On Friday, US Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) released a new version of his proposed energy infrastructure package. The previous version of his proposal included $11.3 billion in federal funds to clean up damage from Abandoned Mine Lands (AMLs) across the country. The new bill adds some important provisions, but alarmingly has dropped policies key to ensuring AML funds are spent remediating damage in places that need it most.

The new provisions could help raise wages of reclamation workers and unionize the AML sector, and are important additions. However, it’s unclear if the package will drive up wages to living wage levels without additional labor provisions, such as explicitly applying the minimum hourly wage requirement of $15 for federal contractors and requiring Project Labor Agreements (PLAs) for AML contracts. Perhaps most important: leaders in Congress should create a new public reclamation jobs program under the Civilian Climate Corps (CCC) and link it with mine cleanup.

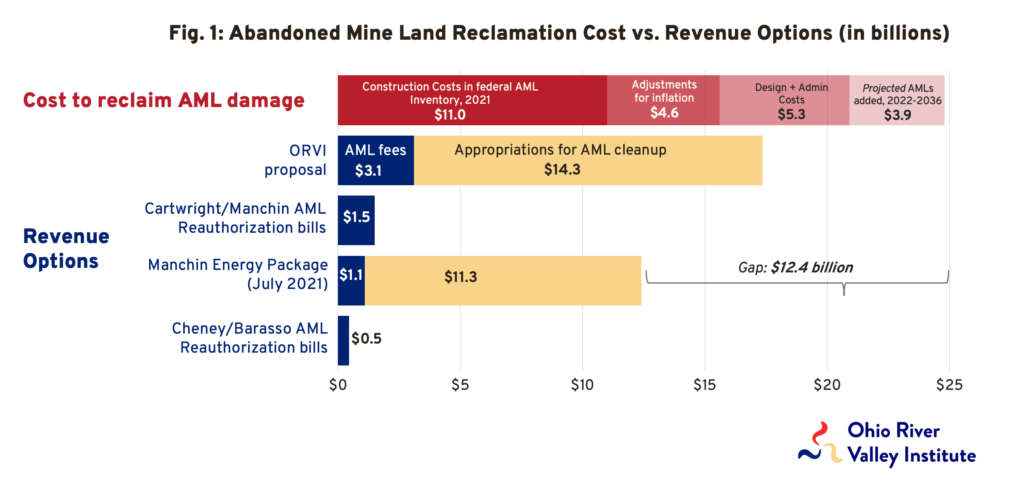

This new proposal, critically, adds a 13-year extension of the AML fees that finance cleanup. But the proposal would lower those fees by 20%, costing about $460 million relative to maintaining the current fee levels in Manchin’s standalone AML reauthorization bill. (See figure 1, which is discussed in detail below). It’s important that Congress hold the coal industry responsible and raise the historically low AML fee levels—not lower them further and garner even less revenue to clean up the backlog of AML damage.

Perhaps most concerning is that under the new bill, AML funds would no longer be distributed to states and Tribes according to the extent of remaining damage, as was proposed in the previous version. It’s great that the bill does seek to ensure funds are used strictly for AML reclamation, but that goal is in tension with a funding formula that would send AML dollars to states that don’t need it. Congress should reinstate the provisions from the previous bill that would update the government’s inventory of AML damage and distribute AML funds accordingly, as well as incorporate language from a recent bill that would ensure states can’t spend funds on non-AML cleanup.

A win for workers, and a 13-year lifeline for the AML program

First, the good news. The new bill maintains a proposed $11.3 billion over 15 years in appropriations for AML cleanup. That’s a categorical step up from current funding levels, and a huge win for residents and workers living in the shadow of mine-scarred hillsides and downstream of AML-polluted water. Plus, this new bill adds a 13-year extension of the fees levied on the coal industry that help finance AML cleanup, which are set to expire this September. Including this in the infrastructure package will provide long-term stability for the program and communities who depend on it.

There’s also an exciting new provision to help unionize the AML sector. It would encourage state agencies to group cleanup projects in the same geographic area together in a single contract, making contracts larger and more feasible for union contractors. The United Mine Workers of America and the Kentucky AFL-CIO have called for the idea, and ORVI proposed the provision in our report released in April. The new bill also maintains the requirement in the last version of the bill that AML contractors will have to pay workers prevailing wages (i.e. Davis-Bacon wages), which is not currently required for AML cleanup. These are key steps forward that should help build power among reclamation workers and put more money in their pockets.

Now onto the bad news. Manchin’s original proposal made some much-needed changes to how cleanup dollars will be split between states and Tribes, but those changes aren’t in this new bill. There are two basic aspects to this: where the money flows and what it’s spent on.

Where will the money flow?

The bill contains a formula that will be used to split reclamation money up between the 28 states and Tribes with AML problems. You would expect that a program seeking to address environmental damage would divvy up money based on which states have more or less damage to clean up. The trick is that we don’t have data on the extent of that damage that is reliable enough and consistent across states/Tribes to base funding on it. Lacking a good yardstick for how much damage (or need) a state/Tribe has, the government currently uses a complicated formula based on how much coal a state/Tribe produced before 1977 and in the last year. The idea is that how much coal was extracted in a place is a proxy for environmental wreckage.

Manchin’s previous proposal fixed this formula by updating the inventory of AML damage (i.e. creating a reliable and consistent yardstick of a state/Tribe’s need) and then used the distribution of damage as the basis for the formula. If a state/Tribe has 15% of damage nationally, for example, it would receive 15% of clean up funds for this year. The inventory would be updated as cleanup occurs, so next year’s formula might shift as reclamation progresses and the inventory is updated.

The new bill leaves out these fixes, instead using a state’s coal production before 1977 as the basis for the funding formula. Call me old-fashioned, but if we’re going to spend $11.3 billion in public money, creating a reliable database of where the problems are and sending the money to those places seems like an important first step. Maybe historic coal production is a fair proxy for AML damage. Maybe it’s terribly off. There’s no way to know until we have a reliable account of damage across states and Tribes to compare it to. Hence, the need to update the inventory and base the distribution of funds on that.

All this money will be spent on mine cleanup, right?

The second area of concern with the new proposal has to do with what projects qualify for AML dollars, and to understand it we need to talk some about the context of the existing AML program. Legally, states or Tribes that contain AML damage are classified as: 1) those with outstanding AML damage (i.e. “non-certified”), or 2) those that have “certified” that they’ve cleaned up all their AML damage (confusingly, certified states/Tribes often still do have outstanding AML damage in their borders, but this legal designation provides policy perks I’ll get to).

There are different funding streams for non-certified and certified states/Tribes, and the funding streams have different limits on what the money can be spent on. Most states are in the former camp (“non-certified”), and for them the law requires AML funds be spent restoring damage from the pre-1977 coal industry—as it should (the “AML Pilot Program,” a separate funding stream from standard AML cleanup, is a notable exception to this that has drifted beyond AML cleanup in some states). Certified states/Tribes continue to receive AML appropriations after they’ve “certified” and for them the law is squishy, ultimately allowing the legislative authority in the state/Tribe to spend AML dollars on non-AML items.

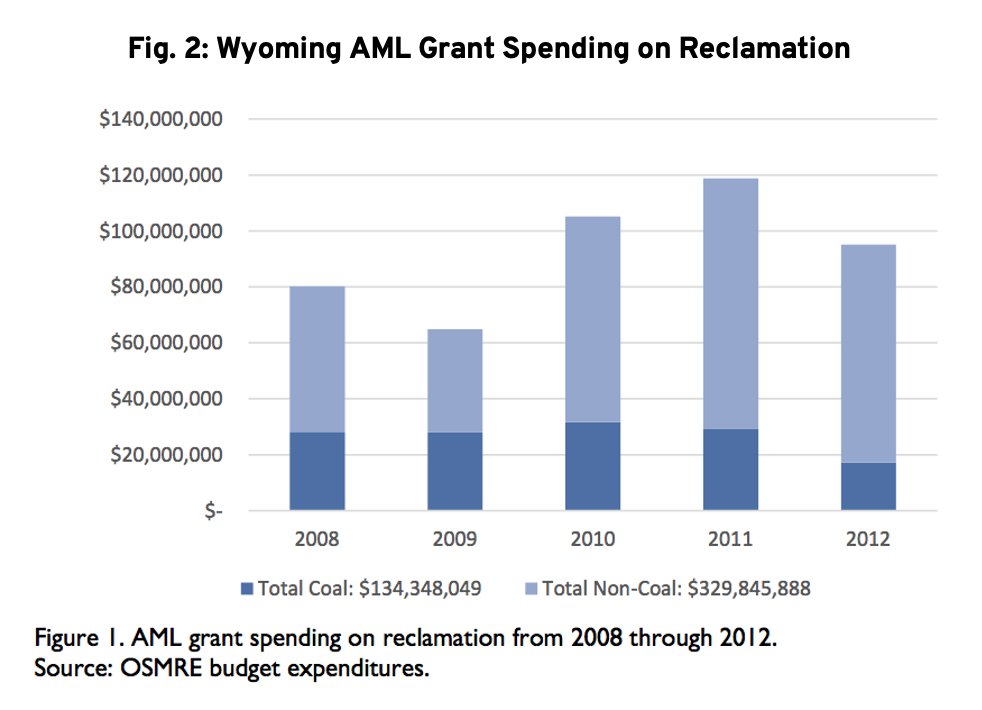

Certified states/Tribes are a minority of the states/Tribes with AML damage, and Wyoming has received the vast majority of certified funds in recent years. In 2017, the Inspector General in the Department of Interior released a report concluding that certified states/Tribes had not prioritized coal AML cleanup with their AML funds. The report found that only 29% of Wyoming’s AML funds from 2008-2012 were spent on coal AML cleanup. For example, the 2017 OIG report found that “Towns like Rock Springs, WY, currently face significant subsidence issues due to historical coal mining. Reclaiming these sites will likely cost nearly $100 million; however, Wyoming is diverting AML grant funds to other projects instead of giving coal reclamation projects top priority.” Figure 2, courtesy of the OIG report, shows the figures for 2012-16.

In 2012, Rep. Paul Ryan proposed a budget that would eliminate AML grants to certified states/Tribes because “for the states that have been ‘certified’ as having successfully restored critical mining sites, the mine payments serve as an unrestricted Federal subsidy.” Though Ryan wasn’t successful in eliminating the grants, another bill in 2012 did limit certified funds to only $15 million annually—which only impacted Wyoming. By 2016, the Wyoming delegation had succeeded in eliminating the cap, and, incredibly, scored Wyoming a retroactive payment of $242 million dollars in certified AML funds for the years that the state’s payments had been capped. That’s a lot of unrestricted cash. For context: the total AML payments to all 20 non-certified states in 2016 was $163 million.

The thing is Wyoming does have outstanding AML damage from pre-1977 coal mining, and federal AML funding should finance the cleanup of those problems. But the current policy regime sends a more-or-less blank check to certified states. The money has been used for hardrock (non-coal) reclamation, roads, water and sewage infrastructure, and other projects. It’s not that all of these projects are bad, it’s that the need for projects like these exist in other states too— yet only certified states/Tribes have the luxury of loosely spending AML funds on them. More to the point: if these leaky spending provisions aren’t plugged, it could be decades before the country cleans up the tens of billions of dollars worth of coal AML problems that persist.

In the past, Wyoming legislators have argued that the significant chunk of national AML fees collected from coal companies in their state is “money from Wyoming for Wyoming.” But the $11.3 billion for AML cleanup proposed in this bill isn’t financed by AML fees. Manchin’s new proposal appears to limit the use of AML funds to cleanup and water restoration projects. That this bill seeks to spend AML funds strictly on reclamation is a big step forward, but it’s in stark tension with other provisions in the bill that would continue to send funds to states that have certified.

What happens when states clean up all their AML damage but keep getting piles of cash? There’s a provision that’s intended to redistribute unused funds in later years, but it could be as late as 2041 under the current language. And it could create a situation where states try to find a way to spend the money earmarked for them on other projects, especially given the policy context of a long history of AML funds being used by certified states for non-AML cleanup.

A cleaner way to address this has been proposed in a bill re-introduced recently by Senator Booker and Representative McEachin: explicitly disallow certified states from using funds authorized under this package on non-coal AML cleanup (Manchin’s proposal says how funds can be used but doesn’t explicitly state that they can’t be spent like other certified funds in SMCRA), and base the funding formula on coal AML damage as covered above. States would receive funding based on their level of need, ensuring that certified states receive the funds they require to clean up AML damage – but only to the extent that they need it for AML and without a free hand to prioritize other projects.

This isn’t just about Wyoming: with $11.3 billion worth of funding, it’s possible that some of the 20 states that are currently non-certified will seek certification status in a few years and will continue to receive funds based on the current formula. Why send money to certified states, tell them they can’t use it, and then wait years to redistribute it when we could send the money to the states that need it in the first place?

What about Tribes?

The Booker-McEachin language rightly maintains flexibility for certified Tribes, whose relationship to the federal government is categorically different—both legally and historically—from certified states. Tribes were initially not allowed to operate their own AML programs because the federal government deemed them incapable under SMCRA. It took a dozen years after the creation of the AML program for the Navajo Nation and the Crow and Hopi Tribes to finally gain approval to operate their own AML programs in 1988-89. For reference, this was 5 years after Wyoming achieved not just its approval for a program but its certified AML status in 1984.

In the early years, OSMRE reserved Tribal AML funds in an account, waiting for the Tribes to gain approved AML programs. A 1986 GAO report shows that OSMRE proposed diverting these Tribal AML funds into an OSMRE discretionary account because the money was lingering. It’s unclear from the GAO report whether these funds were delayed, used by OSMRE for AML Tribal cleanup, or ultimately diverted from Tribal cleanup. In any case, Tribes were denied autonomy over their programs for more than a decade, likely setting back cleanup and impacting AML spending choices on Tribal lands. These setbacks, driven by OSMRE’s initial denial of Tribal AML programs, merit continued flexibility over the AML funds that Tribes would see through this package.

The new bill would lower AML fees by 20%, costing $460 million in revenue

The last bit of bad news is this: the new package weakens accountability of the coal industry by lowering AML fee levels by 20% and by shortening the fee collection from 15 to 13 years. Manchin has a standalone bill that maintains the current fee levels for 15 years. The Wyoming delegation has a bill that lowers fee levels by 40% and continues collection for 7 years. Figure 1 compares these three proposals with the doubling of fee levels proposed in ORVI’s recent report (AML fee projections are based on coal production projected in the EIA2021 Reference Case scenario). The figure also compares these revenue options with ORVI’s estimates of the cost to reclaim all outstanding AML damage (it includes the cost of AML problems projected to be discovered between now and 2036, or 15 years from now; and construction cost estimates are a conservative approximation that seek to take into account 2021 AML cleanup that the inventory does not yet reflect).

Wide-scale mine cleanup could have a huge impact for communities struggling with lingering pollution and workers unable to find good-paying work. But the policy details need to be right—especially for an investment this large. Congress needs to do more to ensure reclamation jobs pay living wages and are accessible, to raise more AML revenue for the long list of cleanup needs—not lower AML fees— and to make sure that reclamation dollars go to the places that need them most.