Plastics are a problem. The world is awash in plastic. It is a major contributor of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and poses risks to workers and communities, especially environmental justice communities. Micro- and nanoplastics are everywhere, and we are learning more and more each day about the risks associated with the thousands of chemicals involved in the plastic lifecycle.

Plastic recycling would seem to provide a solution. But plastic recycling has struggled for 30 years, with recycling levels never reaching more than 10% of the plastic produced annually. Current estimates are even lower, with US recycling rates only 5-6% of plastics generated in the US, according to the World Economic Forum.

“Chemical recycling” is the latest proposed solution to the growing plastic production and waste problem. Unlike mechanical recycling, which reprocesses plastic polymers largely by physical processes, chemical recycling is a broad category of technologies that use chemicals and/or heat to break down plastics to the polymer, monomer, or chemical feedstock level. It comprises three main technologies: purification, depolymerization, and conversion (primarily pyrolysis and gasification). These technologies purport to provide a solution to the limitations of current mechanical recycling by providing a pathway to near-virgin quality plastic.

But, as this report will illustrate, chemical recycling is a false solution, one that ignores the health impacts inherent in the various chemical recycling processes. It also sidesteps the technical and economic headwinds that have, to date, stymied the industry. The pursuit of chemical recycling diverts attention and resources from solutions that would address the growing problems associated with production, use, and end-of-life treatment of plastics.

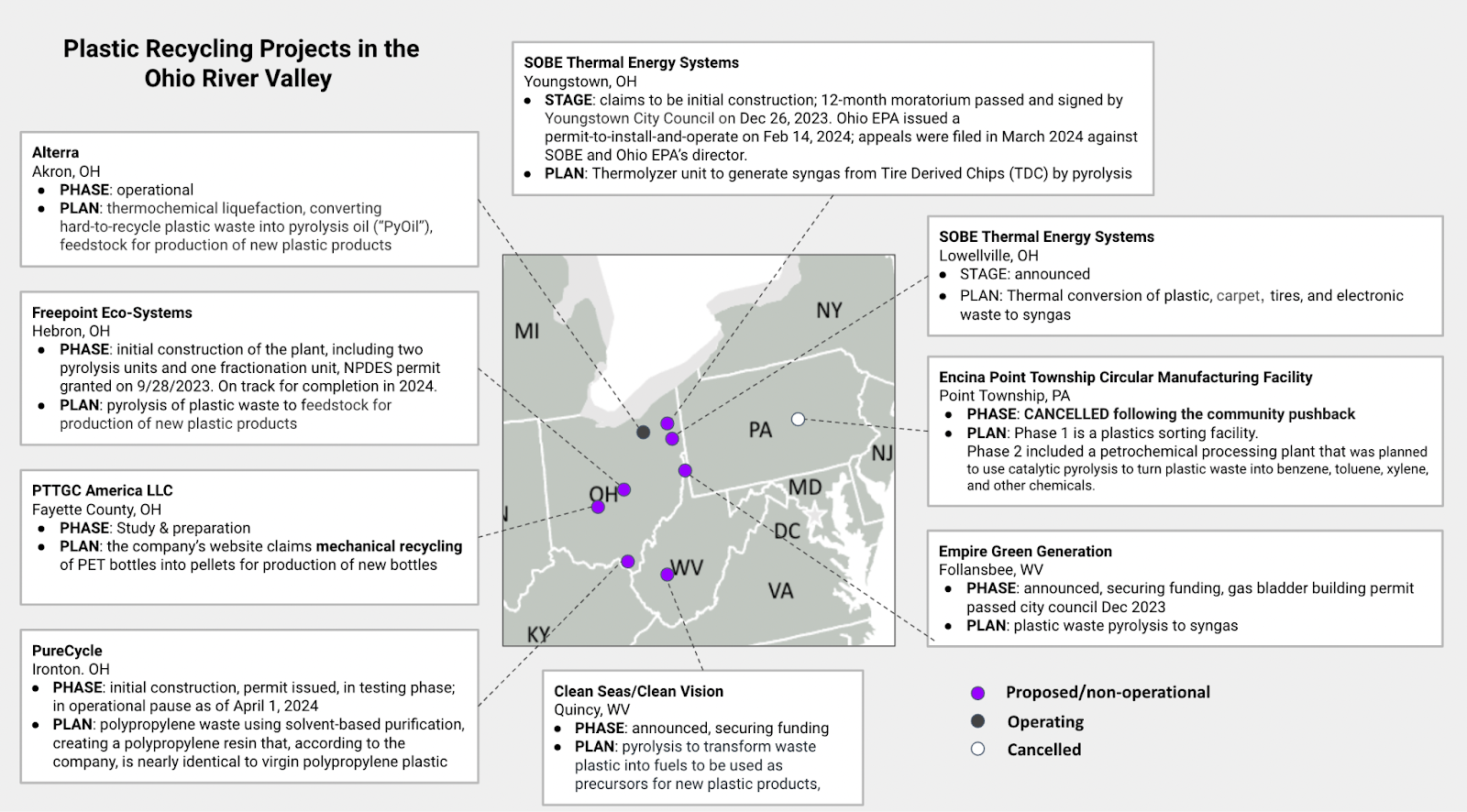

After decades of research and significant private and public investment, only ten chemical recycling facilities operate in the US, and none produce at scale. The technology used in various types of chemical recycling in each of these facilities remains in the pilot or demonstration stages. Two of the ten operating chemical recycling facilities are in the Ohio River Valley: Alterra and PureCycle. Both are in Ohio. Dozens more are planned throughout the country, including several in the Ohio River Valley. Many proposed projects have been canceled or delayed, likely due to the poor economics of the industry coupled with local opposition as citizens broadcast the dangers posed by chemical recycling.

Sources: Jess Conard, M.A., CCC-SLP (Beyond Plastics), Ohio EPA, Oil and Gas Watch, and public corporate records.

All chemical recycling processes are toxic. When waste plastics are processed through chemical recycling, the additives and other contaminants present in these plastics can be transferred to emissions, wastewater, solid waste, or output products. Many of the processes also involve flammable compounds or solvents that can pose fire risks. These processes can contaminate residual hazardous waste streams with Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) and cause contamination of the chemical recycling output. If the output is used as fuel, then the POPs may be emitted into the atmosphere as the fuel is burned. To produce recycled plastic material, outputs of chemical recycling processes must be further integrated into an already toxic plastic production process that generates toxic Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), such as benzene, toluene, and other chemicals of concern.

Risks from chemical recycling particularly impact workers and the surrounding communities. Chemical recycling facilities tend to be built near petrochemical supply chains. Since existing petrochemical facilities are often located near communities of color and/or low-income communities, the source of emissions is concentrated, as is the environmental injustice burden.5

Despite the hype around chemical recycling, most chemical recycling facilities do not, in fact, recycle plastic. Many produce only fuel, which does not meet many definitions of recycling which explicitly excludes technologies that do not reprocess plastics back into materials, but into fuels or energy.

These facilities use confounding terms like “advanced” and “recycling,” when in reality they are just producing fuels from plastic, and are, therefore, not circular or recycling at all.

According to Veena Singla, a senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), “The benefit of recycling comes when you return materials into the production cycle, which reduces the demand for virgin resources. Now if you’re taking plastic and burning it as fuel, it’s not feeding back into plastic production. And so to keep making [new] plastic, you have to keep extracting fossil fuel.”

Furthermore, depending on the type of plastic that enters a pyrolysis vessel, the output (or end product) may shift from what was originally planned and announced publicly. These changes make it challenging for local communities to fully analyze the impact of a proposed chemical recycling facility.

The potential benefits of chemical recycling have been touted, in particular, by the petrochemical industry, which is part of the fossil fuel industry. The petrochemical industry implies that difficult-to-recycle plastic can be recycled safely, all while creating economic benefits for local communities. Why is the fossil fuel industry so bullish on chemical recycling? Because petrochemical and oil and gas companies see plastic production as Plan B, which will fuel their growth even as the energy transition evolves and demand for transport fuel declines. Annual virgin plastic production has grown rapidly over the past decade and its rapid growth is forecast to continue. Petrochemicals, which include plastic, currently account for roughly 12% of oil use, but the sector is expected to surpass oil demand from trucks, aviation, and shipping by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). In short, petrochemicals are vital to the oil and gas industry’s future.

Recent documentation has revealed that the petrochemical and fossil fuel industries have, for decades, promoted plastic recycling with full knowledge that it is a false solution to the plastic problem. These industries have deceitfully suggested recycling would address the plastic waste problem, allowing them to continue to produce ever more virgin (or new) plastic.

Beyond implying that chemical recycling is a magic solution for plastic waste, the petrochemical industry lobbies for reduced federal and state-level regulation of the two most common types of chemical recycling, pyrolysis and gasification. The industry claims that these technologies should be considered manufacturing, rather than solid waste incineration, which requires stricter pollution controls and oversight. Such deregulation would further risk workers and local communities.

Economic benefits of plastic recycling, particularly chemical recycling, have not borne fruit, and are unlikely to. The economics of chemical recycling appear insurmountable without billions of dollars of investment. Thus far, the private sector has been slow to move forward with the scale of investment needed. No wonder, as the economic viability of the industry depends on several factors, many of which lie outside the industry. Beyond capital expenditures (CapEx), creating positive operating cash flow depends on low waste feedstock costs, collection and sortation of plastic waste, and high and stable prices for recycled plastic.

Recycled plastic must compete with abundant, low-cost virgin plastic. The US is now the world’s largest producer of both natural gas and oil, both of which are feedstocks for plastic production. This glut of natural gas and oil has fueled a production boom for petrochemicals and plastics, primarily along the US Gulf Coast. At the same time, China has ramped up its petrochemical industry. The result is an oversupply of virgin plastic production. Experts believe the glut could last for a decade.

While low-cost virgin plastic is a challenge facing mechanical recycling, it is more challenging for chemical recycling. The technology for chemical recycling processes is unproven, yields are lower, its infrastructure is immature, and the market for its product, while promising, is still undeveloped.

Chemical recycling is toxic and dangerous, particularly for those who work in or live near a recycling facility. Other economic development projects in the region would reap greater rewards than pursuing unproven, unsafe technologies with no realistic hope of job creation or other markers of financial viability. The Ohio River Valley Institute’s Roadmap for Industrial Decarbonization in Pennsylvania, for example, provides many alternative paths that focus on industrial development to create shared prosperity while addressing urgent decarbonization goals.

Chemical recycling is not the solution — either for plastic pollution or for local communities.

Key Findings:

- Chemical recycling is an energy-intensive process that produces very little virgin-like plastic. Unlike mechanical recycling, which reprocesses plastic polymers largely by physical processes, chemical recycling describes highly engineered technologies that use chemicals, pressure, and/or heat to break down plastics to the polymer, monomer, or chemical feedstock level. These feedstocks can be potentially further reprocessed into virgin-like quality plastic. But chemical recycling (also called advanced, or molecular recycling), converts only 15-20% of plastic waste into recycled plastic products. Most end up as emissions, process fuel, or hazardous waste.

- The most common forms of chemical recycling are not recycling. Many so-called recycling facilities simply convert plastic waste into fuel, which is not circular. It does not meet the definitions of recycling.

- Only ten chemical recycling facilities operate in the US. Nearly all are in pilot- or demonstration-stage. None have become commercially successful. Two of these ten are in the Ohio River Valley: Alterra and PureCycle. Several more have been proposed.

- Chemical recycling is financially and technically risky. It is based upon immature technologies and relies on yet-to-emerge supply chains and infrastructure. It faces challenging market dynamics. Recycled plastic must compete with a global oversupply of virgin plastic. The glut of virgin plastic may last for another decade.

- Plastic recycling processes are toxic and dangerous for workers and communities. Out of more than 16,000 chemicals associated with plastic production, at least 4,200 are considered “highly hazardous” to human health and the environment. However, only 980 of these chemicals of concern are regulated globally at this time. Mounting evidence by the scientific community suggests that hazardous chemicals emitted through the chemical recycling processes are extremely toxic for fenceline communities. Deregulating these processes would increase risks for local communities.

- The petrochemical industry has lobbied for chemical recycling to be reclassified and deregulated at the federal and state levels. The EPA currently designates pyrolysis and gasification — the most common forms of chemical recycling — as solid waste incineration, which is strictly controlled under the Clean Air Act. But, due to industry pressure, 25 states now classify these processes as manufacturing facilities, which are less heavily regulated. States, however, must adhere to federal EPA rules. This means pyrolysis and gasification facilities remain subject to the strictest air pollution controls.

- Co-location of chemical recycling facilities will further burden communities already impacted by the petrochemical industry. Existing petrochemical and chemical recycling plants are already located in low-income communities, imposing environmental burdens and injustice. Communities, such as the Ohio River Valley, will become more polluted if chemical recycling facilities are co-located with existing petrochemical facilities.

- The fossil fuel industry expects the growing virgin plastics market to offset declining demand for transport fuel. As the energy transition progresses, virgin plastics have become the industry’s Plan B. The petrochemical/fossil fuel industry has touted chemical recycling as a solution for plastic waste, though it has known for decades that recycling plastic will not solve the plastic pollution problem. This perception has enabled the unbridled growth of virgin plastics.

- Chemical recycling is not a silver bullet to solve the plastic waste pollution problem — far from it. Measures to reduce the production of virgin plastic are required.

- The Ohio River Valley has better options than chemical recycling.