Here’s a name you don’t often read in Appalachian history books: Bill Worthington.

Bill was a Black coal miner from Harlan County, Kentucky, and a member of the United Mine Workers of America. Bill played a pivotal role in historic labor disputes in Harlan County in the 1970s and helped organize the National Black Lung Association. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Lung Association fought for the recognition of black lung as a workplace disease and for state and federal policies related to black lung, and continues to this day to advocate for medical assistance and other policies to support miners with the disease.

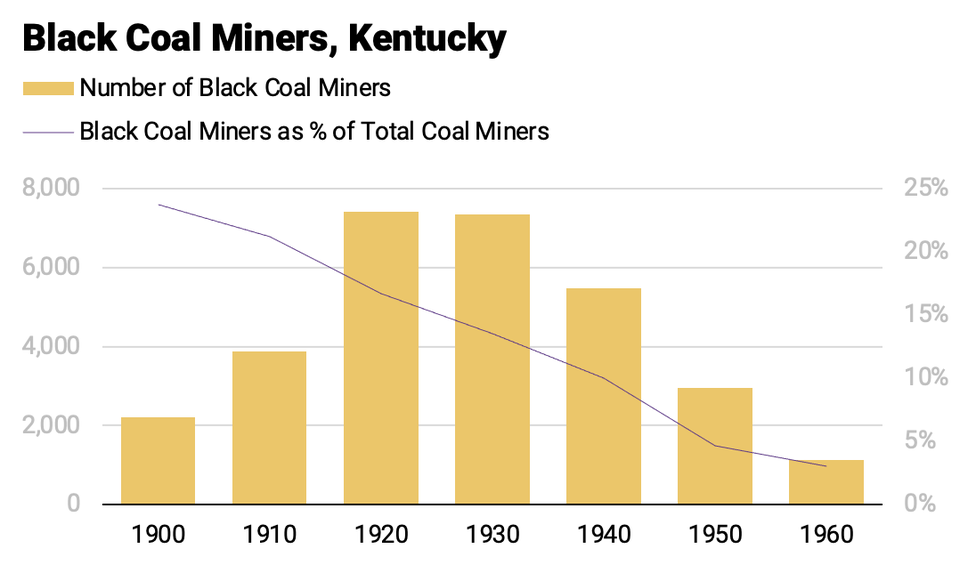

Though many Americans don’t know it, Black Appalachians were critical to the booming of the coal and steel industries and their historic contribution to the national economy. Black workers made up a significant share of the workforce in the steel mills of the region. In Western Pennsylvania, Black workers made up 13% of the region’s steelworkers in 1918. Similarly, 1 in 11 coal miners in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and West Virginia in 1930 were Black. Nearly a quarter of West Virginia coal miners were Black. Black employment in the coal sector has declined steadily since the 1930s, but Black workers remain important members of the coal mining workforce: Some are among the white, Black, and brown union miners currently on strike at the Warrior Met Coal mine in Alabama, the longest ongoing strike in the nation.

This month ORVI kicks off a virtual listening session with the Black Appalachian Coalition about the petrochemical industry’s impact on Black communities in the region, so we’re highlighting research from a joint report we released with the Black Appalachian Coalition this time last year. (You can learn more about the session below or register here).

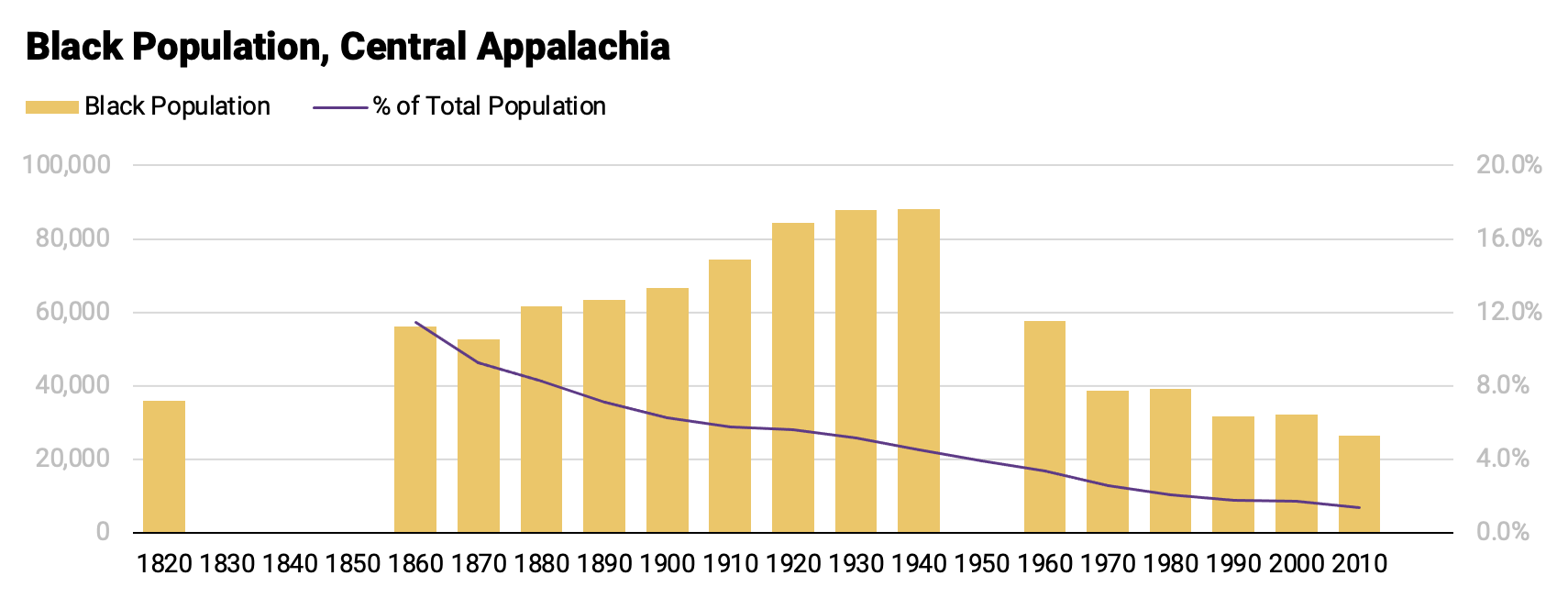

Even the areas of Appalachia with the smallest Black populations today were shaped by centuries of Black contributions. In the Central Appalachian counties of Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia—the predominantly rural subregion of Appalachia often considered to have little or no racial diversity—nearly one in six people were Black in 1820. For context, that is a higher percentage than the current national Black population. The relative share of Black Appalachians has since steadily and significantly decreased, shown in the figure below based on census data. Today tens of thousands of Black people still call Appalachia home, including in its many rural counties.

Economic security is hard to come by in Appalachia, and that’s doubly so for Black households. The share of Appalachians who cannot afford basic necessities is much higher than the share of Americans overall. In 2019, the Appalachian regions of Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia had a combined rate of 15.5% of people whose incomes fell below the federal poverty line. That number almost doubles for African Americans: 30.5% of Black Appalachians had incomes below the federal poverty line. That’s approximately 130,577 Black people that had incomes below the poverty line. The racial gaps were the largest in Pennsylvania and Ohio: the Black poverty rate was about 19 percentage points higher than the white poverty rate.

Related research on the unemployment rate by the Council for Economic and Policy Research shows that the national unemployment rate for Black workers has been about twice as high as the white unemployment rate for 60 years.

One policy that could help is a subsidized employment program. Here’s how it works: the government provides subsidies to businesses to cover some or all of the wage costs of hiring new workers. The program could target job creation in areas with persistent distress, such as much of Appalachia. The policy “would improve employment prospects for everyone living in such communities, but it would disproportionately benefit Black people because Black communities tend to have high rates of joblessness,” write Algernon Austin and Annabel Utz at the Center for Economic and Policy Research.