There was a time when the sight of rows of office workers hammering away at their Friden adding machines would have sent me into paroxysms of delight because I, the Victor Comptometer salesman, had a new and better “programmable calculator” that could kick the Friden’s ass.

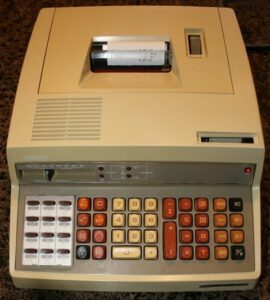

The Victor V4900 programmable calculator circa 1978

I was a young 1970s college graduate entering the workforce at the tail end of the era of mechanical business automation. Typewriters, adding machines, and mechanical cash registers were still the workhorses of stores and offices.

Behind all that machinery were companies – Burroughs, Monroe, Friden, Victor – whose names were as familiar then as Cisco, Oracle, and SAP are today. And those companies supported factories, sales offices, and repair facilities that provided living wage jobs to hundreds of thousands of workers and their families.

Then, within a little more than a decade, it was all gone. A year after I fizzled as a Victor salesman, I was playing at home with my new Radio Shack TRS-80 home computer and five years later, instead of an adding machine and typewriter on my desk at work, there sat an Apple II desktop computer, precursor to the Mac.

Gone too were those hundreds of thousands of jobs plunging not only workers and families, but entire communities, into financial crisis. One could argue that Dayton, Ohio, once home to National Cash Register and the business forms giant, Standard Register, never recovered.

The knock-out blow suffered by the office automation industry was as ferocious and sudden as the one that hit the American steel industry a few years earlier, the textile industry a few decades before that, and also as the one that possibly faces workers in the fossil fuel economy today.

So how did we as a society help displaced workers and communities manage the economic consequences of the transition from the mechanical workplace to a digital one? We didn’t. Thanks to the New Deal, we had unemployment insurance and Medicare and Medicaid were brand spanking new. But that was about it – a little help for individuals and families and none whatsoever for communities.

As a minor refugee of that great purge (after Victor, my next job was with the aforementioned Standard Register), and having grown up in a town that was economically devastated by the collapse of the steel industry, I have a special appreciation for the focus now being given to the need for economic transition assistance for people and communities whose livelihoods the clean energy transition threatens to sweep from beneath them.

But I find myself wondering why this new concern, this new consciousness has arisen. Are we more aware of the pain caused by economic displacement and deprivation than we were in the 1970s and 80s? Are we more caring, more socially conscious than we were then? Hard to believe since we had just come through the 60s, when the concept of social justice was practically invented. And it was still a time when anyone over the age of 50, which is to say almost all policymakers, had personally lived through the unimaginable misery inflicted by the Great Depression.

Still, I think it’s incontestable that, at least at a policy level, we are more caring. But something else is going on as well and it suggests that the frequency with which we hear expressions of concern for workers and communities isn’t just the product of heightened compassion. That “something else” may also account for why, despite the expressions of concern that come from all points on the political compass, so little agreement has arisen about what can or should be done to create jobs and help workers and communities that may be vulnerable to economic disruption.

To put it bluntly, much of the concern we hear expressed for workers, jobs, and communities is disingenuous. In present-day America, “jobs” is the principal currency of public discourse. Folks on the political left may care and talk a lot about equity while folks on the political right care and talk a lot about American values, but the thing both sides talk about is jobs — how to create more of them and the risks of losing them.

But how much do we really care? One measure is the degree to which we’ve developed and implemented actual strategies to deal with the coming energy economy transition that is at least as inevitable as the transition from the mechanical to the digital workplace. And the sad reality is that we really haven’t.

In a way, that’s not surprising. We’ve long grown accustomed to empty rhetoric from fossil fuel industry leaders who justify their pleas for tax breaks and regulatory relief by crying, “We must preserve jobs!”. Then they use their savings to line their pockets, while gleefully investing in new and often environmentally destructive technologies that eliminate rather than create jobs.

But, if the ostensible concern for jobs expressed by corporations and policymakers is driven mostly by political expediency, expressions about the need for equitable transition by some people on the left is similarly disingenuous.

Confronted with policymakers who are fearful that embrace of clean energy transition will result in a politically disastrous loss of high-paying jobs in coal mining, natural gas, and fossil fuel power generation, environmental advocates tout the job creation potential of clean energy industries and suggest without explaining how or why that new clean energy manufacturing facilities will locate in highly impacted communities.

These suggestions are maddeningly vague. And some of the advocates privately resent the fact that they’re required to conjure up special solutions for a numerically tiny subset of fossil fuel workers who’ve enjoyed the highest paying of blue collar jobs for decades while throughout the economy many other workers have done far less well, are equally at risk, and yet no one is proposing special assistance programs for them.

In short, regardless of whether someone supports or opposes clean energy transition and regardless of whether they do so from the left or right, if their attitudes toward jobs and equity are driven more by political considerations than they are by compassion or even simple economics, their policy responses will follow accordingly.

On the right, that might mean supporting federal spending on technologies such as carbon capture and sequestration for fossil fuel power generation in the hope of protecting existing fossil fuel industries and hypothetically jobs as well . . . but at a cost.

Had a similar approach been adopted in the 1970s and 80s, when adding machines and typewriters were threatened by desk-top computers, we probably would have proposed subsidies for terminal branches on the technological evolutionary tree, such as programmable calculators and word processors, in a foolish and inevitably futile attempt to stave off the onslaught of the personal computer.

On the left, economic transition policies driven by political considerations might lead to disbursements of funds to organizations, businesses, and communities that represent key constituencies, but whose use of the money would have only fleeting benefits and do little to stimulate sustained job growth, improved quality of life, and long term economic development.

It’s wonderful that today we’re more focused than we were in the 70s and 80s on jobs, the potential pain of unaddressed economic upheaval, and the need for transition strategies. It means that, for the first time in my life, we have an opportunity to revive parts of the rust belt, Appalachia, tribal communities, communities of color, and other parts of the country that have struggled economically for decades.

But we must also recognize that for some people, including many policymakers, their focus on jobs and equitable transition extends only as far as their political lenses allow them to see. And from that truncated perspective can emerge policies that squander precious funds and are doomed to failure while alternative strategies that are proving effective in generating both jobs and economic growth, such as the coal transition plan in Centralia, Washington about which I wrote recently, are overlooked.

In summary, it’s good that we now talk about jobs and equitable transition, but we need to get serious about what that means — the strategies, the resources, and the outcomes — and how we’re going to bring them about.