On June 15, 2020 a group of seven prominent economists and policy analysts from leading universities in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia and a former Pennsylvania Secretary of Environmental Protection, wrote a public letter to the governors of the three states warning them that economic development strategies based on a massive buildout of the region’s petrochemical industry are infeasible and recommending that the governors and other policymakers explore more viable and sustainable strategies.The following is a background brief examining the factors that caused those who signed the letter to come to their shared conclusions.

The letter’s signers included Ted Boettner, Executive Director of the West Virginia Center on Budget & Policy; Wilfrid Csaplar, Jr. PhD, Professor of Economics at Bethany College; John Hanger, Energy Analyst and Former Pennsylvania Secretary of Environmental Protection; Nicholas Muller, PhD, Associate Professor of Economics, Engineering, and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University; Mark Partridge, PhD, Professor, Swank Chair in Rural-Urban Policy at the Ohio State University; John B. Russo, EdD, Founder and former Director of the Center for Working-Class Studies at Youngstown State University; James Van Nostrand, Associate Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Energy and Sustainable Development at the West Virginia University College of Law; and Amanda Weinstein, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Akron.

BACKGROUND BRIEF FOR

A LETTER TO THE GOVERNORS OF OHIO, PENNSYLVANIA, AND WEST VIRGINIA

June 15, 2020

The ongoing coronavirus crisis has shone a spotlight on the importance of political leadership and policymaking to protect our lives and health and also to help communities and families become economically resilient and prosperous. But, in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia our aspirations to health and prosperity are threatened by the very policy we thought would help achieve them.

Under multiple governors, both Republican and Democratic, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia have embraced a vision of economic prosperity based on a buildout of the region’s petrochemical industry that includes an array of processing plants and a fleet of ethane crackers supported by immense natural gas liquids (NGL) storage facilities. We are told these facilities would give rise to multitudes of new manufacturing businesses in plastics and in chemicals that would provide more than 100,000 good-paying jobs (1).

Supporters of this economic development strategy acknowledge that, if it happens, it will come at a cost to the environment, which will see a significant spike in the emission of greenhouse gases and local air and water pollution. However, they argue that the added jobs and prosperity resulting from the buildout will more than outweigh those costs. Consequently, public debate over the envisioned petrochemical/plastics buildout has generally been cast as a case of “jobs versus environment”.

However, a group of economists, engineers, and policy analysts who are affiliated with some of the region’s leading institutions (2) concludes that, in addition to environmental and health concerns, there are also compelling economic and technological reasons to believe that such a buildout is unlikely to happen and, if it does, it is unlikely to result in the expected blossoming of jobs or the level of prosperity that we have been led to expect. For that reason, they believe the states of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia should stop squandering resources and effort in pursuit of a vision of a flawed vision and concentrate instead on alternative economic development strategies that are more feasible and sustainable.

Why the petrochemical boom is an economic non-starter

A recent report (3) from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) found that an ethane cracker proposed by PTT Global Chemical (PTTGC) and its partner Daelim for Belmont County, OH has become too risky an investment to go forward. The reasons cited include:

- Reduced prices for ethylene and polyethylene will hinder price growth going forward

- Ethylene production overcapacity will persist at least through the year 2026

- Competition in the resins market will increase as major oil companies seek new markets for crude oil

- Investment will threaten sponsors’ credit ratings

- The project’s chief sponsor, The Thai government controlled PTTGC, is vulnerable to changes in US government trade and energy policy

While the signers of the letter to the governors agree with the IEEFA report’s conclusions (and, indeed, since the report was issued, PTTGC has announced an indefinite delay in a final investment decision for the Ohio cracker), they see additional economic and technological issues not contained in the IEEFA analysis that make the challenges facing the Ohio cracker project:

- Applicable to any cracker project that might be contemplated for the Marcellus/Utica region

- Of an enduring character that will cause them to outlast the current economic crisis.

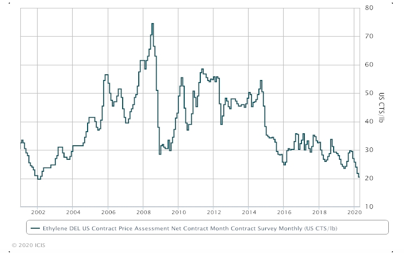

Therefore, prospective enterprises that depend on the construction of 4-5 crackers in the region, including storage facilities such as the proposed Appalachian Storage Hub (ASH), and downstream businesses in plastics manufacturing and other fields, are unlikely to materialize. And, without expansion of those enterprises, the promise of major job growth in the region evaporates.The economic challenges begin with cracker profit margins, which had declined by half between the beginning of 2018 and the end of 2019 and are unlikely to return to levels sufficient to warrant investment in new projects.

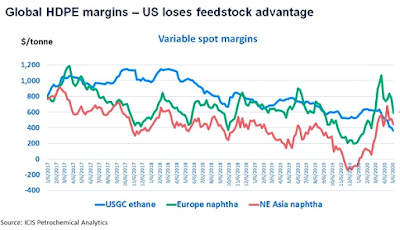

Meanwhile, the feedstock cost advantage ethane has enjoyed since the fracking boom over its oil-based competitor, naphtha, had by the end of last year already narrowed substantially from its levels in 2013 and 2014 when 4-5 regional Appalachian crackers were first being talk about. Now, in the wake of recent events, the cost advantage has disappeared altogether. For the advantage to be restored to a level sufficient to generate margins acceptable to investors, the price of oil would have to recover from its current level of around $30/barrel to well over $50 and perhaps more than $60.

As recently as two years ago, prices in the $60s were not adequate to save the proposed ASCENT cracker in Wood County, West Virginia, which was delayed for four years before being cancelled in 2019. At present neither the EIA nor any major analytics firm forecast a return to prices at that level. That’s in part because major oil companies see global demand for fuels flattening. Consequently, they are reallocating resources to the still-growing petrochemical market. In 2018, the IEA projected that, in the decade of the 2020s, petrochemicals, which currently command 14% of oil consumption, will generate 30% of total demand growth. Much of that growth, if it takes place, will come at the expense of competitive feedstocks such as the ethane produced in Appalachia.

Finally, prices for ethylene and polyethylene have been consistently falling since early 2018, long pre-dating the coronavirus crisis and the most recent plunge in oil prices.

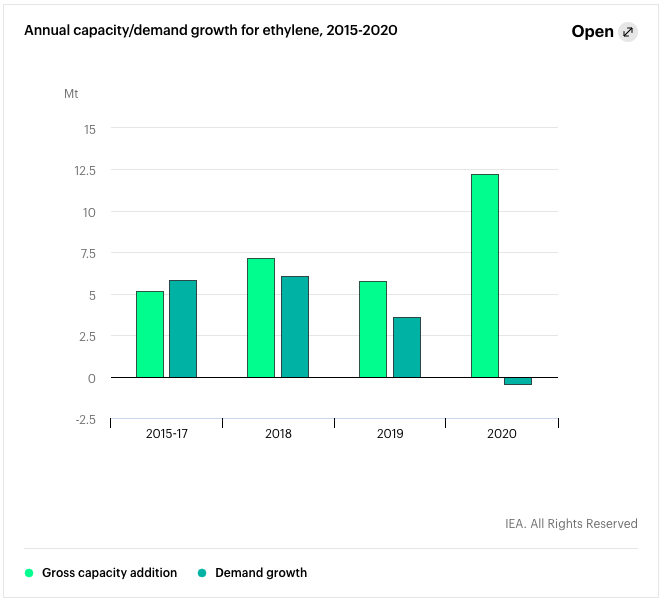

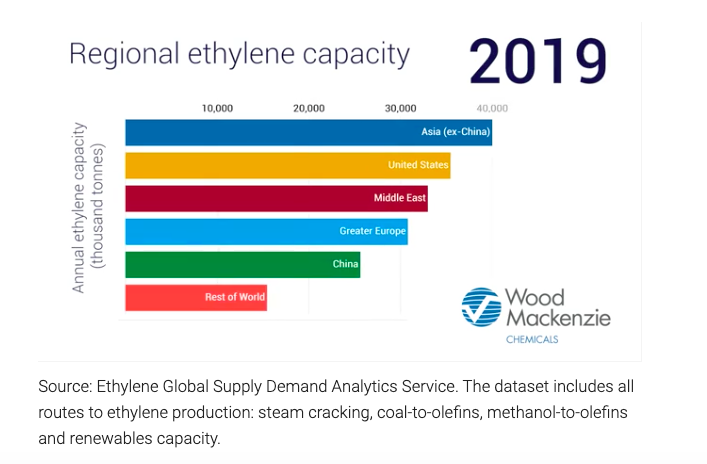

At the same time prices and margins are falling, competition is exploding. As noted in the IEEFA report, cracker capacity in the US, principally along the Gulf Coast, has increased by 50% in the last two years, creating a condition of overcapacity that the IEEFA analysis doesn’t see closing until 2026.

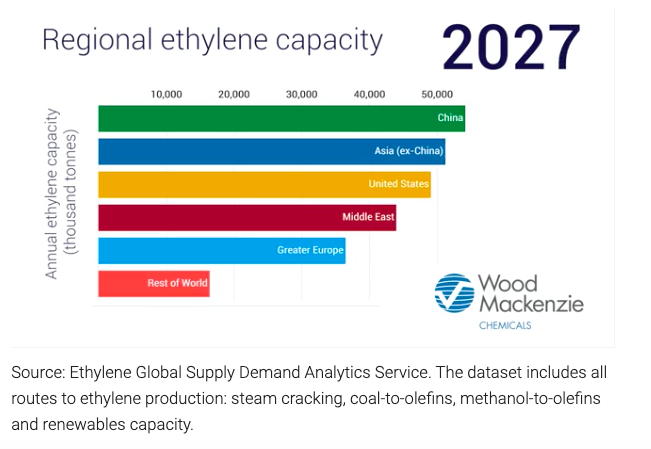

However, not noted in the IEEFA report is what Wood-MacKenzie characterizes as a “meteoric expansion” of ethylene capacity in China over the next five years, surpassing even the US expansion. As a result, IHS Markit forecasts a plunge in global cracker utilization rates in coming years.

Another factor mitigating against Appalachian petrochemical expansion is the financial condition of the region’s gas drilling industry which was dire before the recent crisis. More problematic for petrochemical expansion prospects is the fact that the best cure for the industry’s financial ills – a rise in natural gas prices – would also reduce the competitiveness of Marcellus/Utica ethane in petrochemical markets. We can add to that questions about the speed of general economic recovery and whether demand growth for plastics and chemicals will meet pre-crisis expectations.

Finally, in addition to the many market pressures facing petrochemical expansion, government climate and pollution policies may also hinder growth of the plastics market. Petrochemical and plastics production is highly emissions intensive, which makes it vulnerable to an assortment of greenhouse gas reduction measures, such as carbon pricing and cap and trace policies, for which pressure is growing. Meanwhile, both national and regional governments, including recently China, are enacting single-use plastic bans, bag bans, and other measures designed to reduce plastics consumption and pollution.

As the IEEFA report points out, the multiplicity and variety of risks associated with any Appalachian cracker projects will likely be intolerable to investors, who not only need to see these trends reversed, but must be convinced that they will stay reversed. But, even if investors could be reassured, there are technological reasons why construction of a fleet of crackers will not produce the immense job growth that proponents claim.

Why “the shale crescent” cannot become “the new Gulf Coast”

When proponents of a Marcellus-region petrochemical buildout tout the potential for creating tens or even hundreds of thousands of new jobs, they’re not for the most part talking about the crackers and storage facilities. While the cracker in Beaver County, Pennsylvania employs thousands during construction, the number of permanent jobs it will provide is about 600. The figure for the Belmont County, Ohio cracker would be about 400. And the figures for storage facilities, including the Appalachian Storage Hub, would be only a fraction of that – hardly economic game-changers even when multipliers are considered.

The bulk of expected job growth is associated with expansion of the downstream manufacturing sector that proponents tell us could rival that of the Gulf Coast.

But, the Gulf Coast’s manufacturing industry is built on bountiful supplies, not just of ethylene and polyethylene, but also on propylene and aromatics, including benzene, toluene, and xylene, which are necessary for the manufacture of as much as half of all plastics products, including most heavy duty plastics. Cracking ethane yields only small amounts of propylene. And ethane is not easily converted into aromatics. For that reason, the region’s natural gas probably cannot cost-effectively provide ingredients that are necessary for a large portion of the activities that make up the Gulf Coast’s manufacturing sector.

Second, the IEA projects that more than half of global growth in demand for plastics will take place in Asia and developing countries. Less than 10% will take place in North America. Consequently, most of the ethylene and polyethylene produced by Marcellus/Utica region crackers, if they are built, is likely to be shipped to manufacturers outside of the region and the country.

In summary, because the region’s natural gas can’t provide necessary raw materials for a large segment of the plastics market and because the fastest growing markets for the product that would emanate from Appalachian crackers are on other continents, their construction is unlikely to give rise to a robust manufacturing sector. And, if manufacturing doesn’t grow, then the promise of jobs and economic prosperity largely evaporates.

We can’t dismiss the health and environmental risks

This brief concentrates primarily on the economic and technological flaws in the vision of petrochemical prosperity because they are less well-known and little talked about. However, that focus does not in any way diminish concerns about the effects a petrochemical buildout would have on climate and on the health of residents in Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and beyond.

Indeed, the ongoing coronavirus crisis has enabled us to see more clearly than before the relationship between increased levels of particulate pollution and higher rates of death from cardiovascular and upper respiratory conditions. A newly-released study from the T. H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University finds “that someone who lives for decades in a county with high levels of fine particulate pollution is 15% more likely to die from COVID-19 than someone who lives in a region that has just one unit (one microgram per cubic meter) less of such pollution”. The study goes on to point out that the new findings align with known connections between fine particulate matter exposure and higher risk of death from many other cardiovascular and respiratory ailments.

Ethylene cracker plants, processing facilities, and downstream manufacturers are major emitters of fine particulate matter as well as volatile organic compounds that have been linked to various cancers. And the crackers would be built in the midst of a population that is among the nation’s most vulnerable. The prevalence in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Valley of cancers, cardiovascular disease, upper respiratory disease, obesity, diabetes, and other conditions that place people at risk is already among the most elevated in the nation.

Finally, every cracker plant that would be built would emit millions of tons of carbon dioxide equivalents each year at a time when the region and the world desperately need to decarbonize in order to avoid frightening levels of disease, destruction, and upheaval on a global scale.

We need better, cleaner economic development strategies and they’re out there

Our region has the opportunity to vigorously pursue clean energy industries – electric vehicles, energy storage, wind power, solar power, and especially energy efficiency — which already employ more than 175,000 workers (4) in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia – three quarters of them in manufacturing and construction.

Building and retrofitting homes and commercial spaces to make them more energy efficient creates jobs up and down the skills ladder and drives revenue to local contractors, manufacturers, and building maintenance and remodeling companies. Meanwhile, homeowners, building owners, and tenants enjoy lower utility bills and healthier, more comfortable spaces. And greenhouse gas emissions plunge.

Communities in the Marcellus/Utica region possess great economic assets, including an experienced and able work force in the trades and professions; culturally rich, diverse, and affordable communities; and an ecosystem of suppliers and service providers capable of supporting enterprises in manufacturing, high tech, finance, and the arts.

We must accept and deal with the fact that declarations of an emerging “shale crescent” and visions of economic prosperity driven by an expansion of the petrochemical industry are illusions. We should stop squandering public funds and other resources in pursuit of industries that, even if they were to grow, would not produce the jobs and prosperity we seek, but would inflict serious damage to our health and environment. And we should turn our efforts to alternative economic development strategies, which can build on our established businesses and communities and which would support every community in our region.

[1] The American Chemistry Council, “The Potential Economic Benefits of an Appalachian Petrochemical Industry”, May 2017 https://www.americanchemistry.com/Appalachian-Petrochem-Study/

[2] The University of Akron, Bethany College, Carnegie Mellon University, The Ohio State University, West Virginia University, and Youngstown State University

[3] The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, “Proposed PTTGC Petrochemical

Complex in Ohio Faces Significant Risks”, March 2020 https://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Proposed-PTTGC-Complex-in-OH-Faces-Risks_March-2020.pdf

[4] USEER Energy Employment by State 2020