Several weeks ago, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) released their plan for “Preserving Coal Country” amid national policy efforts to address climate change and regrow the economy with large-scale infrastructure investments. The UMWA plan listed several policy proposals to help coal mining communities, including a ‘true transition’ for coal miners that have lost their jobs as the country has moved toward cleaner energy. This included wage replacement, health and pension coverage, tuition assistance and workforce training and certification, and other investments.

While it is unclear if federal climate change and infrastructure legislation will include these proposed transition investments, states like West Virginia could do something similar to help struggling coalfield communities and workers who are dislocated by the shifting economy. This could build on other federal efforts to revitalize coal communities. One way to do this would be to scale back or eliminate the state’s tax subsidy for thin-seam coal production and direct these funds to a coal worker dislocation and revitalization fund.

The Thin-Seam Severance Tax and Metallurgical Coal

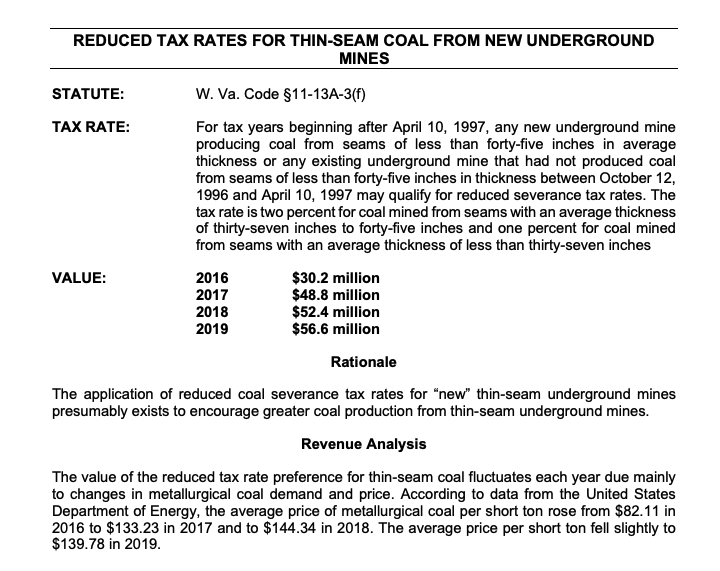

Since 1997, any new underground coal mine in West Virginia that extracts coal from seams less than 45 inches qualifies for a reduced severance tax rate. While the statutory severance tax rate is 5 percent, the rate for coal mined from seams between 37 and 45 inches is 2 percent and 1 percent for coal mined from seams less than 37 inches. It is widely understood that most—if not all—of the coal being mined at these reduced rates is metallurgical coal.

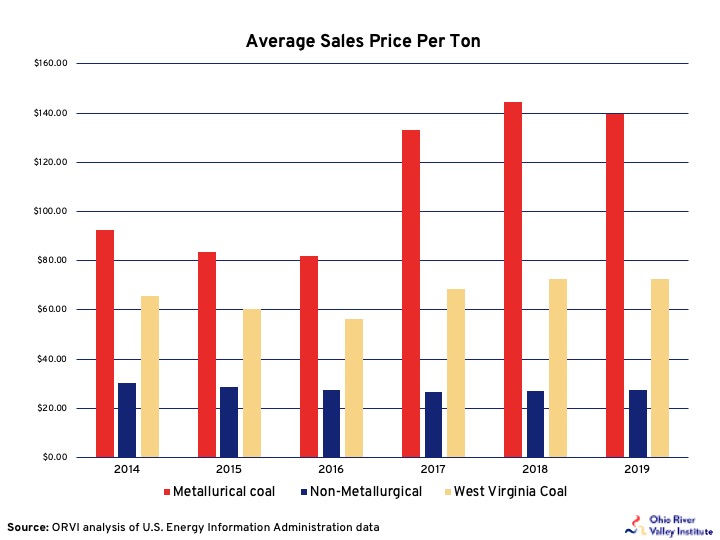

Metallurgical coal, or coking coal, is premium bituminous coal with a high carbon content that is used in the process of creating coke to make steel. It typically sells at a much higher price than the thermal coal used to produce electricity. Metallurgical coal, which is often referred to as “met coal”, has seen a lot of volatility in prices over the last few years, increasing by 70 percent from 2016 to 2019, from $82 to $140 per ton. As the chart below shows, the price for a ton of met coal is typically three to five times higher than non-met coal. While met coal prices by state are unavailable, the average sales price of coal in West Virginia was $73 per ton in 2019, which includes both met and non-met coal. Currently, the price of met coal is around $160 per ton.

According to the West Virginia State Tax Department, the value of the thin-seam severance tax reduction was between $30 and $57 million from 2016 to 2019. In other words, seam coal producers paid $57 million less in coal severance taxes because of this subsidy. The value of the tax preference was over $70 million in 2010, making up 15 percent of coal severance tax collections. In 2019, it made up 23 percent of the state’s $250 million in coal severance tax collections. This highlights that met coal is also a growing share of the state’s coal economy.

Back in 2006, the state recommended a review of the reduced rate on thin-seam coal production to see if there was a production cost difference “between a conventional coal mine taxed at 5 percent and thin-seam mines taxed at 2 percent or 1 percent under the regular severance tax, to determine whether the tax preference accurately accounts for such differences.” In 2017 and 2020, West Virginia Governor Jim Justice proposed creating tiered severance tax rates for metallurgical and steam coal based on coal prices per ton. The proposal included severance tax rates ranging from 3.5 percent to 10 percent based on the price of met coal per ton.

More recently, Governor Justice proposed increasing the thin-seam coal severance tax by establishing tiered rates based on price per ton. It was estimated to increase coal severance tax revenues by $7.5 million. Governor Justice has also stated that “[t]here’s no way that anybody’s (coal companies) cost is going to be greater than $80 (a ton).” Others have also called for eliminating or scaling back the thin-seam coal severance tax subsidy.

Met Coal Production in West Virginia

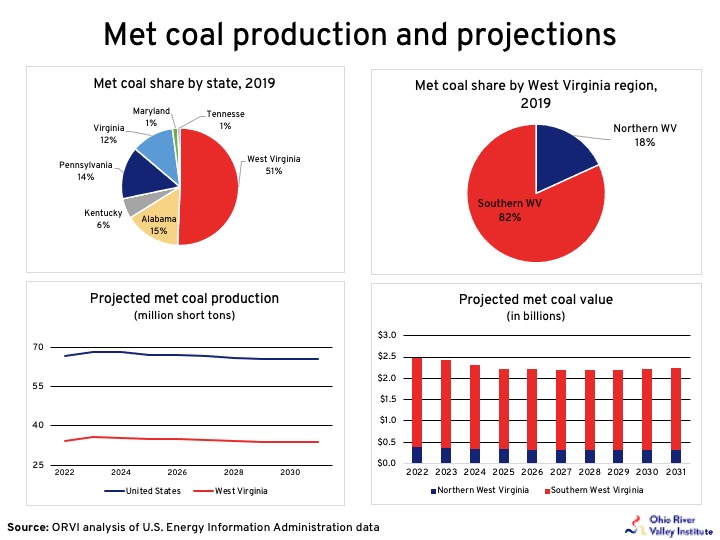

Metallurgical coal production data by state is limited. Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) shows that the United States produced 70.7 million tons of met coal in 2019. Of this amount, only 53.1 million tons is assigned to the state where it was extracted and sold. Using the subtotal of 53.1 million tons of met coal, West Virginia produced 51 percent, or nearly 27 million tons, of met coal in 2019. Alabama was the second largest met coal producer, followed by Pennsylvania and Virginia.

A majority of the met coal produced in West Virginia is produced in the southern part of the state, where the average sales price for coal was $91 per ton in 2019, compared to just $55 per ton in northern West Virginia, where most of the coal is used for electricity production. The average price per ton was highest in Greenbrier ($128), Raleigh ($125), Wyoming ($108), and McDowell ($105) counties, which are all located in southern West Virginia.

According to the West Virginia Coal Association, West Virginia produced 35.4 million tons of met coal in 2018, with 86 percent coming from the southern coalfields of the state. EIA data also shows that 86 percent of the 27.6 million tons of met coal sold from West Virginia was from southern West Virginia in 2018, but 82 percent in 2019.

About 75 percent of met coal mined in the United States is exported, and the rest is sent to coal plants domestically for industrial uses (e.g., steel making). In West Virginia, approximately 38 percent of coal in 2019 was exported. In southern West Virginia, that share was 52 percent, compared to 21 percent in northern West Virginia, highlighting (again) that most of the coal in southern West Virginia is met coal.

While thermal (steam) coal production will continue to decline in the United States as corporations, utilities, and governments move to cleaner electricity production, met coal will likely continue to be produced until steel producers find cost-effective alternatives. Approximately 70 percent of global steel production relies on met coal, and the steel industry is the highest emitter of CO2 emissions among heavy industries at 10 percent of global energy sector CO2 emissions. Some steel companies are already moving to fossil-free steel by using renewable “green” hydrogen, but it will likely take at least another decade before it is cost competitive with met coal. Also, demand for met coal could increase if a large-scale federal infrastructure package is passed that requires American-made steel. In other words, now is the time to ensure that the coal industry pays its fair share and contributes to ensuring coal miners are not left in the dust.

Establishing a Coal Trust Fund for Dislocated Workers

EIA projects that met coal production will average 67 million tons between 2022 and 2031, with an average price of around $72 dollars per ton. Northern Appalachia is expected to produce about 15 million tons of met coal over this period, while central Appalachia is expected to produce an average of 41 million tons. Using West Virginia’s share of northern and central Appalachian met coal production in 2019, West Virginia is expected to produce about 35 million tons of met coal per year over the next ten years. Applying projected met coal prices to these figures shows that total met coal production value in West Virginia will average about $2.3 billion per year.

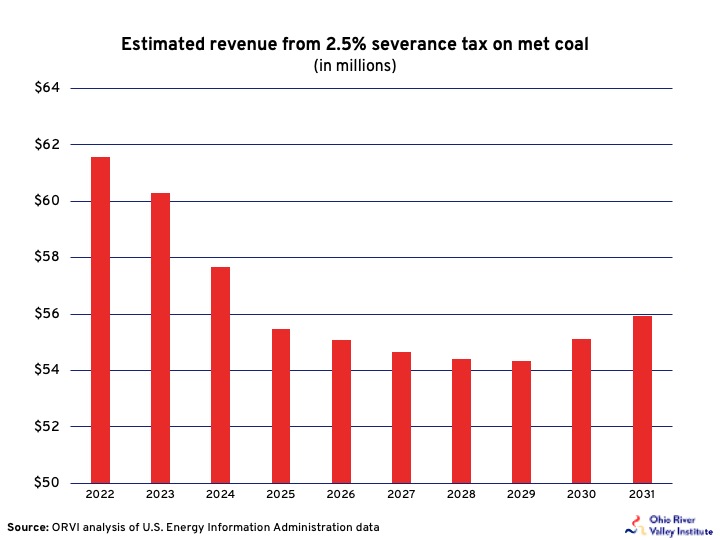

Applying a 2.5 percent severance tax to the estimated value of met coal production would yield approximately $56 million per year, which is roughly equivalent to the value of the thin-seam subsidy in 2019. However, the amount of revenue would be highly volatile as past price fluctuations for met coal have shown. In addition, West Virginia lawmakers could adopt tiered rates for thin-seam coal production or eliminate the subsidy and apply a higher severance tax rate on met coal to reach a desired revenue target.

The revenue from removing the thin-seam severance tax subsidy could be deposited into a trust fund where the monies would be used to assist coal miners who have lost their jobs and benefits. Specifically, this could include pension and health benefits, guaranteed re-employment in jobs such as reclamation, income support through wage insurance (pays the difference between compensation in coal job and current job), retraining support (apprenticeship or community college), and relocation allowances. A recent analysis of providing these supports to fossil fuel workers in West Virginia estimates the cost at $126,000 per worker over three years, or $42,000 per year. With a projected revenue of around $56 million per year, eliminating the thin-seam subsidy could provide assistance to approximately 1,300 coal workers per year. Other ideas could include providing extended unemployment insurance similar to the pandemic unemployment assistance, or using the funds to directly employ former coal miners in public sector jobs or provide educational benefits to family members. Another model would be the Coal Workforce Transition Program in Alberta, Canada.

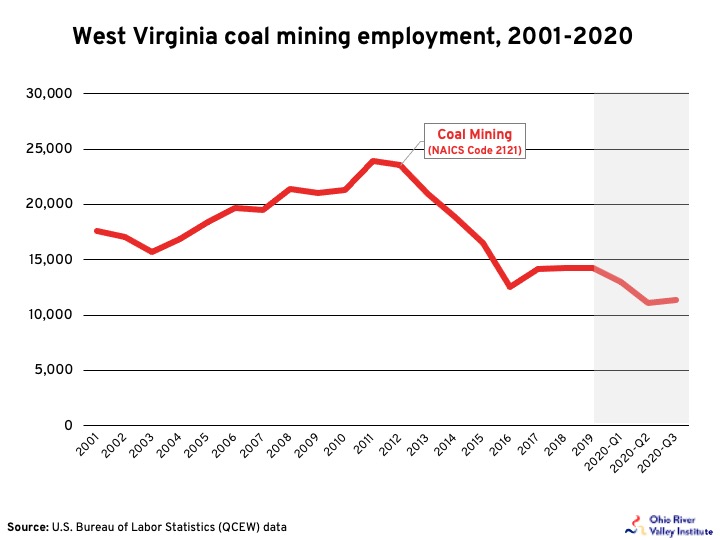

Coal mining employment in West Virginia has declined by over 12,500 since 2011 and has dropped by about 2,500 since the COVID-19 pandemic. As of the 3rd quarter of 2020, there were 11,324 people directly employed by the coal mining industry. A portion of these workers—perhaps 23 percent—are not hourly workers but are management, supervisors, engineers, foremen, office workers, and salespeople. These workers may not need assistance since they are not hourly paid coal miners.

It is unclear what the potential impact federal climate legislation or actions by other states could have on coal mining employment in the state. While coal miners at thermal coal mines will be more impacted by actions taken to reduce fossil fuel electricity, global economic conditions are more likely to impact demand for met coal in the state.

West Virginia would not be the first state to create a trust fund from coal severance tax revenues. While other states use severance tax trust funds to invest in education, economic development, infrastructure, and other things, West Virginia never managed to fund its severance tax trust fund (Future Fund) in order to provide a softer landing from the booms and busts of the energy industry. This may be West Virginia’s last opportunity to do so and to ensure coal workers have what they need to get new jobs and take care of their families.