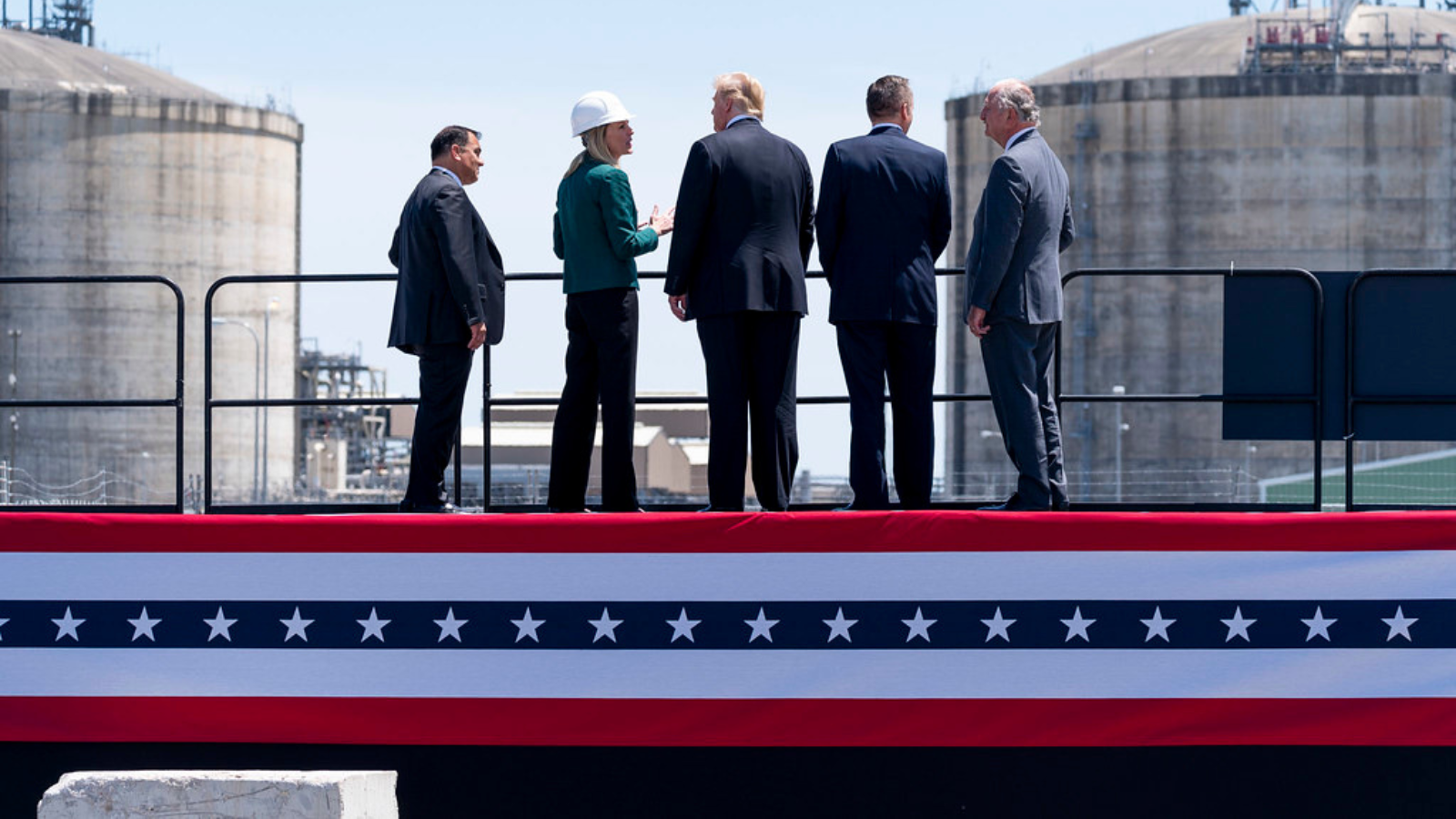

Joanne Kilgour: Today’s discussion comes on the heels of an executive order signed by President Trump reversing the Biden administration’s pause on pending and future applications for LNG export projects. We’ve gathered a panel of experts today to help us unpack what this new political landscape might mean for consumers and local economies across Appalachia…So again, thank you for joining us today. And now please join me in welcoming our distinguished panel:

- Eric de Place, Principal of Salish Strategies and Senior Research Fellow with the Ohio River Valley Institute.

- Alan Zibel, Research Director at Public Citizen.

- Elizabeth Marks, Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Utility Law Project.

- Sean O’Leary, a senior researcher here at the Ohio River Valley Institute.

Part I: LNG 101 and the flow of gas from Appalachia to the Gulf

Key findings:

- Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is mostly methane extracted via fracking, super-cooled to 1/600th of its volume for easier storage and transport, then shipped globally for power generation, heating, and other applications.

- Pipelines ship significant amounts of Appalachian fracked gas to LNG export terminals along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Texas. Major producers like EQT have contracts to ship Appalachian gas southward via the Transco pipeline— the largest interstate gas transmission system—and a suite of new pipeline expansion projects that would further link Appalachian gas to export markets.

- Closer to home, momentum is building to complete LNG export terminal projects in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland in order to ship gas directly from Pennsylvania onto Atlantic markets.

Joanne Kilgour: Eric, could you give us a quick background on LNG exports and the relationship between LNG and the flow of gas from Appalachia?

Eric de Place: Absolutely. We’ll start at a sort of a 101-level and then we’ll move up from there pretty quickly.

Just so everyone is on the same page about this industry, LNG, or liquefied natural gas—which sounds like an oxymoron. How could a gas be liquefied?—is mostly methane gas. It’s extracted by fracking. Once it is extracted and processed, it’s then moved in a pipeline to a facility, usually on the Gulf Coast, where it is super-cooled and compressed and it shrinks in volume dramatically to about 1/600th of its size.

That makes it much easier to store and transport. In that liquefied state, the natural gas is then loaded onto specially designed ships and moved into world commodity markets where it’s used for a whole range of purposes, including power generation, building, heating, and some other stuff.

So liquefied natural gas is fundamentally, of course, connected to the big frack fields in Appalachia and in other places. That’s the underlying dynamic. And now we’ll talk a little bit about how this stuff moves from place to place and why it affects Appalachia.

The Ohio Valley Institute, of course, is principally focused on the Appalachian region of Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky. And that is actually not where most of the LNG export proposals are located. This is just one map. There are actually several different versions of this kind of map showing the distribution of existing LNG export facilities as well as those that are under construction and planned. The vast majority of those are in Louisiana and Texas. There are a couple of small ones on the East Coast, pretty far from Appalachia.

And so it has been the thought historically, although this is not really accurate, that most of the gas supplying these exports would come from Texas or Louisiana—there’s some large shale gas plays in those areas. And it’s true, those shale plays will feed much of the export demand for this product. But this actual story ends up being more complicated than that.

This is a graph from the US Energy Information Administration showing how much LNG export capacity the country has right now. In 2016, we had very, very little. Nowadays in 2025, we’ve got a lot. We are the world’s leading producer—that is, fracker—of natural gas and also the world’s world leading exporter of liquefied natural gas.

On top of what we’ve done now over this last 10 year period, there’s been an absolute boom in production and export of gas. There are proposals, active proposals to roughly double that amount of export, which is going to move a ton of US gas into world markets.

The way this works is a lot of that gas, like I mentioned before, will be produced in Texas, will be produced in Louisiana. But we have increasingly been able to document that some of the gas will actually be extracted much farther north. EQT, which is a leading US gas producer—certainly in the top three, maybe one of the biggest, maybe the biggest gas producers almost entirely based in Appalachia—we have identified specific contracts that EQT has to deliver gas to Louisiana and Brownsville, Texas, all the way at the southern tip of Texas. Which means that at least that portion of gas will be traveling a long distance in order to feed that stuff. So there’s a direct connection now between Appalachian production and what’s happening or proposed to happen on the coast.

In fact, it’s a very large percentage of EQT’s production. And these are just the contracts we know about. There are likely other contracts that we don’t know about. So it means that If you’re concerned about LNG exports in the Gulf, you need to be thinking about fracking in Appalachia and vice versa.

This is a very, very simplified schematic of the physical flows of gas. This actually reduces a lot of the detail and complexity in the system, but it is designed to illustrate what is the fundamentally important underlying dynamic here. So in the Appalachian Basin, that’s kind of that grayish blob there that you see sprawled over Pennsylvania and surrounding states, that’s the Marcellus and Utica gas fields. Not all of that is being actively extracted, but much of it is. If it were its own country, it would be the third largest gas producer in the entire world, just that blob right there. That’s how prolific it is.

From that region, the gas flows out into a variety of places, many of which are actually not shown on this map. But the main one for our purposes is that green line that runs from New York down to Texas. That’s the Transco pipeline. It’s the biggest interstate pipeline transmission system in the United States and it feeds gas all over the eastern seaboard and along the Gulf.

And Appalachia’s gas, a lot of it’s flowing into Transco. The Mountain Valley Pipeline, which many people have heard about, was a hotly contested pipeline expansion going south through West Virginia, also feeds into Transco. And because of all this new gas that’s flooding into Transco, there’s been this kind of popcorn of smaller expansion projects to enlarge the capacity of Transco and of ancillary pipeline infrastructure connected to it to allow more gas to reach more markets.

All this stuff, it was designed for multiple purposes, but one of them is to advance LNG exports.

One of the complicated ways in which this happens is, we talked earlier about how EQT has direct contracts with LNG export facilities on the Gulf. In addition to the direct contracts, there’s also this backfilling phenomenon. So as gas that formerly would have been supplied from, let’s say, Louisiana or Texas into the Southeast into the large population centers there, as that gas gets redirected to LNG exports for foreign markets, then Appalachian gas replaces that gas. In the Southeast, particularly. And so NDQ and other pipeline or other gas producers have actually said this to investors that they expect that with the proliferation of LNG export facilities, they will have more market share into the Southeast, especially also the Midwest, supplying that gas, again, to sort of backfill what’s moving then out of the country.

And this one is brand new. This is kind of another one of the breadcrumbs that we’re putting together here. This is a brand new proposal that became public, I think, about a week and a half ago. And it’s a complicated Kinder Morgan proposal with a terrible map that they produced. You can see I put a red arrow there to a green line that’s kind of hard to see. But these are actually two pipeline systems in the southeast, both of which Kinder Morgan is proposing to expand by 1.2 billion cubic feet per day, which is a lot of gas.

And that little green line connects from the Transco system that we talked about, the big East Coast pipeline system, to a little place near Savannah, Georgia that has an existing LNG export facility now. It’s called Elba Island. And I think it is quite likely that we will see expansion proposals at Elba Island. Because essentially now this takes gas from the Marcellus into Transco, maybe via MVP, and now through this little green line, it’s going to get expanded right to Elba Island. So another way in which Appalachian gas is likely to move overseas. And in fact, in some of Kinder Morgan’s early documentation about this, they actually say that Pennsylvania and Ohio will be feeders into this expansion project in the southeast. And I think it’s no accident that that green line heads right to the coast.

And then the other possible way in which Appalachian gas production is connected to LNG exports would be what Energy Secretary Chris Wright was telling lawmakers during his nomination hearing. According to him, there should be LNG exports directly from the mid-Atlantic. And there have been two proposals in the past to develop LNG export terminals in the Philadelphia region, one in New Jersey, one on the PA side. Those haven’t gone anywhere so far, but there is probably increasing energy behind building out those proposals in order to ship gas directly from Pennsylvania onto Atlantic markets.

There is also a small existing facility in Maryland called Cove Point that at least in theory could be expanded and it would be, of course, much closer to the Appalachian gas fields than the stuff down south. So all this to say, this is kind of just a super quick flyover of what the physical infrastructure looks like and how the gas actually moves from Appalachia into the big LNG export proposals And it is, I think, very much the case that more than we have understood in the past, what’s happening in Pennsylvania is directly connected to the big debate we’ve had about LNG export expansion, which is mostly a Gulf phenomenon, but just a very clear linkage now between those two regions.

Lots of impacts of this stuff; lots of reasons to care about this. There are many associated risks with fracking which I won’t fully litigate here because I need to keep my time short. It’s going to raise prices for US households and consumers because it effectively puts American buyers in a bidding war with foreign buyers. Other panelists are going to talk a lot more about that than I will here.

And of course, there are the risks of climate change associated with extracting and burning a lot of fossil fuels like natural gas. With that, I’m going to stop. I realized that was a super quick approach to all this stuff. I’m happy to dig deeper in Q&A, but I wanted to leave lots of time for my fellow panelists to explain the stuff that I flew right by.

Part II: US LNG expansion and the current state of play

Key findings:

- Prior to 2016, the US LNG industry was practically nonexistent. Today, it’s booming, with eight export terminals currently operating and more in development.

- Expanding LNG exports could lead to a $9.6 to $15.7 billion increase in Pennsylvania gas expenditures, with households across the U.S. paying an average of $122 more annually for natural gas and electricity.

- Expanding LNG exports would also deliver a windfall for US fracking companies while pushing up prices for American consumers and harming the climate and vulnerable communities.

Joanne Kilgour: Eric, thank you so much for providing that really grounding overview. And now, Alan, I’d like to turn to you. You’ve recently published two reports examining LNG exports, including Keystone Gas Gouge, showing that gas export push could stick Pennsylvania consumers with a $16 billion bill, and Gassed Up, reviewing Trump’s aim to quickly approve 14 gas export terminals. Could you share with us the findings from these reports and what they can tell us about the current state of play with respect to LNG exports in Appalachia?

Alan Zibel: Yes, sure thing. And thanks for having me. This is great stuff and I love nerding out on LNG.

The first two slides are a little duplicative, but I kind of want to run through them anyway. The thing I’d emphasize is just how quickly this industry has boomed from essentially nothing in 2016 to huge exports now. And even this one, which I think is published in September, is out of date. The Plaquemines project opened in December, so now we have eight terminals open and operating with more to come.

And they’re not just in the US; they’re also in Canada and Mexico. Really interestingly and importantly, the proposed terminals in Mexico have to be approved by the US Department of Energy because they are exporting gas produced in the US rather than in Mexico.

The proposals are really on the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana, and you can see Cove Point and Elba island on there, too.

But the bulk of my analysis has been about the impact on consumers. Really interestingly, a little more than a year ago, the Biden administration at the time paused LNG export approvals. The only thing that was put on pause was the permission to export the commodity, so the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) was still evaluating new projects and making decisions, and there’s tons of gas being exported.

The industry tried to characterize this as a ban on LNG exports, but that was completely untrue. It was a pause on new and pending approvals of gas. Kind of annoying how the industry mischaracterized that.

After about a year of studying, the Biden administration—somewhat surprisingly, in a welcome development—agreed with us and with consumer advocates.

We would not have predicted that in January of 2024, but by the end of the year, they had analyzed the data and they came to a pretty stark warning. Former Secretary Granholm warned that unfettered LNG expansion, a “business as usual” approach, is neither advisable nor sustainable. She warned about a triple cost increase: the increasing price of natural gas; a resulting increase in electricity prices, because natural gas is used to produce so much electricity; and increased costs for consumers from the pass-through of higher costs to manufacturers.

The DOE study found that households across the country would pay, on average, more than $122 per year more for natural gas plus electricity. That’s on average. There are regional differences, and, of course, an average number is going to smooth out volatility and could very well understate real costs.

The study also found that for industrial businesses, overall energy costs would go up $125 billion, leading to an inflationary impact for a wide range of consumer goods.

The Energy Information Administration also said just two days ago that the wholesale price of natural gas in the US is expected to rise through next year and reach about $4.20 per million btu.

They also expect that [increasing gas prices] will result in a decline in the share of power generation from gas and more renewables—an interesting side effect.

Nationally, if you summed up the increase in natural gas costs across all sectors from 2035 to 2050, it would range from $165 billion to $271 billion.

I did this by looking at a well-known energy forecaster, Jesse Jenkins at Princeton, whose analysis of the eight plants held up by the Biden administration identified a “low-impact” scenario of a $0.33 increase in gas prices and a high-impact scenario of $0.54 cents if all eight projects went through and got constructed.

Our report, which Joanne mentioned at the top, calculated—using the same methodology—a $9.6 to $15.7 billion dollar increase in Pennsylvania gas prices, gas expenditures in that time period.

Where does Pennsylvania get its electricity? More than 60% comes from natural gas. So you can see how it kind of flows through electricity prices and it’s also going to flow to manufactured goods.

Another report that we did in January with our friends at Friends of the Earth works to create a database analyzing the supply agreements for all these LNG terminals to determine which of these are the most commercially viable.

Typically, a bank won’t just give these multi-billion dollar LNG terminal developers money for construction. It’s not financially viable; the bank won’t just hand out the money to build it. So the developers need to hit a certain threshold of contracts, signed agreements to buy the gas, before they’re going to get the money to build the thing.

The most commercially viable project we analyzed is called Mexico Pacific being built by a private equity firm out of Houston and a bunch of other investors. This one is on the Gulf of California in Baja. That Mexico play is really designed to send gas to China and not having to go pay the additional expense of going through the Panama Canal. So that gas would definitely not come from Appalachia. It would come from the Permian. So these are, you know, pretty interesting data in my mind, showing how some of these are on solid ground commercially, while some are not.

This contract data is fascinating because it lets us see who’s buying the gas. And you can see that the biggest buyer of these 14 projects that are pending approval from the Trump administration is Saudi Arabia, the state-owned gas company Aramco, followed by Shell, then Vessel Gasification, a company in India. It’s essentially big oil majors and then oil majors, oil training companies, trading desks, China, Malaysia.

A really interesting thing in this data is that EQT shows up. Why? They’re selling the gas. They’re not buying the gas. Well, it turns out that their agreement with the LNG export terminal is actually what’s called a “tolling agreement,” which means EQT is taking on the risk of running that gas, of paying a company a fee to run the gas through their export terminal and sell it on the open market.

Another interesting conclusion: in Washington, the industry has really sold LNG exports as a way to help American allies in Europe. We found that that is greatly exaggerated. The vast majority of these contracts are being held as what they call “portfolio players” in the industry, which are essentially just big oil commodity traders that have a freedom to sell gas to whoever can fetch the highest price. In times of great need in Europe, that’s going to be Europe. Most of the time, in the next 30 years, it’s going to be Asia, where the demand really is.

Part III: What do LNG exports mean for ratepayers in Pennsylvania and beyond?

Key findings:

- LNG exports and an increasing reliance on natural gas-fired power generation have driven sharp increases in residential gas and electricity prices.

- Rising energy costs place a greater burden on low-income households and households of color due to historical inequities in housing quality and efficiency. Over 1 million Pennsylvania families have an energy burden that exceeds 10% of their household income.

- Rising utility bills have led to a record number of involuntary service terminations and have significantly increased the number of Pennsylvania households lacking safe heat during winter. In addition to health risks and unsafe home temperatures, energy insecurity contributes to evictions, homelessness, and reduced access to public and private housing.

Joanne Kilgour: Thanks so much, Alan. Liz, your work has focused on how residential utility and energy matters affect low-income consumers. And you’ve seen firsthand how many of the impacts are already reaching these households and they’re bearing the brunt of rising energy costs in Pennsylvania. What can you share with us about how expanding LNG exports will further affect households struggling with already high energy burdens?

Elizabeth Marx: Well, let me see if I can tackle that. So the first thing to note, and this chart shows you, is that energy costs already account for a substantial percentage of household income. Low-income Pennsylvanians are paying between 10% and 30% of their income compared to 3% to 4% for middle-income households and even less for higher income households. We’ve got over 1 million Pennsylvania families that have an energy burden that exceeds 10% of their household income. It leaves very little for all of life’s basic needs.

I have to point out, every time that I get a chance to talk to folks, the importance of recognizing that households of color and additional low-income households have significantly higher energy burdens compared to white households. And this is a quantified disparity. It’s been studied up and down in multiple reports, huge data sets. And really it comes down to the quantified disparity driven by pronounced inequities in access to quality and efficient housing. So when you can’t invest in your housing or rather there hasn’t been investment in your housing, deferred maintenance because your ends aren’t meeting, meaning you can’t then invest in energy efficiency upgrades and insulation and fixing your roof and getting new windows, all of that creates a disparity. So when energy prices go up, you have to recognize that unless you are also fixing homes at the rate that is necessary—and Pennsylvania has some of the oldest housing stock in the country—you’re not fixing that gap. It’s only growing wider.

LNG is a relatively new factor driving energy prices in Pennsylvania and other states. It’s following an explosion of exports in 2016. Before that, we didn’t even really pay much attention to it. It was just generated in Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania gas is used by Pennsylvanians. And we thought, “oh, we’ve got tons of cheap gas,” and we were investing in infrastructure like crazy.

We put together what some of the price spikes were in 2022. Folks may remember that we had some severe price spikes in residential gas pricing in 2022 and into 2023, following the start of the Russia-Ukraine war and the rapid increase in LNG exports to Russia when they cut off energy supplies to the region.

What this chart shows is the default service price for residential gas service year-over-year, January 2021 through 2024. You can see the increase of roughly $60 a month through winter 2022 for the average residential gas consumers. And that’s that table at the very bottom. In 2021, the supply cost was about $40. Fast forward to January 2023, we were almost at $90. And then it went back down slightly in 2024 to $42.

What’s not depicted here, importantly, is that electricity pricing faced similarly dramatic increases, though they lagged a little bit behind. And that’s because Pennsylvania relies on gas to produce 60% of the state’s electricity.

Notably, based on the announcement yesterday from PJM Interconnection, our regional transmission organization, they’re going to fast-track gas generation and that will make our reliance on gas for electricity production even more leveraged, so these price instabilities will continue.

I do want to make sure folks are keeping in mind that this is the supply charge, not the total bill. There’s also the distribution cost and those have also been increasing exponentially, both for gas and electric infrastructure buildout, and that makes up another 40% to 60% of your bill.

These numbers are just for the actual gas that you’re consuming, not the whole bill distribution cost.

What are the numbers in terms of rising energy costs? Rising energy costs and the resulting rise in energy insecurity is, of course, driven by a number of factors, but LNG exports are perhaps, right now, the number one factor driving instability in wholesale gas and electricity markets, which is forcing Pennsylvanians to essentially compete with other countries for gas that’s extracted in our backyards.

In 2023, following the spike in energy prices that I just discussed, we saw terminations, which lag behind the price increase. The price increases, then folks fall behind on their bill. There are a number of protections, but as that catches up, we saw a tremendous rise in terminations. Over 330,000 households in 2023 lost gas and electric service. That year, involuntary gas terminations increased 40% year-over-year. Low-income families bore the brunt of that impact. And when you look at what the impact on low-income terminations were, that increased 60% year-over-year for households with income below 150% of the federal poverty level.

The lag was a little bit further for electricity termination rates because the increase in winter 2022 into winter 2023 didn’t hit gas prices until we were almost to the following winter. But through the end of 2023 and into 2024, we also saw an increase in electricity disconnections. You can draw a straight line between the instability we saw in the gas markets and this increase we’ve seen. The spike in the gas prices in winter 2022 and 2023, they weren’t an anomaly. We had a temporary reprieve because of the LNG export pause that’s being discussed, but the new administration has done, essentially, an about-face. EIA revised its cost projections into 2026, noting the increase in LNG exports, and they are predicting a substantial increase in 2026. We are anticipating we will see similar spikes in terminations prolonged.

What happens to families in the Appalachian region? Well, I can tell you what happens to families in Pennsylvania: this winter we had 24,000 households enter winter without safe heat. This is a record number. I’ve been at the Pennsylvania Utility Law Project for 12 years. I have never seen a number that high. It’s usually 20,000 or below.

When they did the re-survey recently, by February 1st, we still had over 16,000 families without safe heat in their home.

Lastly, I just want to put a finer point on the consequences of high energy prices on families and communities. Some of those impacts are obvious to folks. Your food spoils in your fridge. You’re exposed to unsafe temperatures in your home. You can’t take a hot shower. But energy insecurity also causes a range of other short- and long-term impacts on physical health, child development and learning, family unity. We have involvement of children and youth services; we have transfer of custody from one parent to another. Following an involuntary termination of utility service, eviction, condemnation, blight is often quick to follow, and unresolved utility debt can make it really impossible for a family to get and maintain public housing or even private housing, which will often use utility records as a reason to deny housing to an applicant.

So the impacts of high energy prices really do reverberate throughout our economy. They impact local businesses, they impact workers, they impact nonprofits who are providing services, they impact government and industry. And in 2023, as the high prices hit, I’ll say my office was fielding calls from large, multi-family subsidized housing providers wondering how they’d remain solvent as energy prices were eclipsing the amount that they are allowed to charge in rent because of housing subsidization. So even things like the availability of public housing, which is already at crisis levels, are impacted.

These are costly consequences and they’re destabilizing for families and communities. These costs really have to be part of the overall calculus in determining what the true impact of increased LNG exports is on our communities going forward.

Part IV: LNG exports have failed to deliver on promises of local economic growth.

Key findings:

- Many policymakers view the negative impacts of LNG expansion, like rising energy costs as necessary trade-offs for overall economic prosperity.

- But data shows that natural gas expansion in Appalachia has not delivered promised economic benefits to local communities.

- Instead, it has contributed to job losses, stagnant wages, and population decline, contradicting claims that LNG expansion promotes regional prosperity.

Joanne Kilgour: Thank you so much. And we really appreciate you being here, Liz. I want to take just a moment to share, for those who may not be familiar with Liz and her whole team at the PA Utility Law Project, that they work absolutely tirelessly to help low-income families deal with the many impacts of energy insecurity that she spoke about in her last slide. And I think one of the things that is less visible in spaces of environmental advocacy is that real, direct human impact on low-income families. It’s absolutely critical in my view that we remember that there’s a very near-term consequence. It shouldn’t have to take lawyers to defend people in order to have safe heating, full stop. It should not take lawyers to do that, but it does. And so Liz, I just wanted to thank you and your whole team for the work you do for Pennsylvania.

Sean, Liz talked about some of the direct economic consequences for ratepayers. I’d love it if you could tell us a little bit about the broader economic context. So many elected officials and other decision-makers argue that expanding LNG exports is necessary to increase jobs and improve local economic outcomes. But your research tells a different story. Could you tell us what your research says about the validity of those claims?

Sean O’Leary: Yeah, I will. And thank you for having me. You know, this is a very sobering moment because the dire consequences that Liz just described so vividly, and looking ahead to the effects on pricing that Alan and Eric talked about, those effects, as bad as they are, are often seen as often as almost necessary evils by many of the policymakers who promote LNG expansion. That’s unfortunate because they make that claim, they justify those effects on the grounds of general economic prosperity.

The sad fact is that, as ORVI has documented in a series of reports colloquially known as the Frackalachia reports, we know that expansion of the natural gas industry in Appalachia, far from being accompanied by improvements in quality of life and in economic opportunity, has brought exactly the reverse.

I just want to throw a few quick numbers at you to give you a sense of what we’re talking about. Between the year 2008, which was at the very, very beginning of the Appalachian natural gas boom, and 2023, the US economy grew in nominal GDP by about 87%. And GDP is, for many people, sort of the default measure of economic prosperity. What’s striking is that if you look at the 30 counties in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia that produce over 95% of all Appalachian natural gas, those counties actually outperformed the US economy by about 15%. They actually saw stronger GDP growth than the nation as a whole.

But when you look at the local measures of prosperity—the facts on the ground that hit people’s lives, like how many jobs are there? How much is income growing? How much is population growing?—in every single case, what we see is a region that, far from prospering in response to the expansion of natural gas, has been going in precisely the opposite direction. Take a look at jobs, for instance, which, for many people, especially politicians, is kind of the go-to statistic. We were wringing our hands a few months ago during the presidential campaign about how many jobs are associated with fracking and how important that is in swing states like Pennsylvania.

The truth of the matter is that the number of jobs in the counties that produce 95% of natural gas have actually declined since the beginning of the natural gas boom. Meanwhile, in the US as a whole, they’ve increased by 14%. Despite the fact that Appalachia and the Frackalachian counties are actually outperforming the US for GDP growth, they’re not only underperforming for jobs, they’re actually seeing absolute shrinkage in the number of jobs. And what’s even worse is that underneath the jobs is the labor force. Labor force is important because when companies look to expand, they look for places with strong talent pools, large numbers of workers who can come do the jobs. But the number of people in the labor force in the Frackalachian counties has actually declined by almost 6%. Meanwhile, it’s expanded in the US as a whole by 8%. And similarly, incomes in Frackalachia have only grown at about three quarters the rate of the US economy. And then finally, population. Population nationally has grown by about 10%. In the Fracklachian counties, it has shrunk by 3%.

So what we see is this pattern that sometimes we’ve called the “resource curse” of a place that’s very rich in natural resources and in trade based on those resources which, nonetheless, does not experience improvements in quality of life or in overall prosperity. And that sadly is the case for Frackalachia.

We hear policymakers talk about the importance of developing new markets for Appalachian natural gas. They use that as a justification for promoting export terminals in Philadelphia or the Shell cracker plant, which was generally identified as the biggest economic prize of the entire Appalachian natural gas boom, But a report by Eric DePlace, who’s part of this panel, just a week ago pointed out that the economy has gone absolutely in reverse in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, where the Shell plant is located.

The bottom line is that the expansion of Appalachia’s natural gas industry has, in addition to not working to the benefit of consumers who have to pay for gas and pay for electricity, it also has not worked to the benefit of communities where the work is being done—either in terms of jobs, in terms of income, or in terms of population.

So thank you, Joanne, and I’ll throw it back to you.

Part V: Q&A

Key Findings:

- Companies like Saudi Aramco often act as “brokers” within the gas industry, buying and reselling gas globally—and sometimes at higher prices—which can drive up costs for consumers in Appalachia and beyond.

- Increased reliance on natural gas for electricity generation ties US consumers to global gas markets, leading to higher prices. Projected increases in natural gas prices could result in a 10-15% rise in electricity bills, per EIA.

- Energy producers anticipate rising gas demand from data centers, electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure, and transportation, which could further drive price increases.

- Communities can mobilize by participating in public comment proceedings, engaging with utility commission hearings, and voicing concerns to legislators. Consumer impacts, especially rising energy costs, are not widely discussed, making advocacy crucial.

Joanne Kilgour: Thanks very much, Sean. So we have some prepared questions, but I also see that we have some great questions open in the Q&A.

One question was, why is Saudi Arabia buying gas? The visual of the growth in exports and the volume of gas purchased by Saudi Arabia—what accounts for that?

Eric de Place: So, the Saudi Arabian petroleum company Saudi Aramco that’s listed in Alan’s chart, like many of these other large oil and gas companies, they have multiple lines of business. One of the things they do is essentially act as brokers for commodities like oil and gas. They will buy up large quantities of gas from anywhere, really, where they can buy it—including homegrown stuff from Saudi Arabia, including stuff from the United States—and then they will resell that to buyers.

So yes, Saudi Arabia produces more gas than is consumed within the country of Saudi Arabia, but there’s also a separate business line where you become both a buyer and a seller of gas to maximize profits.

It’s a good question and an interesting illustration of the fact that, for a while, the gas industry was saying that we need to export a lot of gas to our dear friends in Western Europe to help them keep the heat on so that they can get free from Russia’s grasp. And while that wasn’t completely untethered from reality, it was mostly untethered from reality.

In fact, what’s happening is that a lot of the gas actually gets exported, purchased by big brokers like Saudi Aramco, and then resold to the highest bidder. And that highest bidder part is really the sharp teeth of what’s going on here because it means that a low-income household in Pennsylvania is, in effect—although there’s a chain here—bidding against the highest price that Saudi Aramco can sell that gas for anywhere in the world. That’s where the really nasty consequences of the industry come home, strictly from an economic standpoint, for local households. There are a whole set of environmental concerns, as well.

Alan Zibel: Yeah, I totally agree with all of that. The only thing I would add is that foreign investors in the Gulf Coast LNG terminals are very, very common. There’s Saudi money, there’s UAE money, there’s Asian money, and that kind of gives the lie to the industry argument that says, “oh, this is good for GDP; this is good for this aggregate measure of the economy.” In reality, the profits are being pulled out by extraordinarily wealthy investors in Saudi Arabia, in the UAE, around the world, and local rich guys like Toby Rice, too.

Joanne Kilgour: Thank you both. We also have a question about the role that gas’ share in the electric-generating sector might play. For the projected impact of LNG expansion on gas, consumer, and electric prices, what assumptions does it make about gas’ share of electric generation going forward? If federal and state incentives start prioritizing gas as the reliable resource, what does that price impact look like?

Elizabeth Marx: From our perspective, we think it’ll have a big impact. The more we are reliant on gas, the more that we are competing with Saudi Arabia, China, and Europe for pricing, the higher electricity prices are going to go. There’s a very direct connection there. Based on the way that we procure energy in Pennsylvania, the way not just gas prices go from wholesale purchases, but also how we purchase electricity prices for consumers, it’s going to be baked in. The more we’re relying on gas to generate our electricity, the bigger the problem. Certainly PJM’s announcement yesterday is problematic for this and directly tied to the LNG issue.

Sean O’Leary: Alan, you earlier mentioned that the EIA has upped its estimation of natural gas prices to about $4.20 in 2026. What I wanted to point out is that that’s an increase of about a third in the price of natural gas. Overall, in our region, the supply of natural gas to the electric power industry represents about 40% of the cost that you see in your electric bill.

So in very, very round numbers, what we’re seeing is the price increase that EIA forecasts is very likely to result in something on the order of a 10% to 15% increase in electricity bills, quite apart from the effect that the LNG export issue is likely to bring to the table. So we are in an environment where we’re seeing a number of trains coming together at a single intersection here. The expected expansion of demand for electricity from data centers and from transportation electrification happens to be intersecting with added demand issues associated with LNG exports. And so, yes, that all could come together and have a much larger impact on prices in our region.

Alan Zibel: I would say that, just building on what Sean says, if you look at the producers’ SEC filings, their investor presentations, they are very bullish on natural gas prices. So they are excited about demand from data centers, from transportation, from EV electrification. They think that this could be very good for their business, so that should tell you everything you need to know.

Joanne Kilgour: Now that we have this information, what do we do with it? Once we know something, how can we activate it? Given your research and experience, what are the most effective ways that grassroots leaders can use the findings to mobilize communities, influence media, decision-makers, and disrupt the LNG expansions locally?

Elizabeth Marx: I’d say, for one, there’s this comment proceeding happening on the LNG policy. Filing comments and organizing groups to file comments, pointing out the price impact, lifting up stories of individuals in your community who are impacted by higher energy prices, showing up at public utility commission hearings.

We litigate rate cases often and there are always public input hearings. Sometimes it’s just the lawyers and the judge looking at each other, waiting for the public to show up. Figuring out when those hearings are coming and talking about those forces—this is not something that folks hear about. It’s kind of operating over here— this is a big, macroeconomic policy that’s having a microeconomic impact on our communities, and people don’t make that connection. Making that connection, talking to your legislators, is really important.

I’ve started talking to legislators about this and they told me that they have not heard from any consumers about the consumer concerns. There are a lot of folks out there talking about the environmental concerns of expanded LNG and the risks of LNG. But in terms of consumer impacts, they’re not hearing from folks. One really important thing is to start talking to your friends, your neighbors, your elected officials. Showing up at public input hearings to say, “We know that this macroeconomic policy is having a microeconomic effect on our families and our communities. Here’s what’s happening and here’s what we’d like you to do about it.”

My office is always happy to talk with consumers who want to get involved. In these kinds of proceedings, we do that. We help community groups. We help others to figure out how to verbalize what it is that they want to say and point out the channels where they could say it.

Joanne Kilgour: Thanks, Liz. I’ll add just a few things—in addition to the proceedings that Liz was referencing, we do see quite a lot of impact from earned media. Sharing your perspective through opinion pieces or other kinds of written materials and the opportunity really just to talk about this information in a way that will make sense to you and your neighbors. I know that a lot of times, as much as we try to be accessible, our work can still be pretty wonky.

And so we need a lot of translators out there in the community taking the things that we say and making them make sense to families, neighbors, staff of elected officials, elected officials themselves and And other decision makers, really. There are a lot of people who are trying to handle so many issues and this may not be on their radar.

Or, as one of our audience members mentioned, $122 might not sound like that much money to you, but if you learn that that’s going to be the make-or-break cost between a family having safe heat or not, then maybe you care, even if it’s not going to impact your pocketbook. Those are all things that can be done to try to activate this research and help bring it into the world in a way that it can have an impact.

In these final seconds, I’d like to just ask you all to join me in a warm thank you to our panel: Eric, Allen, Liz, and Sean, we so appreciate your time and we know that this is not the last we’ll be hearing from you all on this issue. Thanks so much.