The 2020 election has taken place against the backdrop of a pandemic, a racial justice movement, and record-setting political spending–projected to total nearly $14 billion, a figure greater than the GDP of Armenia. For a culture that is used to immediate gratification, the days spent waiting for election results required more patience and discipline than waiting for FedEx packages back in April. But perhaps aside from the results themselves, the shadow of uncertainty looming largest over this election season has been cast by the volume of actions before our courts. Leading election law scholars like Rick Hasen, Chancellor’s Professor of Law and Public Policy at the University of California, Irvine, have posited that this election will be the most litigated election in American history. If the filings to date are any indication, the volume and significance of these cases could be staggering.

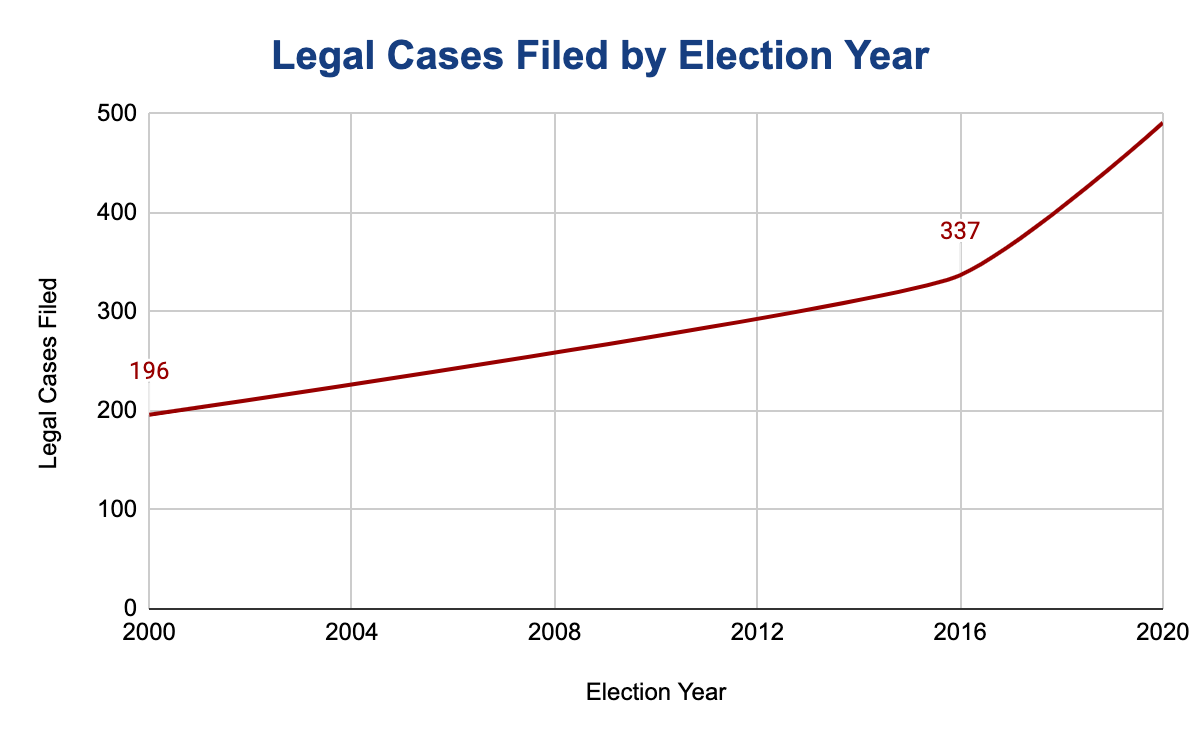

Even before Election Day, 2020 yielded more than double the number of election lawsuits in 2000, a contest that was ultimately decided by Justice Scalia and the Supreme Court of the United States. Accounting for cases filed both before and after the election, the Bush v. Gore era saw 196 election lawsuits, while in 2016, courts handled a total of 337 election-related cases. According to Stanford’s Healthy Elections Tracker, more than 500 cases have already been filed in connection with the 2020 election, with fully 70 of those cases in the Ohio Valley states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Kentucky alone.

As election officials and poll workers put in overtime hours to ensure that every vote is counted, the Trump Campaign, the Republican National Committee, and other Republican candidates for office have challenged how state and county election officials implemented aspects of the state’s new vote-by-mail program. Below, the most significant election-related cases pertaining to Pennsylvania have been distilled into four key questions:

- Did Philadelphia comply with canvassing observer requirements?

An Election Day judge ruled that Philadelphia was complying with canvassing observer requirements, but on appeal by the Trump Campaign a Commonwealth Court judge felt differently and directed the city to allow canvassing observers to watch from a closer distance of six feet. A petition for appeal to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court filed by the City of Philadelphia is pending, but in the meantime canvass observers are allowed to watch from a minimum setback of six feet.

- Did the United States Postal Service fail to deliver some ballots on time?

Given the increased volume of mail-in and absentee ballots in the 2020 election, many voters relied on the United States Postal Service (USPS) to ensure that their votes would be counted. Court-ordered sweeps of USPS facilities, including those in Pennsylvania, did uncover ballots that had not yet been delivered and were delayed in the USPS system.

- Can Pennsylvania count ballots received after 8pm on Election Day?

On September 17, 2020, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court issued an opinion to allow mail-in ballots received up to three days after Election Day to be counted, so long as they were postmarked by 8pm on November 3rd. The case is on appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States, which has not yet agreed to hear the case in full, but did order election officials to segregate and tally separately any ballots received between 8pm on November 3rd and 5pm on November 6th. If the Supreme Court of the United States agrees to take up the case post-election, its decision could prevent the ballots in question from counting in the overall result for the state. Pennsylvania’s top election officials do not anticipate that this will alter the outcome of the election given the low number of ballots of this kind reported by county elections officials.

- Can counties allow voters to fix missing information on the outside of their ballots?

The Montgomery County Board of Elections implemented a process, beginning around October 21, to notify mail-in and absentee ballot voters that there was an error in their voting materials and giving them an opportunity to fix or fill in the necessary information. This is known as a cure process. On Election Day, Republican candidates filed suit in federal court directly challenging the Montgomery County process. The case is still pending, awaiting a ruling on whether the Montgomery County cure process ran afoul of the law, but in the meantime the federal judge hearing the case permitted the previous cured ballots to be counted. Montgomery County’s elections clerk testified that the county had allowed 93 ballots to be cured.

The country is ready to move forward, and although these legal cases and the questions they present have yet to be fully resolved, it is unlikely that the outcomes will change the overall result of the presidential election in Pennsylvania.

Key Election-Related Cases in Pennsylvania: Canvassing Observer Access

On November 3rd, an Election Day judge for the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas issued an order denying the Trump Campaign’s claim that Philadelphia County was not complying with canvassing observer requirements. (Canvassing is the process of reviewing, opening, and counting mail-in and absentee ballots in addition to processing returns from in-person polling locations.) Candidates for office and political parties have the legal right to be in the room where this process is taking place as long as they do not compromise the efficiency of the process, the safety of the workers, voter confidentiality, or ballot security.

The challenge, In Re: Canvassing Observation, No. 7003, was based on a claim by a lawyer for the Trump Campaign who served as a canvassing observer in the City of Philadelphia, at the Philadelphia Convention Center in a room where 350,000 ballots were being counted. This witness was permitted into the room, but alleged as the basis for the lawsuit an inability to read the writing on the outside of the ballots. According to his testimony, he wanted to read the content on the outside of the ballots to identify errors or markings on the envelopes such that he could file specific objections to those ballots.

The Election Day judge found that the role of canvassing watchers is to observe, rather than audit, the ballots and therefore being unable to read the writing on the ballots did not equate to unlawful restriction of access. The Trump Campaign appealed this decision to Commonwealth Court, where Judge Christine Fizzano Cannon reversed the decision, finding that canvassing observers should be allowed closer access. Following Judge Cannon’s opinion, the Trump Campaign declared a “major legal victory” though in practical terms, it is unclear how much more canvassing observers can learn from 6 feet away than they could from 20 feet away. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania accepted a petition by the City of Philadelphia to allow an appeal of the Judge Cannon’s decision, but limited the appeal to three issues, two of which pertain to whether the case is moot.

In Philadelphia, not only did canvassing observers have in-person access, but the City Commissioners provided a livestream of the process on YouTube, making it accessible to anyone with an internet connection. In addition, the Pennsylvania Department of State provided an online dashboard enabling the public to track the progress of absentee and mail-in ballot processing by county.

Key Election-Related Cases in Pennsylvania: USPS and Timely Delivery of Ballots

According to records from the Pennsylvania Department of State, nearly 485,000 mail-in and absentee ballots issued to voters were not returned by Election Day, which amounts to more than ten times the Pennsylvania vote margin between Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton in 2016. According to documents made public via a lawsuit (NAACP v. USPS), two US Postal Service (USPS) processing facilities in Pennsylvania–one in central Pennsylvania and one in Philadelphia–were ordered by Federal Judge Emmet Sullivan to conduct sweeps of their facilities to identify ballots that were potentially still “stuck” in the system.

In Philadelphia, only about 66% of ballots in the USPS system were delivered on time, and the central Pennsylvania facility provided on-time delivery of fewer than 62% of scanned ballots. Multiple USPS facilities outside of Pennsylvania were also in question. The ability of voters to rely on the Postal Service for timely delivery of ballots is of particular importance due to the fact that the vote margin between Donald Trump and Joe Biden has been extremely narrow, and there is still ambiguity about whether late-received ballots will be counted (see discussion below).

Key Election-Related Cases in Pennsylvania: Vote By Mail

Will Ballots Received Late be Counted?

The USPS case outlined above ties into another high profile case–Republican Party of Pennsylvania v. Boockvar–this one pertaining to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision to extend by three days the deadline for receipt of absentee and mail-in ballots. Less than a week away from Tuesday’s election, the Supreme Court of the United States issued an Order in Boockvar stating that the Court would not–at least not at that time–interfere with the decision of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to allow mail-in ballots received up to three days after Election Day, so long as they were postmarked by 8pm on November 3rd. However, Justice Alito emphasized that the petition for certiorari (the legal filing that formally asks the court to hear a case at its discretion) is still under consideration and could be granted post-election. Alito went even further, foreshadowing his opinion that “there is a strong likelihood that the State Supreme Court decision violates the Federal Constitution.”

Putting aside for a moment the significance of Alito’s suggestion that the court may still decide to hear the case at a later date, the practical result of his order in Boockvar was that ballots postmarked (or, if lacking a legible postmark, presumed to have been mailed) by the time the polls closed on November 3rd and received by 5pm on November 6th were to be segregated. The reason for keeping and counting these ballots separately was to provide a clear remedy (the ability to easily identify and discard) in the event that they are later invalidated by the Supreme Court. On October 28th, the same day the Supreme Court issued its order, and again on November 1st, Pennsylvania Secretary of State Boockvar issued guidance clarifying the requirement to segregate and count separately all ballots received after 8pm on November 3rd.

Despite the issuing of this guidance, on November 6th, the Repubican Party of Pennsylvania filed a petition to the Supreme Court asking for a formal order requiring that county boards of election segregate ballots received after Election Day through November 6, 2020, and refrain from counting those ballots while their party’s legal challenge remains pending. The petitioners claimed that the guidance from Secretary Boockvar is not legally binding on the county boards of election, and even if it were binding, they could not confirm that all 67 counties were complying with that guidance. Justice Alito issued an Order requiring the segregation and separate counting of these late-received ballots, which is legally binding on the counties. However, Justice Alito did not order the counties to refrain from counting those ballots, as the Republican Party had requested, so long as those votes were tallied separately. On November 9th, Republican state attorneys general, including that of Ohio, filed in support of the petitioners in the case, asking the Supreme Court of the United States to accept the case and reverse the decision of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

With most outlets calling 290 electoral votes for Joe Biden, even Pennsylvania’s 20 electoral votes (votes that are currently factored into Biden’s lead) may not be necessary for the Democrats to win the presidency. And, it is unlikely that the subset of votes from ballots received after 8pm on Election Day would change the result in Pennsylvania. Even so, if the Supreme Court of the United States does grant the underlying petition to hear the Boockvar case, its ruling and accompanying opinion could have an impact on how future election activities are conducted.

Was Montgomery County’s Process for “Curing” Mail-in and Absentee Ballots Legal?

Montgomery County is located in southeastern Pennsylvania, abutting Philadelphia. It is the third most populated county in the state and is home to roughly 580,000 registered voters, of which about 50% are registered Democrats and 35% are registered Republicans. According to the Pennsylvania Department of State, in the 2020 general election, 243,740 votes were cast in Montgomery County via absentee or mail-in ballots. Election Day votes cast showed Donald Trump with a 26,675 vote lead over Joe Biden, but with 98.5% of all mail-in and absentee votes counted, Joe Biden now leads the county by 130,636 votes.

Pennsylvania voters submitting their ballots by mail must fill out their ballot, fold and seal it into a secrecy envelope, and then fold and seal that stuffed secrecy envelope into an outer return envelope (also known as a voter declaration envelope because it requires the voter to sign beneath a pre-printed declaration). In some cases, the outer “voter declaration” envelope was missing information, such as the full address of the voter, so the Montgomery County Board of Elections aimed to provide what is sometimes known as a “cure process.” A cure process gives voters an opportunity to “cure,” or fix, their submission by filling in information that may have been omitted in their initial submission. Two separate lawsuits have been filed that appear to attack a cure process that the Montgomery County Board of Elections implemented, beginning around October 21, to notify mail-in and absentee ballot voters that there was an error in their voting materials. Montgomery County’s elections clerk testified that the county had allowed 93 ballots to be cured.

On Election Day, Republican candidates filed suit in federal court directly challenging the Montgomery County process, in a lawsuit referred to as Barnette (Barnette, et al. v. Lawrence, et al.; see also the related case Donald J. Trump for President v. Montgomery Cty. Bd. of Elections). The timing of the suit, coming after many voters had already returned their ballots, meant that the court’s invalidation of the County’s process would potentially disenfranchise voters. If the suit had been filed much earlier–nearer to when the County began implementing the process–voters who had followed the County’s procedures may still have been able to vote provisionally. On November 4th, U.S. District Judge Timothy Savage presided over Barnette, expressing skepticism over whether the integrity of the election was compromised by the curing procedure employed by Montgomery County, and refused to order the county to toss ballots that had previously been cured. On November 11th, the plaintiffs were granted a voluntary dismissal.

Conclusion

Although the Montgomery County case regarding the validity of ballots that had been “cured” was voluntarily dismissed, much of the election-related litigation of significance filed in connection with Pennsylvania is still working its way through the courts. We may not have final rulings on these cases for days, weeks, or even months, but even then it is very unlikely that the overall result of the presidential election will change. We will continue to track key developments in these and other related matters (like the Trump Campaign’s difficulty retaining legal representation for a lawsuit filed in federal court in Pennsylvania challenging the validity of the state’s election), because even if the results of this election are not impacted, they could determine how we conduct future election activities.

Lauren M. Williams, Esq., Owner and Head Counsel at Greenworks Law and Consulting, LLC, contributed to this post.