After the 2022 flood in southeast Kentucky, the Ohio River Valley Institute worked with the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center to do an initial estimate of the cost to rebuild housing damaged by the flood and found that the cost far exceeded the funds that had been secured for rebuilding at the time.

Since we published that analysis last February, more funding has been secured. Rebuilding has also progressed but some signs suggest that rebuilding costs will be more than we initially assumed. Based on an updated analysis, we find that a considerable gap—on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars—remains between the estimated $1.4 billion it will cost to rebuild homes in safer locations and the approximately $800 million in current or anticipated funds.

How much will it cost to rebuild?

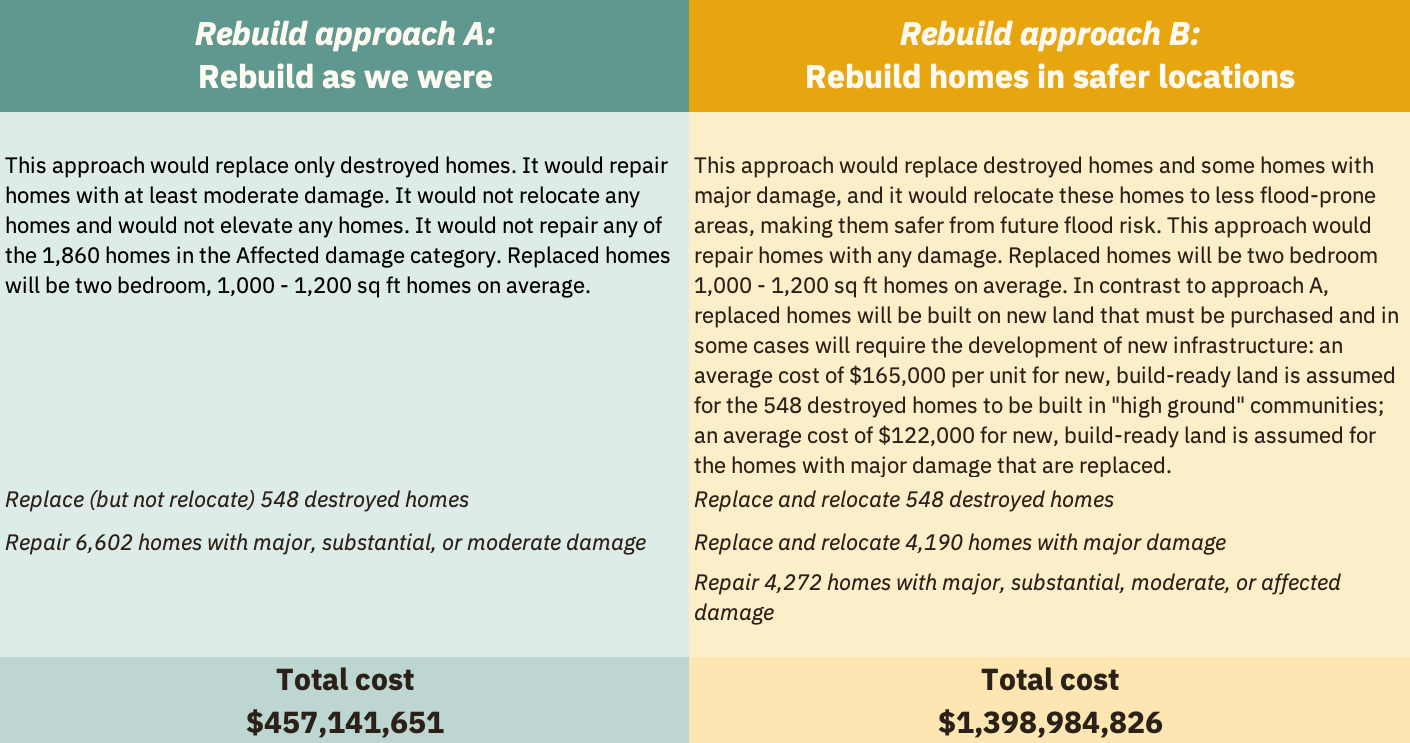

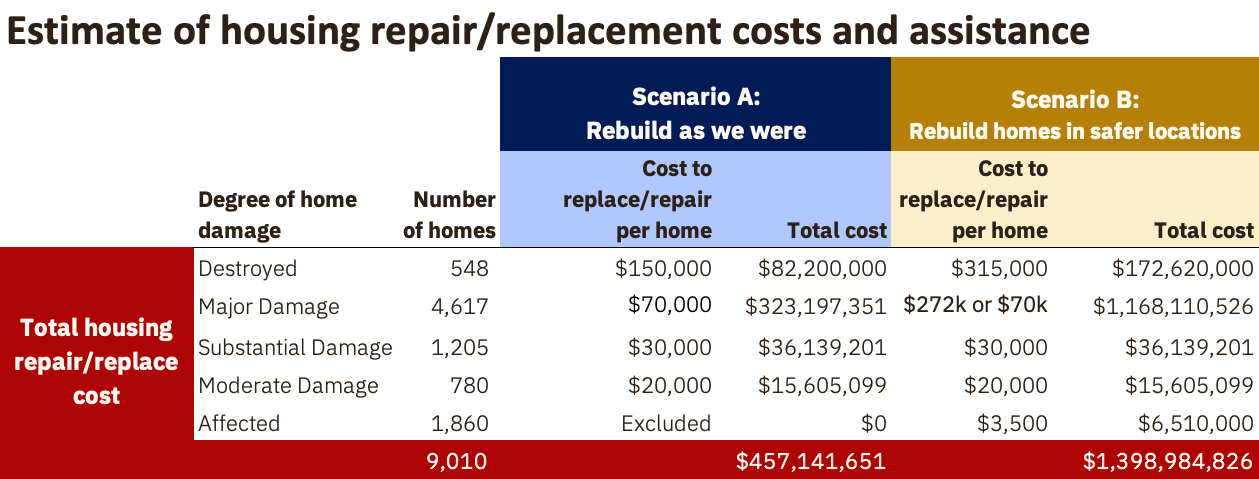

The cost of rebuilding depends on the approach to rebuilding, and especially whether you repair damaged homes or replace them with new homes in different locations that have a lower risk of future flooding. Immediately after the flood, we estimated that it would cost about $450 million to take the most bare-bones approach to rebuilding housing stock damaged by the flood (shown as approach A in figures below). This approach would’ve repaired most (but not all) damaged homes, and it would not build new homes for anyone except for the most badly damaged homes—and those homes would be rebuilt in the same flood-prone locations.

Thankfully, rebuilding has not gone the route of this bare-bones, rebuild-as-we-were approach. State and federal officials recognized the danger that would come with rebuilding damaged homes in locations that are likely to flood again and have taken a more ambitious approach. The clearest example is the seven “high ground” housing developments that the Beshear Administration is spearheading, which will build 665 new homes on former mine sites high above the area’s creeks and rivers.

Broadly, the approach to rebuilding housing damaged by the flood has been one that seeks to build new homes in safer locations nearby and gives families the option to relocate. Our updated analysis shows that if most of the homes that suffered major damage—based on inspections performed by FEMA after the flood—were replaced by new homes in safer locations, it would cost about $1.4 billion to rebuild all of the flood-damaged housing (shown as approach B in figures below).

Note: The number of homes and extent of damage is based on home inspections conducted by FEMA. See previous report or endnotes for more detail. Under scenario B, major damage homes will be either replaced in new locations (assumed average cost of $272,000) or repaired in placed (assumed average cost of $70,000).

As the “high ground” developments have been initiated, we’ve learned that the cost of acquiring sites for new homes will be higher than initially assumed because many of the housing developments will need infrastructure to be laid before home construction can begin. This means we’ll need to finance not just home construction but a significant amount of infrastructure for new housing, so the total cost will be higher.

In the counties hardest hit by the flood, housing development has been nearly non-existent for decades. There aren’t as many big, flat parcels suitable for easy development and, because the region is rural, the places where you can build often don’t have utility service. These are problems that the proper resources could overcome, but economic struggles have long persisted in the area.

The “high ground” communities will require water, sewer, power, and broadband to be laid. Many sites are at relatively higher elevations, so road and bridge development will be needed to access them. This will all be costly, but any new multi-home developments will be impossible without it.

The state is budgeting $146 million to build 462 homes—or $316,000 per home, on average—at the three largest “high ground” communities, according to documents filed with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In addition, many homes have and will be built in single lots that already have infrastructure. In these cases, non-profit housing developers are finding that the cost is lower because infrastructure doesn’t have to be laid. In our analysis we’ve assumed two-thirds of new homes will be in “high ground”-type developments and one-third will be on more traditional single lots. [Other assumptions can be found in the figures and endnotes; otherwise, the methodology mirrors that used in our prior analysis here using updated January 2024 data from FEMA.]

Many families that lost their homes to the flood have acquired assistance for housing repairs from FEMA or other sources and have pursued housing options that are inadequate, unsafe, or prone to future flood damage—but were the only option they could afford. For example, some families who lost homes have bought a travel trailer or even a storage shed and placed it back on their family land by the creek. Others have used their little FEMA aid to repair their homes, but often without elevating them even though they are located in areas that will likely flood again.

While some officials might count these families as having secured permanent housing, these should be considered temporary solutions and additional efforts should be made to secure safer, more adequate housing options for these families. We have not incorporated these cases into the cost estimate, which means the eventual total cost could be higher.

How much money has been secured to rebuild housing damaged by the flood?

So far, about $800 million in current or anticipated funds have been identified: $713 million in state, federal, and philanthropic funds have been dedicated to housing recovery from the flood, plus an estimated $85 million that homebuyers are anticipated to contribute to the purchase of homes built with these funds that will then be re-invested in more home rebuilding.

Most of the funds are provided to either homeowners whose homes were damaged in the flood or home developers who are building and repairing homes. About $320 million, or 40% of the approximately $800 million total, is in the form of grants or donations to housing developers to build new homes and do home repairs and provide those products at subsidized rates to homeowners.

The funds provided to homeowners are in the form of grants, loans, insurance payments, and buyouts: $102 million (13%) is in the form of grants to homeowners, $53 million (7%) is in the form of loans that will have to be repaid to the Small Business Administration, $24.6 million (3%) is in the form of insurance payments made to the few homeowners that had flood insurance, and a massive $214 million (27%) of these funds are in the form of property acquisitions wherein the state has purchased (or anticipates purchasing) flood-damaged property from homeowners impacted by the flood at pre-flood fair market value.

The three biggest government programs that are providing funds are: a federal Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) grant from HUD (of which $276 million goes toward housing), a buyout program run by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) ($135 million in buyouts for about 475 homeowners), and housing repair aid from FEMA ($88 million).

Across all these sources, the federal government is providing 91% of the funds to rebuild housing damaged by the flood, via mandatory programs and discretionary appropriations across five agencies. Philanthropy is providing 6%–mostly from local and state groups the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky and the Team East Kentucky Flood Relief Fund– while the state of Kentucky is providing only 3%.

Conclusion

The housing recovery so far has exceeded expectations in many ways. It has been miles from perfect—hampered by federal and state disaster policy that is too slow and too reliant on NGOs that have nowhere near the resources needed to rebuild and, in some cases, don’t prioritize rebuilding safer homes outside of flood-prone areas. But one of the biggest concerns after the waters receded was that there would be no real effort to relocate homes. That has not been the case: most of the non-profit housing developers as well as the Beshear Administration have gotten both serious and creative about finding a way to rebuild in safer locations.

About $800 million has been dedicated to or is anticipated for housing after the flood. That will probably build about 1,150 homes in new locations and provide over 800 buyouts, which homeowners could use to help build a new home nearby. But at the current level of funding, the rest of the damaged homes will probably be repaired in place. And that’s a big problem.

Why? According to home inspections by FEMA, 4,738 homes had at least one foot of water on the first floor (or at least one inch of water on the first floor of manufactured homes, which suffer more damage from less water). So at least 4,700 homes didn’t just have waves lapping at the front porch but took on serious water inside the home and could be at great risk as extreme precipitation and flood risk increase in the region.

The $800 million in identified funds will probably leave about 3,000 of these homes that took on serious water in harm’s way of the next flood. On the other hand, securing more funding above the current level—even if not the entire $600 million gap needed to fill the $1.4 billion in total estimated need—will help more and more families access adequate housing in locations that won’t put them at high risk of taking on water again in the coming years.

Endnotes

- We assume homes in the Major Damage category are either replaced with new homes at an average cost per home of $272,000 (inclusive of new infrastructure and land costs) or repaired in place at an average cost per home of $70,000. We assume half of stationary homes in the Major Damage category that experienced 2 to 13 inches of water on the first floor in the flood are repaired in place. All other homes that suffered Major Damage are replaced in new locations: we’ve assumed two-thirds of new homes will be in “high ground”-type developments and one-third will be on more traditional single lots – yielding an average cost per new home of $272,000. It’s possible that the cost per home for “high-ground”-type homes could decrease if a significant share of additional homes are built adjacent to this first phase of developments and thus don’t need extensive infrastructure development– but no such plans have been set and even in that case some additional “high ground” sites would still need to be developed. Further, the first round of “high ground” sites were presumably the most ideal; additional “high ground” sites may be further from town or existing infrastructure, which could increase costs. Nonetheless, if the average cost to replace majorly damaged homes was reduced – to $225,000, for example –the total cost to rebuild housing from the flood would still be $1.203 billion.

- Kentucky Housing Corporation (KHC) also had a budget of $108 million statewide in its "Housing Credit - Equity from Private Sector" program for 2023 and 2024. Flood-impacted homes were eligible, but it is unclear how much, if any, of this credit went to these programs. Similarly, HOME funds statewide for single and multifamily homeownership production, managed by the Kentucky Housing Corporation, totaled $25.9 million for 2023 and 2024. Housing projects in flood-impacted areas were eligible, though it is unclear how much, if any, of these funds went to flood recovery housing. For this reason, these programs have been excluded from our calculation. KHC also offered a Low Income Housing Tax Credit carveout for the area, but there weren’t any applicants in 2023. It is unclear to what extent CDBG-MIT funds have been secured for housing-related efforts after the flood.

- “Anticipated homebuyer contributions to be reinvested” assume that homebuyers purchasing homes financed by funds provided to housing developers will contribute, on average, $60,000 per home purchase, which will then be reinvested in financing more new homes. Analysis of a sample of 19 homes built by Housing Development Alliance since the flood found that homebuyers contributed, on average, $5,000 in personal savings and $55,000 in amortized loans. The average annual income of homebuyers in the sample was $32,000, which is similar to the average income of homebuyers we might expect to purchase new homes financed by these programs. Data from the Census Bureau shows that the median household income in the four hardest hit counties varied (by county) from $38,209 to $45,330 in 2022, but data from applicants for FEMA aid in 2022 after the flood suggest that the median household income of those whose homes were flood-damaged was lower than the area median and could be below $30,000 annually. Assistance that homebuyers might have received from other government programs, such as FEMA aid or buyouts, have been excluded from our calculation, given that the specific terms of the financing for new homes under these programs are not yet known.