This post is the second in a four-part series based on a recent ORVI report on abandoned mine land (AML) issues. Figures cited below can be found in the accompanying report.

Abandoned coal mines have damaged thousands of acres of land, polluted hundreds of miles of streams, and are emitting tons of greenhouse gases. In a March post, I outlined the cost to clean up this historic damage from the coal industry: It is likely two or three times larger than the official $11 billion estimate. (Recently, that research was cited in a Congressional hearing on AML issues.)

AML damage tends to be located in economically ravaged places, and below I show that investing in cleanup could create thousands of jobs in former coal communities. But simply investing in cleanup isn’t enough—and I explore two policy areas that need to be strengthened to ensure these are good jobs and that they are accessible to those most in need.

First, if paired with stronger labor policies, AML cleanup could re-employ laid off coal industry workers who already possess skills needed for reclamation, could pay them a living wage, and could help build power in their workplaces. Second, creating a reclamation jobs program within a new Civilian Climate Corps (CCC) could ensure that cleanup jobs are accessible to those in poverty, who likely lack the job experience to be hired by private reclamation firms. Poverty in Appalachian AML counties—which contain 84% of remaining AML damage—is higher than in both their respective states and the nation, and those in poverty are disproportionately young, women, and people of color.

Imagine what a CCC might look like in 2022: hundreds of young people in West Virginia working side by side with union former coal workers to reforest the Alleghenies with native oak and shagbark hickory so that the rivers are once again filled with cold clean water. Biologists planning habitats for native crawdads and songbirds and reclamation teams operating the backhoes to make those plans real. They’d return home to their families in the evenings with enough pay to afford healthy food and childcare.

Take Harlan County, for example, where more than 4,000 acres of landslides, clogged streams, and other AML damage lingers. The Cumberland River begins in Harlan County below banks of thick rhododendron, not far from rare old-growth stands and Kentucky’s highest peak. In between the mine-scarred hillsides, 36 percent of people in Harlan County live in poverty. Since 2012, 1,700 coal workers have been met at their job sites with pink slips. They would be excellent candidates for a reinvigorated AML program, securing landslides that threaten to topple into their neighbors’ homes and treating the contaminants the spring rains bring down from old mines to the Cumberland’s headwaters and then downstream to three states and cities like Nashville. And, so might other residents of the county where 47% of Black people and 47% of children are in poverty, according to the 2019 American Community Survey. A jobs program could fundamentally change the impact of the AML program, opening up well-paying and dependable careers in the mountains, including for people of color and those without a formal education.

1. Drastically increasing funding for AML cleanup could create thousands of jobs.

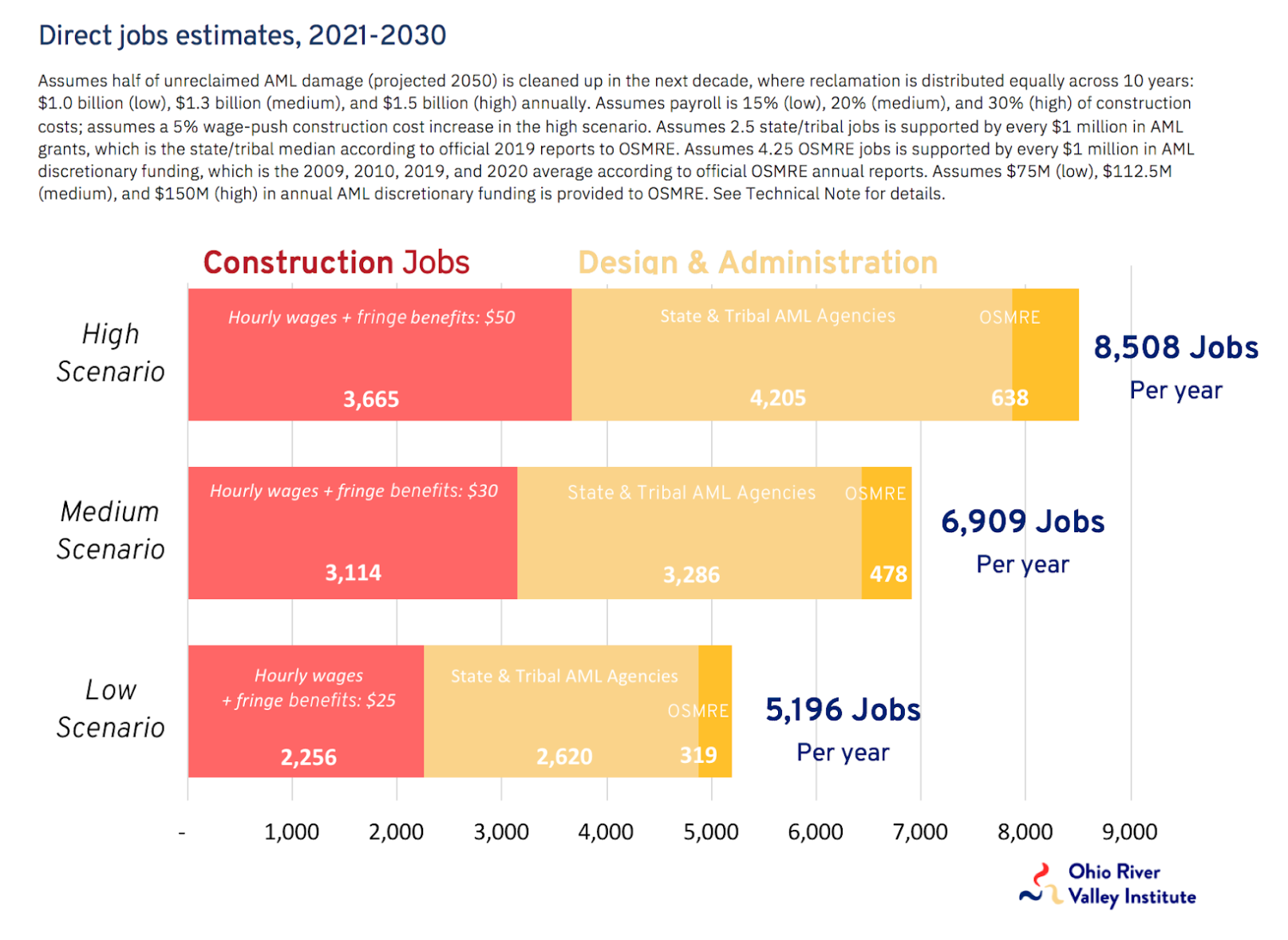

Outstanding AML damage will be $26 billion by 2050, according to my medium scenario estimate. (See this previous post for more on AML cost estimates). I recommend that Congress appropriate $13 billion for AML cleanup in the next 10 years, which would address half of the remaining $26 billion. This $1.3 billion in annual reclamation funding would be about five times higher than the $262 million in AML funding for FY2021 ($152 million in standard AML funding + $110 million in “AML Pilot” funds).

It’s a big uptick, but it’s money well spent. The economic devastation facing coal regions calls for reclamation to be front-loaded, and there are ongoing climate impacts from AML damage. Every day that damage lingers, there are costs to public safety, the economy, and the ecosystem. And damage worsens over time, becoming more costly to clean up the longer you wait. Front-loading cleanup would also create more job opportunities immediately. After the next decade, the remaining half of damage could be reclaimed between 2030-2050, perhaps by phasing down reclamation each decade, with 33% of remaining AML reclaimed in the 2030s and the last 17% in the 2040s. It’s entirely possible that costs will exceed our best estimates at present, and in this event, front-loading AML cleanup will put the program in a better position in 2030 than otherwise. In a future post, I’ll dig more into the finances of the AML program, including revenue projections and considerations for future funding.

The $1.3 billion in annual reclamation I’ve proposed would support 6,909 direct jobs per year from 2021-2030. The figure below is taken from page 26 of our recent report; see also page 27 for a discussion of the 10,384 induced and indirect jobs that would be supported. The number of jobs supported would slowly decline over time as funding phased down. But what do these jobs look like?

2. Without stronger labor provisions, AML cleanup jobs likely won’t be “good-paying union jobs” in many places.

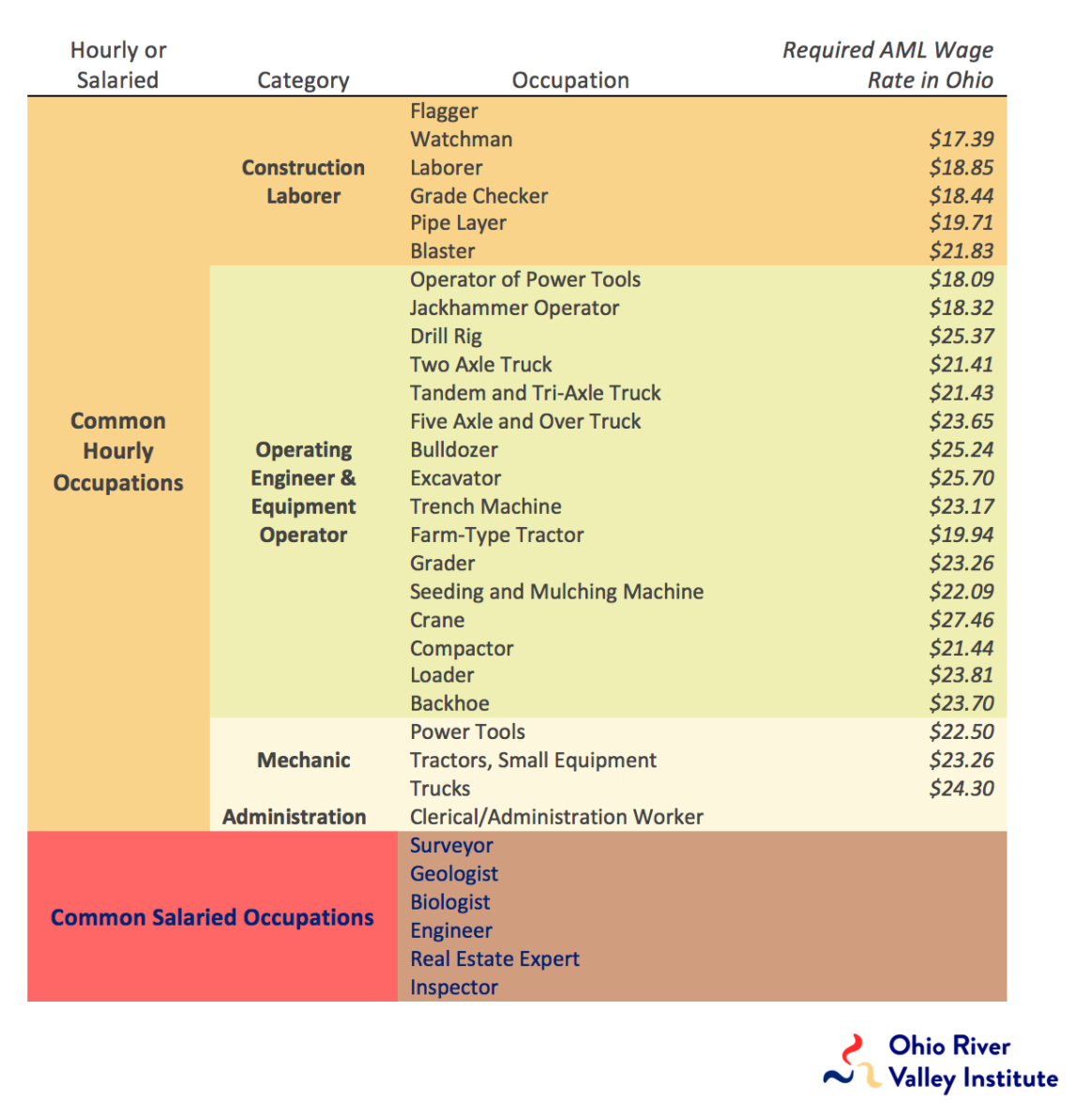

Many workers are necessary for AML cleanup, from government engineers, scientists, and managers who design and administer AML reclamation, to machinery operators, clerical staff, and tree planters who execute reclamation construction. Many AML construction jobs fall under two BLS Standard Occupational Categories: Construction Laborers (or, “Laborers”; SOC Code472061) and Operating Engineers (or, “Operators”; SOC Code472073). Specific occupations within these categories range from flaggers to operators of heavy machinery like excavators, many of which are listed below. But are they “good-paying, union jobs” that Biden and others have called for?

In general, AML construction jobs provide enough income to keep a family out of poverty but not enough to provide a living wage (i.e. a wage that allows residents to meet minimum standards of living)—though the lowest paid Laborers fall below the poverty line and the better paid Operators do earn a living wage. According to 2019 BLS data, the national median wage for Laborers is $17.72 and the national median for Operators is $23.55, across all industries (not AML-specific). But wage levels and cost of living vary considerably by state, and living wage levels depend on whether one or both adults in a family are working.

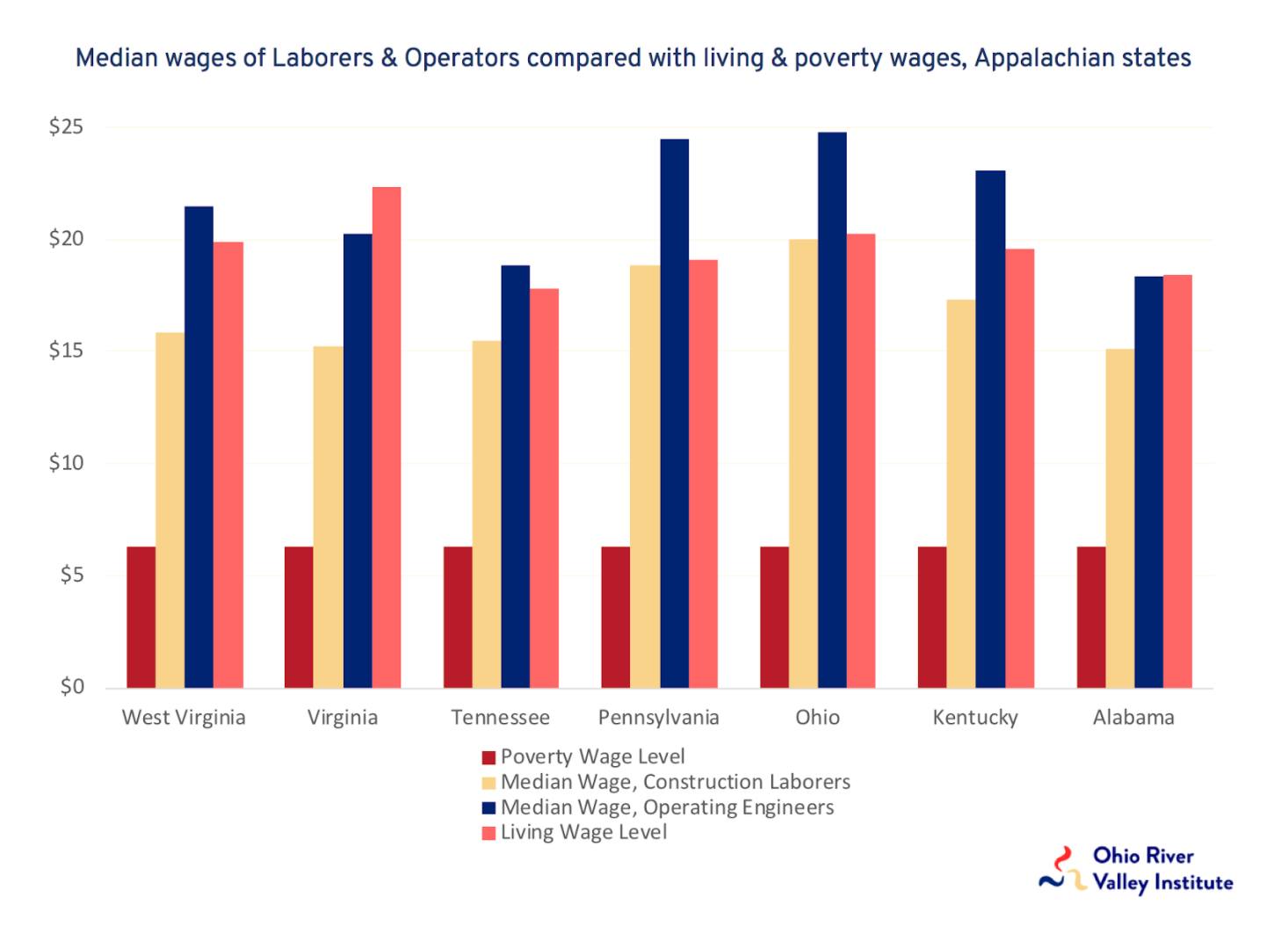

The figure below compares median wage levels of Laborers and Operators against the federal poverty level and state-adjusted living wage, for seven Appalachian states. The living wage estimates shown are for a family of four with both adults working, based on the MIT living wage calculator. It’s important to keep in mind that only the median wage levels are shown: there are many workers in each group making above and below this median. For example, lower-paid Operators don’t make a living wage, despite the fact that the median Operator wage is a living wage in 19 of the 25 AML states; and some Laborers on the lower end of their wage distribution in families with only one adult working don’t make above the poverty level. Though there is some variety by state, occupation group, and family situation, on the whole AML construction workers are making above poverty and below living wages.

Why aren’t these wages higher? At present, federal Davis-Bacon prevailing wage regulations do not apply to AML contracts, nor does the $15 minimum wage required for all federal contractors. A simple first step would be to apply existing prevailing wage regulations to AML contracts, and to apply Biden’s minimum wage for federal contractors to these projects as well—though, I argue the floor should be a living wage, not the $15 Biden has set to take effect in 2022. Though AML cleanup contracts flow through state and tribal agencies, they are federally funded and the AML program is federally administered by OSMRE, so prevailing wage and minimum wage laws for federal contracts should apply.

The extent of union density in the AML sector is unclear, but it is evident that unionization is very high in some states and very low in others. In Illinois where a state prevailing wage law has been in place for decades and where project labor agreements (PLAs) are utilized for AML projects, the vast majority of AML firms are union. In Illinois and in Pennsylvania—where there is also a prevailing wage law—AML workers are organized by unions like the Laborers’ International Union of North America (LiUNA) and International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE). In other states where these policies don’t exist and where overall union density is lower, it is likely that unionization is low or non-existent.

I have heard directly from unions that AML contracts are often too small for union contractors to realistically consider them. Policies like a) Project Labor Agreements (PLAs) for AML contracts, and b) aggregating smaller AML projects from similar geographic areas into a larger contract that is more realistic for union contractors are two measures that could increase union density in the AML sector. The AML sectors in Illinois and Pennsylvania show that these policies can help increase union density among AML firms without compromising the effectiveness of the AML program. It is no coincidence that Laborers and Operators earn higher wages in Pennsylvania than most other states—a state whose AML reclamation agency is one of the most well-respected in the country.

Other labor regulations for AML projects are needed too, and include: local and targeted hire provisions that would prioritize local workers and workers from certain communities (incl. women, racial or ethnic groups, the formerly incarcerated, and others), codifying what constitutes as an independent contractor so that misclassified workers don’t lose out on benefits and protections they are owed, standards that encourage unionization by requiring a share of project’s workforce come from a certified apprenticeship program, protecting the collective bargaining rights of reclamation workers, and more (see p34 of the report).

3. Without a public reclamation jobs program, reclamation work won’t be accessible to local people in poverty, who are disproportionately young people and people of color.

Many people in AML-damaged communities have never worked in the coal or construction sectors and thus lack skills and job experience that AML contractors are seeking. Poverty in Appalachian AML counties –which contain 84% of remaining AML damage— is higher than in their respective states and 1.5 percentage points higher than the nation. And within AML counties, much like elsewhere in the U.S., poverty is higher among people of color, women, young people, and those with less formal schooling.

It’s likely that many of those in poverty lack the construction experience that would make AML jobs accessible to them. So, if we want AML jobs to benefit the poorest in AML communities, we have to do more to ensure they can access these jobs. A public reclamation jobs program within a Civilian Climate Corps (CCC) could fill this key gap by providing on-the-job training and targeting groups left out by the private market. And it would raise the bar for wages, safety, and reclamation techniques in rural construction markets.

Public jobs programs in coal mine reclamation are not without precedent. The Pennsylvania AML agency currently employs two crews of 12 full-time permanent staff each that together complete an average of 150 small reclamation projects annually. (See p38 of the report for more on these case studies). From 2012-2019, the in-house crews completed 78% of the state’s total number of projects in that time period, though these projects were only 4% of the total reclaimed acreage. Officials in Pennsylvania note that the in-house crews enable the agency to address emergencies more quickly than bidding them out, and that the crews typically don’t complete larger projects not because of a lack of skill but because the state AML agency doesn’t have the budget to invest in the large heavy machinery needed for some projects.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Ohio Division of Civilian Conservation (DCC)—a workforce training program that provided temporary jobs for young adults—had crews that completed 40-50 small mine reclamation projects annually for the Ohio AML agency. While not the largest projects or projects that required significant engineering compliance, many of the projects did require operation of heavy machinery, including bulldozers and backhoes. An official with the Ohio AML agency at the time explains that the quality of work of the projects was high, though sometimes took longer than usual.

A public reclamation jobs program could have employment tracks for both temporary and permanent jobs, and the program could be structured so that some share of annual reclamation funding is contracted from OSMRE to a new CCC that houses the reclamation crews. Nesting the reclamation crews within the CCC is also advantageous in that reclamation work is seasonal and reclamation crews within the CCC could easily shift to other conservation-type work in off-season months. For example, in the colder months when reclamation construction slows down, crews could shift to maintenance projects at state parks and other public lands or to seasonal wildland firefighting.