How the greater Ohio Valley can awaken from its natural gas and petrochemical fever dream to an economic future that actually delivers jobs and prosperity

“Game-changer” – It’s amazing the word doesn’t stick in their throats.

For a decade, policymakers in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia have been calling the natural gas fracking boom and, more recently, the petrochemical and plastics industries, economic game-changers. But, even as fracking pads and pipelines run riot over the landscape and what many regard as the high cathedral petrochemical prosperity – the Royal Dutch Shell ethane cracker in Monaca, Pennsylvania – rises along the headwaters of the Ohio River, the region’s economic game is anything but changed. in fact, the most striking feature of the economies of the Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia is how relentlessly unchanged those economies are as compared to their condition before visions of Texas-like gas fields and Gulf Coast-like petrochemical clusters began dancing in regional leaders’ heads.

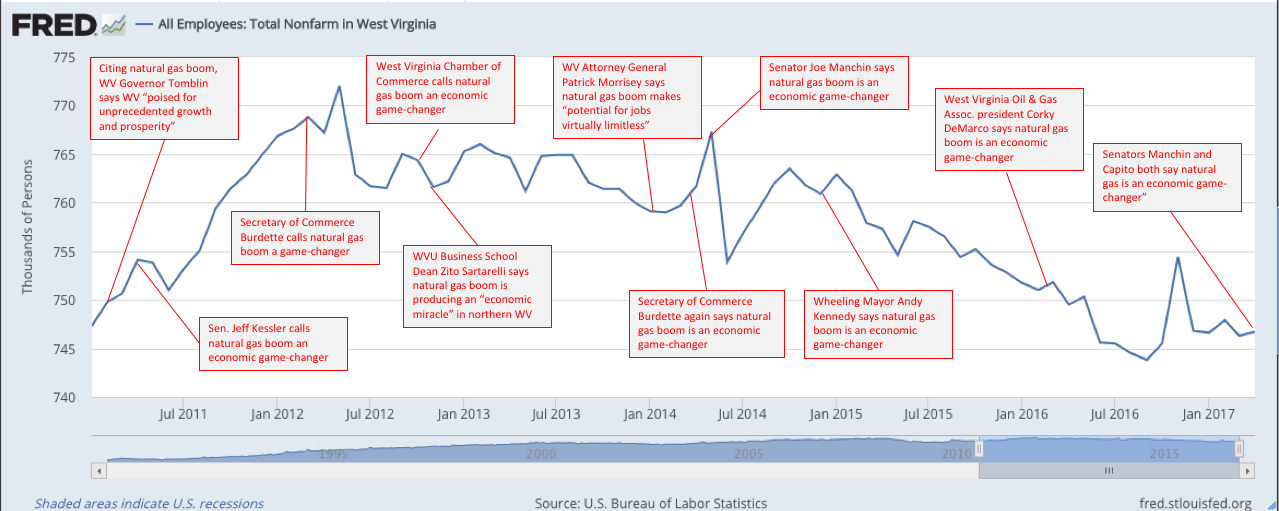

That’s why in West Virginia, the phrase “game changer” has become something of a joke and inspired this 2017 graphic that appeared in “The State of My State” blog[1] illustrating the state’s loss of jobs even as leaders and policymakers were hailing the natural gas boom as, in the words of one, “an economic miracle”.

From early 2011 to mid-2017, West Virginia political leaders repeatedly asserted that the fracking boom was an economic game-changer even as jobs evaporated to the point that West Virginia literally had no more jobs at the end of the fracking boom than it had at the beginning. Meanwhile, Senator Shelley Moore Capito was already on to yet another “game-changer”.

West Virginia policymakers and business leaders weren’t the only ones seduced. Ohio Governors John Kasich and Mike DeWine and Pennsylvania Governors Tom Corbett and Tom Wolf all joined the game changer chorus along with a long list of industry-related groups ranging from the American Petroleum Institute and the American Chemistry Council to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

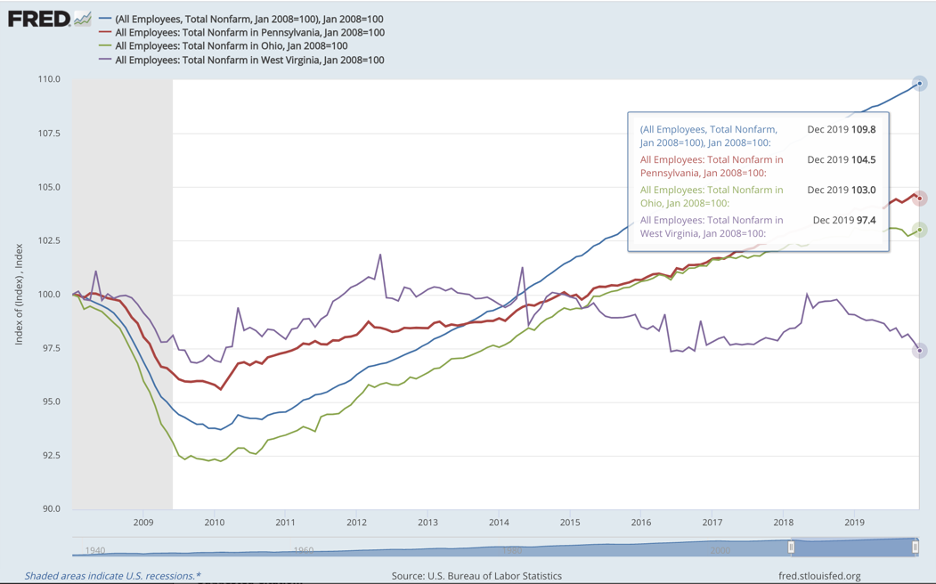

But, for all the hyperbolic claims, starting with former West Virginia Governor Earl Ray Tomblin declaring in 2011 that his state was “poised for unprecedented growth and prosperity”, the economic reality is one of continued stagnation and, in many places, deterioration — conditions that have persisted for decades. That’s reflected in the fact that Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia have lagged far behind the nation in job growth since the dawn of the fracking boom.

From the beginning of the Great Recession to the end of 2019 and prior to the coronavirus crisis, Ohio and Pennsylvania have seen less than half the level of job growth as the nation as a whole and West Virginia has experienced an absolute decline in employment.

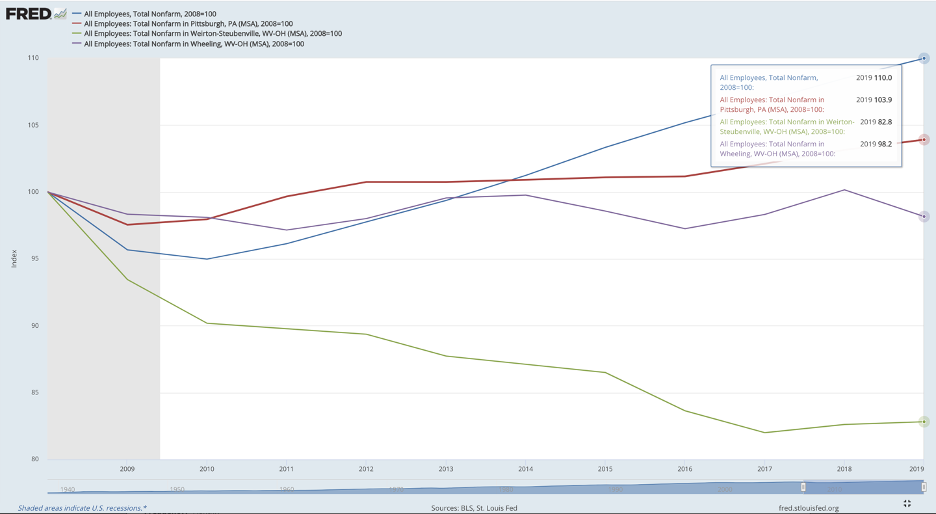

More disconcerting is the fact that, when you drill down from the state level the region’s major metropolitan areas, the picture is even worse.

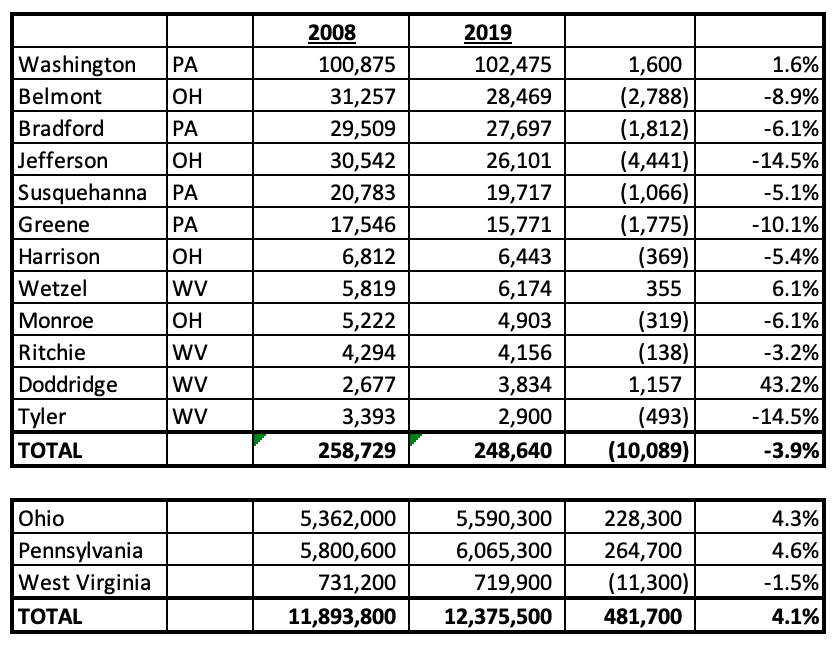

The major natural gas regions in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia counties are actually an economic drag on their respective states. And, within the natural gas regions, the metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) that are most dependent on the natural gas and petrochemical industries – Weirton/Steubenville and Wheeling/Belmont County – are taking the worst beating. Meanwhile, the Pittsburgh MSA, which is the most economically diverse and least dependent on natural gas and petrochemicals, is the least poorly performing.

It’s also worth pointing out that natural gas and petrochemical job growth in the Ohio Valley is not being masked or offset by the region’s loss of coal mining jobs. West Virginia’s Ohio and Marshall Counties, which with Ohio’s Belmont County comprise the Wheeling MSA, actually saw the number of coal mining jobs increase from 1,325 in 2009 to 1,798 in 2019. Statistics were not available for current coal mining employment figure for Belmont County, Ohio, where the industry is still quite active. But, even had Belmont County lost all of the 764 coal mining jobs it had in 2009, the net coal mining job loss for the Wheeling/Belmont County MSA could not be more than 300 jobs, not enough to significantly alter the statistical picture of an area that at the end of 2019 had over 65,000 employed people[2].

Investors are suffering too

As bad as the jobs picture is, investors in the Appalachian fracking boom may have done even worse. A recent report from the Institute for Energy Economic Financial analysis showed that, in the last decade, just eight of Appalachia’s largest producers collectively spent $73.4 billion dollars more on drilling and other capital expenditures than they earned in sales of natural gas. IEEFA also reports that at least eleven natural gas exploration and development companies in Appalachia have filed for bankruptcy protection. Newest to the list and most prominent is Chesapeake Energy whose then CEO Aubrey McLendon was the principal evangelist and face of the fracking boom before he was eventually indicted for investor fraud. Carnage within the industry may not be over as the nine largest remaining companies continue to bear over $30 billion in accumulated debt at a time when rock bottom prices for natural are forcing them to continue incurring operating losses.

In short, the natural gas fracking boom – the region’s original economic “game-changer” – has been anything but. Despite the fact that gas is being produced in prodigious volumes that outstrip even the most optimistic projections of a decade ago by 50%[3] job growth is weak to non-existent. So, in the wake of more than a decade of failure to deliver on promised job growth, proponents are attaching their grandiose claims to a new rising star – the petrochemical and plastics industries.

The latest economic “game changer”: The Shale Crescent

Given the success that promoters of the fracking boom had in winning a grab-bag of legal and regulatory favors and financial incentives from state legislators, it’s not surprising that petrochemical and plastics evangelists seem to be running the same game plan starting with an industry-sponsored study that promises more than 100,000 new jobs.

Given the success that promoters of the fracking boom had in winning a grab-bag of legal and regulatory favors and financial incentives from state legislators, it’s not surprising that petrochemical and plastics evangelists seem to be running the same game plan starting with an industry-sponsored study that promises more than 100,000 new jobs.

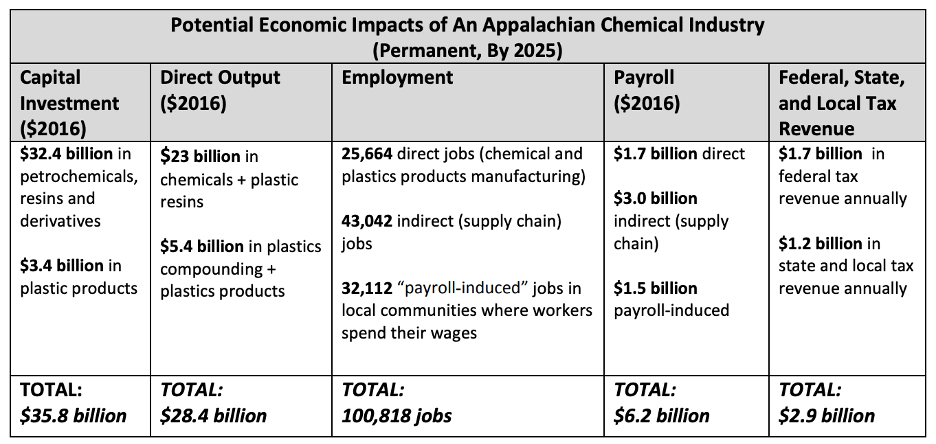

In May 2017 the American Chemistry Council issued a report titled “The Potential Economic Benefits of an Appalachian Petrochemical Industry”. The first section of the report’s executive summary is appropriately titled, “Shale Gas – A Game Changer for U.S. Competitiveness”. The report goes on to argue that the natural gas resources in the Marcellus, Utica, and Rodgersville formations are sufficient to support as many as six ethane cracker plants around which there should be arrayed an assortment of fractionators and processing plants, 500 miles of new pipeline running the length of the upper Ohio River valley, and a significant amount of natural gas liquids storage capacity. And, around this cluster of petrochemical infrastructure, there would grow up vastly expanded manufacturing industries, principally in plastics. We are told that the Shale Crescent could eventually rival the massive Gulf Coast as a petrochemical hub bringing with it tens of billions of dollars in investment and just over 100,000 “permanent” new jobs, not counting many thousands of temporary jobs in construction and related fields that would be required to build out this massive array by the year 2025.

Source: Page 4, “The Potential Economic Benefits of an Appalachian Petrochemical Industry”, https://www.americanchemistry.com/Appalachian-Petrochem-Study/

The suggestion that so extensive a build out could happen in the eight years following the report’s publication has already proven to be exaggerated. But, at the time the petrochemical industry and its proponents were giddy with enthusiasm. The report repeatedly claims that, “To date, four crackers (with a combined capacity of 4.0 million metric tons) have been announced.”

This is an apparent allusion to the Royal Dutch Shell cracker project in Monaca, Pennsylvania; the Odebrecht/Braskem project in Wood County, West Virginia; the PTTGC project in Belmont County, Ohio, and either an Exxon/Mobil project for which no site had yet been identified or an Appalachian Resins, Inc. “baby cracker” project in Monroe County, Ohio. The problem is that “announced” was too strong a claim, because only one of the aforementioned projects, the Shell cracker, was the only one that at the time had received a favorable final investment decision. As for the others, the Odebrecht/Braskem and Appalachian Resins projects were canceled, the PTTGC project had its final investment decision delayed and today continues to be delayed, and the Exxon/Mobil project never did identify a location. In the aftermath of the recent meltdown of the economy and oil markets, it is widely presumed to be off the table. And, because the crackers aren’t being built, few of the facilities that were expected to rise up around them haven’t been built either. In fact, in the more than three years since Shell announced its decision to proceed with the cracker in Monaca, no other major petrochemical investment planned has been green-lighted in the region.

The reality behind the grandiose claims

In fairness to the authors of the American Chemistry Council study, their study did not actually predict that the crackers and other facilities would be built. Rather, they were merely analyzing the probable economic impacts, if they were built. But, even that is a fraught enterprise. To understand why, we need only look back at the American Petroleum Institute study that kicked off the natural gas fracking boom.

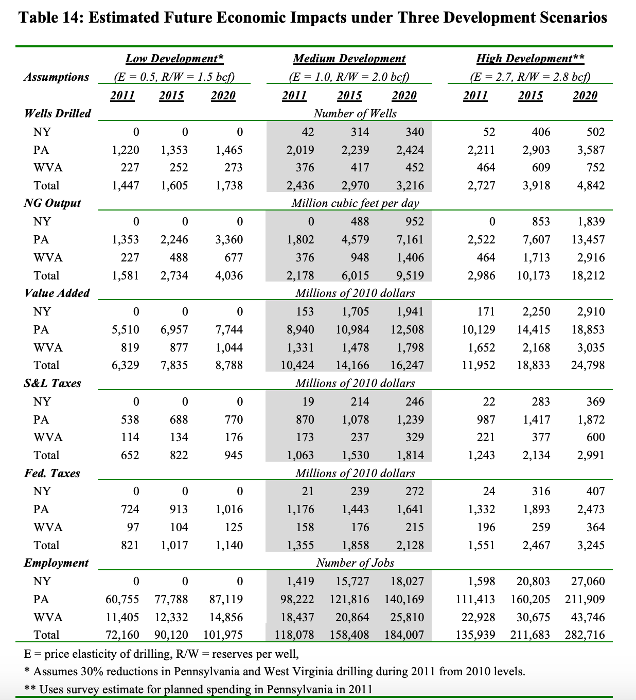

Much like the American Chemistry Council study, the API study, authored by Timothy J. Considine, found that a high level of natural gas production would yield immense numbers of new jobs – in the case of the fracking boom more than 250,000 in just the states of Pennsylvania and West Virginia by the year 2020.

Page 34, “The Economic Impacts of the Marcellus Shale: Implications for New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia”

But, unlike the ACC study, the premise of the API study – a sextupling of natural gas production volume between 2009 and 2020 – actually did come to pass. In fact, it was vastly exceeded. At the beginning of 2020, the region was already producing over 23 billion cubic feet per day, 45 percent more than even the “High Development” scenario contemplated in the API study. One would, therefore, think that the number of jobs created would, if anything, be greater than the numbers predicted.

But, that is certainly not what happened in West Virginia, which was predicted to see 43,476 new jobs. That many jobs would have been numerically sufficient to employ nearly every unemployed person in the state. It’s a figure that’s also four times greater than all the coal mining jobs lost in West Virginia in that same span.

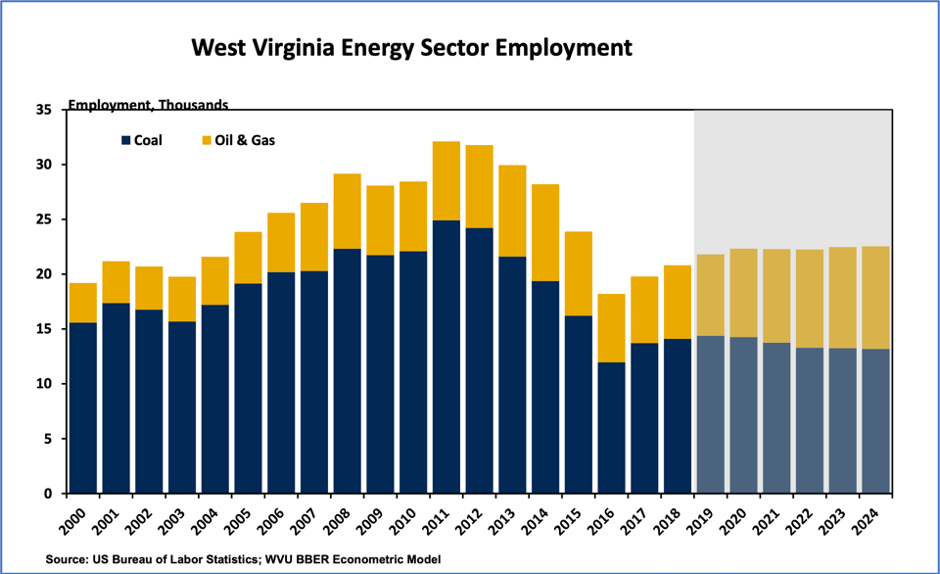

But, between 2008, at the dawn of the fracking boom, and 2018, West Virginia saw direct employment growth of less than 1,000 in the oil and gas sector.

In Pennsylvania the picture is somewhat less grim, but still disappointing. In 2013, former Governor Tom Corbett’s administration claimed that 250,000 people worked in the state’s oil and gas industry. But in 2016, an analysis by the administration of newly installed governor, Tom Wolf found only 29,826 people directly employed by the industry and that, even when indirect and induced jobs were counted, total employment came to only about 80,000[4]. Moreover, many of those jobs existed before the fracking boom, which means that only a small fraction of the 212,000 new jobs predicted by the API study were ever realized.

But, most damning is this recent summary of the number of persons employed in the leading natural gas producing counties of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

While in aggregate the three states saw a 4% increase in employment, the four counties in each that are the largest producers of natural gas experienced a nearly 4% decline in the number of persons employed, making them, as was noted earlier, drags on economic growth rather than contributors to it.

The reasons for the API study’s exaggerated claims are easy enough to identify in hindsight and many should have been known in advance. Among other errors, the study overestimated by two to three times the market price of natural gas and, therefore, the resulting royalties and tax revenues that were expected to trigger indirect and induced job creation. It also naively assumed that all royalty payments would go to local property owners and that those royalty payments would be spent locally within a year of their receipt. The study’s assumptions about the share of goods and services that industry facilities would purchase from in-region suppliers were also questionable. And the study’s assumption of the number of workers that would be required per natural gas well was greatly exaggerated.

These kinds of flaws, aren’t uncommon in industry-funded analyses, which should give leaders and policymakers pause when the feel the urge to repeat findings from the American Chemistry Council about job growth. For instance, the study finds that 25,664 people would be directly employed by petrochemical and plastics manufacturing businesses over and above the number already working in those industries. However, the portion of those jobs provided by petrochemical facilities would seem to be quite small since even the Shell cracker, which is expected to be as large or larger than the four other crackers assumed by the study, will, according to Shell, provide only 600 full-time jobs when it is complete.

Consequently, we can assume that the five crackers will provide at most 3,000 jobs or only a little over 10% of the claimed direct employment figure. And, since processing plants and pipelines are relatively non-labor intensive, we must assume the bulk of the nearly 23,000 jobs will arise in the manufacturing of plastics and substances.

But, according to the study[5], only 10% of cracker output is expected to be consumed in the region. And, as a 2018 U.S. Department of Energy study[6] points out, much of the 10% would not be used to increase manufacturing production, but would instead merely replace supplies currently shipped into the region by suppliers along the Gulf Coast.

For that reason, it’s not obvious that the construction of petrochemical facilities, even if it eventually happens, will result in a corresponding expansion of plastics manufacturing and jobs in the region. And, as we have seen with the fracking boom experience, when an industry fails to hit its marks for direct employment, indirect and induced job projections are rendered moot. Of greater concern, however, is that the buildout will likely not happen at all or will occur on a scale far smaller than the one imagined in the ACC study.

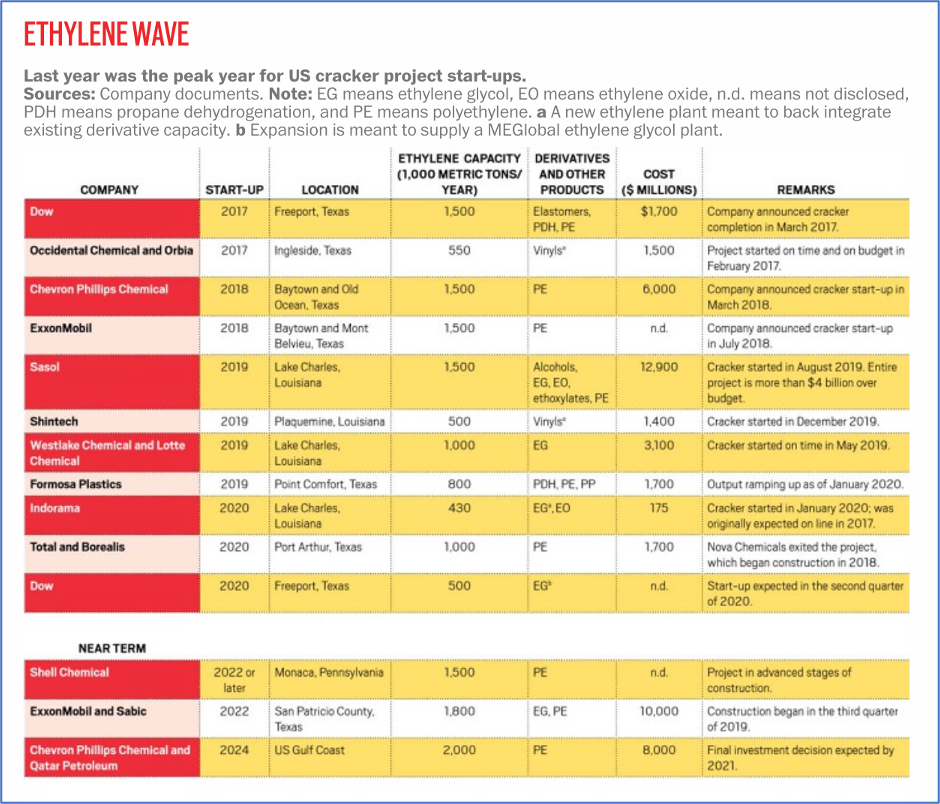

As was mentioned a moment ago, more than three years have now passed since the one and, so far, only major petrochemical project in the Shale Crescent received a positive final investment decision. The drought is not because oil and petrochemical companies haven’t been investing in new facilities. In the three years prior to the onset of the coronavirus crisis ethane cracker capacity in the U.S. expanded by over 50% almost entirely along the Gulf Coast. The building burst has been so great that it has created a situation in which, for the first time, polyethylene manufacturing capacity is greater than demand – a situation that industry analysts now see as continuing from six to as many as ten years into the future. And in Asia, where 80% of all new growth in the plastics market is expected to arise, the expansion of capacity is even larger.

The principal result of this condition of overcapacity is that prices and margins for ethylene and polyethylene production have been in long-term decline. The profit margin for ethane crackers producing polyethylene had dropped from over $1,100 per ton at the beginning of 2018 to less than $600 per ton by the end of last year. That was prior to the current crisis in the economy and oil markets, which have further worsened conditions. At the same time, the competitive cost advantage that ethane has traditionally held over petrochemicals derived from oil has greatly narrowed and, for a brief time in May, was lost altogether.

In summary, growing competition, shrunken prices and margins for polyethylene, and concerns about economic recovery and future growth mean that the economic outlook for major petrochemical projects in the Shale Crescent is at its worst point since the beginning of the fracking boom. These are the reasons why the region has seen repeated delays and cancellations of proposed Appalachian crackers as well as the inability of the sponsors of the proposed Appalachian Storage Hub to find investors.

Under these conditions, it’s unlikely that the large buildout of petrochemical projects imagined in the American Chemistry Council study will take place and, to the degree any buildout does arise, it’s unlikely to be of a type or scale that will lead to major downstream job creation.

Lessons unlearned: Throwing good money after bad

Neither the failure of the natural gas industry to deliver promised jobs and prosperity nor the bad and worsening economic conditions crippling petrochemical expansion seems to be dampening enthusiasm among Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia policymakers who continue predicating the region’s economic development on imagined booms. If anything, they’re doubling down on commitments to fossil fuel-driven development.

In Ohio, the legislature recently renewed an expiring air quality permit for the proposed Belmont County cracker without so that the project’s sponsors can avoid doing a new analysis to determine whether the plant’s emissions will conform to federal requirements. And last year the Ohio legislature passed and Governor Mike DeWine signed into law a bill that Vox energy columnist, David Roberts, describes as “the worst energy bill of the 21st century”.

HB 6’s principal provisions include the bailout of two unprofitable (although the utility, First Energy, won’t tell us how unprofitable) nuclear power plants at the cost of gutting the state’s energy efficiency efforts. Although there is a case to be made for extending the life of some unprofitable nuclear power plants until the energy they provide can be replaced by clean, renewable resources, this is the worst possible way to do it and will cost Ohioans money. At the same time that it bails our nuclear at the expense of energy efficiency, HB 6 also waters down the state’s renewable portfolio standard to a point that, as Roberts describes it, effectively nullifies any incentive for new renewable energy development in the state.

Pennsylvania was an early leader in the establishment of renewable portfolio and energy efficiency standards for it electric system. But, the emphasis put on natural gas development by current Democratic Governor Tom Wolf and his predecessor, Republican Tom Corbett, is greatly expanding that fuel’s share of the state’s generating portfolio. And, while the expansion is coming somewhat at the expense of coal, it is also crowding out new renewable resources to the point that the Pennsylvania utilities may not meet the state’s requirement that they acquire a minimum of 18% of their resources from renewables by 2021.

Meanwhile, in 2015, West Virginia became the first state in the nation to repeal its very modest renewable portfolio standard and the state offers no incentives for energy efficiency. As a result, West Virginia’s electric system is the nation’s most carbon-intensive, getting 92% of the electricity it generates from coal. Not coincidentally, West Virginia also has the fastest rising electric rates in the nation.

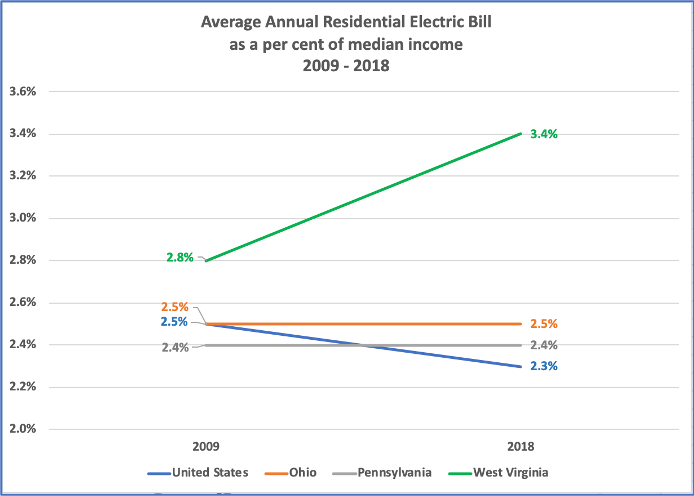

The effects of these policies work to the detriment of climate, but also the pocketbooks of the states’ residents. Despite the supposed cost-effectiveness of natural gas as an electricity resource, the average annual residential electricity bill is rising faster than the national average in all three states.

In West Virginia, the situation is especially dire as the state’s dependence on coal as an electricity resource and extreme energy inefficiency have over the last decade caused electric bills to from being among the nation’s lowest to among the highest. The problem is especially problematic in light of the fact that West Virginia’s median household income is significantly lower than the national average. Consequently, electricity consumes 44% more of West Virginians’ incomes than it does the incomes of all Americans.

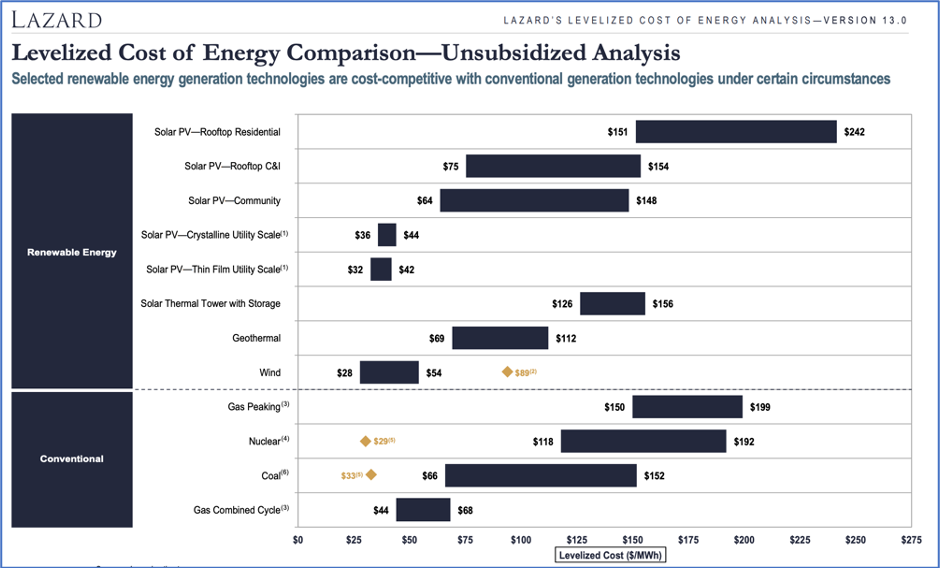

Unless there are changes made to energy policies in the three states, these troubling trends are likely to worsen. While natural gas-fired electricity is relatively inexpensive now, renewable resources including wind and utility scale solar are now cheaper.

And, unlike natural gas, they are not susceptible to possible fuel cost increases that may come about either as the result of market forces or in the event that the federal or state governments begin to adopt carbon pricing policies in response to the growing urgency of fighting climate change. That’s why, when we look ahead a decade or two, by far the most beneficial energy policy for customers is the embrace of renewable resources and energy efficiency. And, as we shall see, it’s also the most promising for jobs and economic prosperity.

An alternative vision for creating jobs and prosperity

Often the debate over natural gas and petrochemical development is characterized as case of “jobs vs. the environment”. But, that’s only half true. Both industries do grievous damage to air and water while also exacerbating global warming. But, as we have seen, they are not great stimulators of jobs and economic prosperity. On the other hand, America’s emerging clean energy economy is.

Economic development is a multifaceted undertaking that in the greater Ohio Valley requires policies that will raise peoples’ incomes and investments in education, healthcare, and infrastructure. But inevitably, economic development also involves the nurturing of industries and businesses that have the potential to thrive and, by doing so, provide jobs and opportunity. So, one of the questions with which governments must grapple is, which industries?

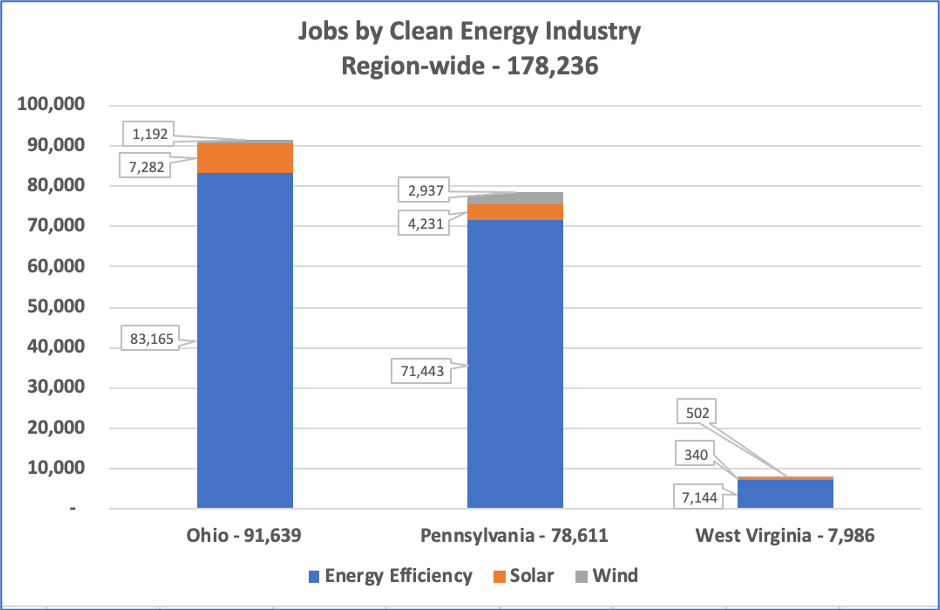

Ideally, we would like the industries that take root in our communities to be growing, non-polluting, and capable of offering good-paying jobs up and down the skills ladder. And we would like jobs to arise not in one town or just a few towns, but in many towns, large and small, around the region. At present, the clean energy sector, including wind power, solar power, grid modernization, and most importantly energy efficiency is one of the few that fulfill all of those criteria.

To begin with, the clean energy economy already provides far more jobs in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia than do natural gas and petrochemicals. According to the USEER Energy Employment by State 2020 analysis, the region’s clean energy economy directly employs over 178,000 workers, which means that economic development strategies targeting clean energy would build on a strong foundation of already established employers who would see their business opportunities expand.

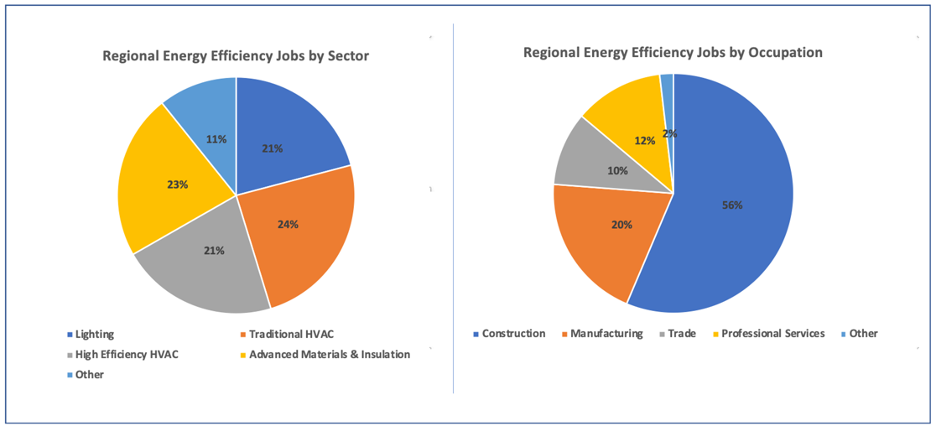

More than 80% of clean energy jobs are in the energy efficiency category in the fields of lighting, HVAC, materials manufacturing, construction, and insulation. The following charts illustrate the business sectors that would grow – lighting, HVAC, materials manufacturing and selling, and insulation – and the occupations that would expand – construction, manufacturing, trade, and professional services.

Rather than chasing and begging out-of-state corporations to come to the region, policymakers would invest in building on and expand those it already has. And by strengthening local economies generally, the greater Ohio Valley would be better able to attract new businesses and employers as well.

That has, for instance, been the case in New York state, which is often ridiculed for resisting fracking, but which at the same time has made significant investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency. As a result, New York’s clean energy economy was growing more than twice as fast as the rest of the state’s economy prior to the recent economic crisis. It’s quite a different picture than in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia where the metropolitan areas most invested in fossil fuels and petrochemicals have been a drag on their states’ economies.

Finally, investments in the clean energy economy yield important benefits other than jobs. Homes and buildings are made more energy efficient, which reduces utility bills and increases the purchasing power of residents. And, by reducing the need for energy, they also reduce air and water pollution as well as greenhouse gas emissions.

These benefits go on indefinitely and can be enjoyed by the people of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia for decades to come.

The game can be changed

Decades of pursuing economic prosperity on the backs of extractive industries and fossil fuels have come to naught. Even when those industries grow and invest, the benefits do not filter down to local economies. That’s apparent in the conditions of cities like Weirton, Steubenville, and Wheeling that continue to suffer from depopulation and job loss even as fracking pads and pipelines invade the landscape all around them. That’s why the region’s leaders and policymakers need to explore new economic horizons with industries whose destructive impacts on climate and the environment practically insure that going forward any growth or opportunities they offer will be truncated as communities and nations seek healthier, more sustainable ways of living.

The game is changeable.

[1] State of My State blog post

[2] Dept of Numbers

[3] Considine study

[4] https://www.pennlive.com/news/2016/01/how_many_jobs_has_marcellus_sh.html