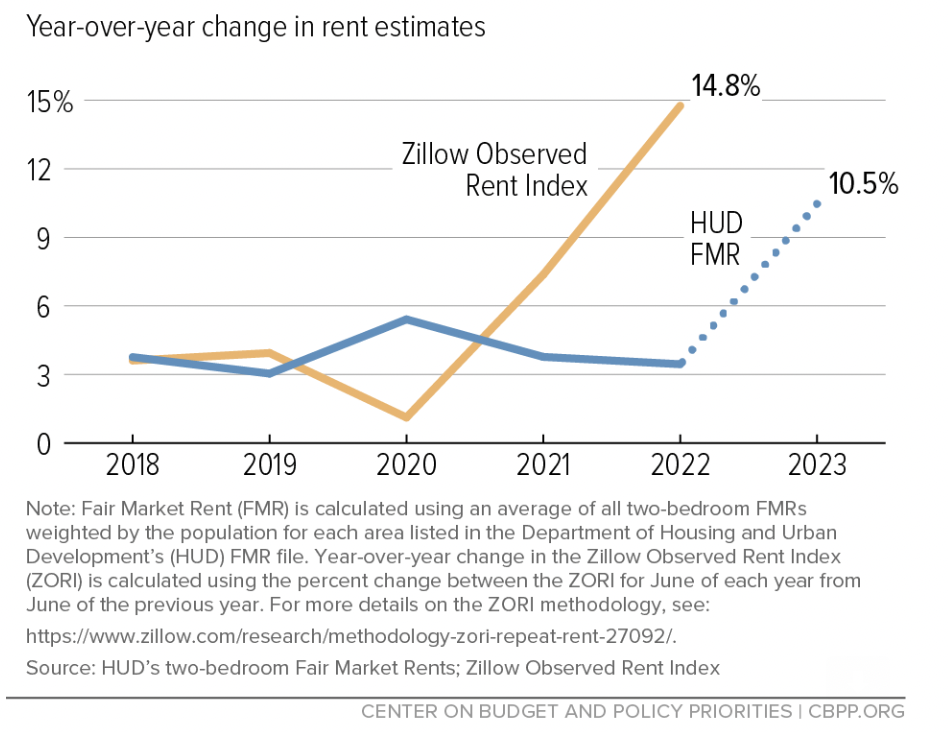

The rapid escalation in rental rates nationally leaves many working families struggling

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

In Ohio’s largely rural Hancock County, business expanded even during the pandemic and jobs were created but rental housing—the most common form of housing for workers—was scarce. The problem was complicated by lack of public transit from nearby communities that did have worker housing. “It’s a concern that Findlay has about a 98% occupancy rate for apartments,” said Tim Mayle, director of Findlay-Hancock County Economic Development, cited in the Findlay Courier. “The easiest way to address the workforce shortage, which other communities across the nation also face, is to have more people living in the community.”

The Virtuous Cycle

In 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma created an explicit economic development strategy that leveraged the city’s supply of affordable housing to attract remote workers. The city offered a $10,000 grant to eligible workers who committed to work remotely and live in Tulsa for at least one year. The program—boosted by pandemic ‘work from home’ orders—brought 1,200 new residents between 2018 and 2021.

Ohio’s cities and villages, dependent on the municipal income tax, have good reason to expand or leverage their existing supply of affordable housing. Ohio’s cities generally split the income tax between place of work and home. Cities with an employment base faced fiscal crisis during the pandemic as offices closed and commuters worked from home. Some never came back. Attracting new residents has a new urgency for Ohio municipalities from a revenue perspective.

Housing development contributes to a virtuous economic cycle. In the United States, home ownership is a primary rung on the ladder to the middle class. Construction and rehabilitation of homes stimulates a supply chain for lumber, concrete, windows, doors, and other building materials, many of which are supplied locally or regionally. Residential development employs many construction workers. It creates assets that anchor neighborhoods and expand the property tax base. The property tax primarily funds schools, so expanded housing contributes to good schools in the community. Good schools contribute to rising property values, creating wealth for residents and revenue for the community.

The downward spiral

Unmet community needs are a barrier to this virtuous cycle. In 2021, 20% of small families earning around $30,000 a year in the Southeast Ohio region lacked housing they could afford (with rent taking no more than 30% of monthly income); more than half of such families making less than $20,000 lacked housing they could afford. These families struggle to have enough food, clothing, medicine, and other necessities.

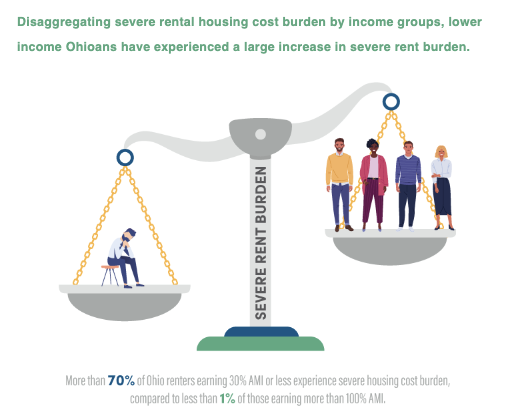

Workers of modest income struggle with the high cost of housing

Source: Ohio Housing Finance Agency

“My experience is that more families are doubled and tripled up in housing or living in garages, sheds or campers,” says Jack Frech, Executive-in-Residence at Ohio University and former director of Athens County Office of Jobs and Family Services. The hardship families face spills over into the communities.

“Local municipalities have a wide range of serious issues that are related to housing,” Frech points out. “Many have severe needs for adequate water and sewage systems. Utility costs are rising. Assuring public safety is becoming more challenging as labor shortages and increased costs have forced many communities to reduce their safety forces. Rising transportation costs have left poor families immobile.”

What Frech describes is the opposite of the virtuous economic cycle: it’s a downward spiral that stymies economic growth.

Political failure to meet basic needs

Public policy has not halted the downward spiral. The federal government provides public housing for some families of very low income, and housing subsidies to others, although only a small share of eligible families are helped through the inadequately funded programs. There are federal programs that subsidize development of worker housing, like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit and the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, which provide grants to states and localities for a wide range of housing activities. The national housing shortage highlights the inadequacy of these programs.

States also have programs to support affordable housing. The Ohio Housing Finance Agency promotes the Ohio Housing Tax Credit, the Multifamily Bond program, the Multifamily Lending program, and other programs to incentivize development. The Ohio Housing Trust Fund provides grant funding. Even when combined with federal incentives, the state’s tools have failed to redirect housing developers away from the higher returns they can get in the development of luxury housing.

“Each year, Ohio is allocated about $120 million of federal bond volume cap for multifamily development,” Ohio legislator Ron Hoops said in a recent press release on House Bill 650, which he is co-sponsoring with Representative Gail Pavligia. “Unfortunately, due to a lack of private sector investment in Ohio, much of this federal allocation has gone unused …”

Source: Ohio Housing Finance Agency

Turnaround is possible

“A poor community cannot boot-strap itself out of a housing crisis,” says Zach Reizes of Sunday Creek Horizons, an Athens County consulting group. “But local officials can take steps to turn things around.” A municipality or county can deepen the subsidy of federal and state tools with low-interest loans and grants. It can use bond financing and partner with land banks and housing agencies as well as developers. It can create programs that fund the rehabilitation of dilapidated houses and apartments, an important element in economic turnaround. After the closure of a major employer, the town of Centralia, in Washington State, focused on residential rehabilitation with energy efficiency improvements. This strategy raised property values, lowered costs, created jobs and recession-proofed the community, meeting social needs as an economic development strategy.

Wheeling, West Virginia, has anchored redevelopment strategies with worker housing. Urban Design Associates of Pittsburgh incorporates worker housing in its plans for Wheeling Heights. The Woda Cooper company, a Columbus-based firm, has created apartment buildings with affordable rents. Wheeling Councilwoman Rosemary Ketchum is an enthusiastic supporter. “I’m very excited for Wheeling to be able to embrace a diverse housing landscape. It’s one of the issues I think we’ve been dealing with for many years—a lack of quality affordable housing.”

It takes meaningful attention and investment.

The crisis in worker housing is well understood. The New York Times has analyzed the economic forces that reduced the supply of smaller “starter homes.” Economist Paul Krugman documents the rising cost of rent (up 25% nationally since the pandemic) and housing (up 40% since the beginning of the pandemic).

“Federal and state governments need to dramatically increase programs to develop affordable rental units and development of starter homes,” says Reizes. “It will take tremendous investment to rebuild the middle class. Housing is an essential part of that investment.”

The federal government is working on it. The Biden Administration plans to create new financing mechanisms to encourage affordable developments that the private market doesn’t fund, like manufactured housing and smaller, multifamily buildings. Officials will implement a new form of financing, “Construction to Permanent” loans (where one loan finances the construction but is also a long-term mortgage), by involving Fannie Mae in the purchase of these loans. New treasury guidance for use of State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) allocated through the American Recovery Plan Act expands eligibility for housing. Thirty states have committed almost $10 billion of these funds for affordable housing development and preservation.

This is an opportunity for communities up and down the Ohio River Valley. The state of Ohio recently provided $500 million in SLFRF funds to the state’s Appalachian counties. These funds could go a long way toward addressing development of worker housing and other pressing community needs.

The problem is bigger than housing alone.

Public programs to create and maintain worker housing stock should be an ongoing, integral part of the economic development toolkit. At present, the state’s 2020-23 development plan for Appalachian Ohio doesn’t have much to say about it. Recent “Opportunity Appalachia” grant awards mentioned housing only in passing. But the tide may be turning. Large employers like Intel and Amazon want diverse housing options. The Ohio Chamber of Commerce prioritizes policies to support and stabilize the workforce, including housing. Word will spread to local officials and community leaders promoting economic growth. A renewed focus on the needs of the workforce is overdue.

More is needed for balanced economic development.

“One-time funding may be good for defined infrastructure projects, but the ongoing housing issue will not be solved until we increase household income,” warns Frech. “Housing is critically important but in today’s rocky economy, so is raising the minimum wage, increasing Social Security, easing access to food aid, bolstering Veterans Administration benefits, and increasing other supports for working families.”