Key Takeaways

- Appalachian ethane is already fueling a petrochemical buildout in the Gulf Coast and around the world.

- The region’s production of natural gas liquids, including ethane, is forecasted to grow faster than any other region of the US over the next 30 years.

- New infrastructure—pipelines, compressor stations, fractionators, and petrochemical plants—is locking in demand for NGLs, driving more fracking for both gas and gas liquids.

Although the world is awash in plastics and other petrochemical products, the industry is planning for decades more growth. If its expansion plans come to pass, much of it will be driven by Appalachia, the very region where the industry got its start. Rebecca Altman’s new essay, “Upriver,” provides an insightful history of the Ohio Valley’s history with petrochemicals, setting the stage for an analysis of what may come next.

Today, the Marcellus-Utica shale gas fields of Appalachia serve as a major source for natural gas liquids (NGLs), the class of hydrocarbons that includes ethane, propane, butane, isobutane, and pentane that is often found commingled with methane in “wet” gas wells. These Appalachian Basin NGLs are today transported throughout the county and increasingly are exported worldwide to fuel a global petrochemical buildout.

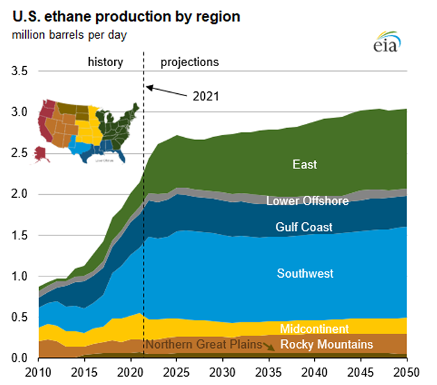

Ethane is the most abundant and economically important of them. It is used almost exclusively to produce ethylene, which is then turned into plastics. (By contrast, much of the propane is burned for heating, although a substantial amount is used as petrochemical feedstock.) Ethane production in the US has nearly tripled since 2008 to reach about 2.1 million barrels per day in 2021, an increase the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) attributes to growing demand for petrochemical feedstocks.

Although EIA does not maintain state-by-state data, analysts estimate that Appalachia currently produces nearly a quarter of the nation’s total. The region’s production has been growing rapidly: total US NGL production roughly doubled from 2010 to 2018 while it grew by six-fold in Appalachia.

Appalachia’s growth looks set to continue. In its most recent comprehensive forecast, the EIA projects that NGL production from the East region, which is dominated by Appalachian production, will grow dramatically in both absolute and relative terms.

In fact, according to EIA, the East region, which includes the Appalachian Basin as well as the Utica and Marcellus Shale formations, will contribute more than two-thirds of total US growth in NGL production between 2017 and 2050, with a steep rise in production in the next few years.

In 2020, the East region accounted for just 14% of total US ethane production, but EIA projects that by 2050 Appalachia will account for 32%. Meanwhile, the share produced in the Southwest region—which has historically produced the most NGLs—is expected to essentially plateau from 37% to 36%. The latest EIA figures from August 2022 confirm in broad strokes the agency’s more detailed analysis from 2017, which showed long-term growth US NGL production—largely attributable to the East region.

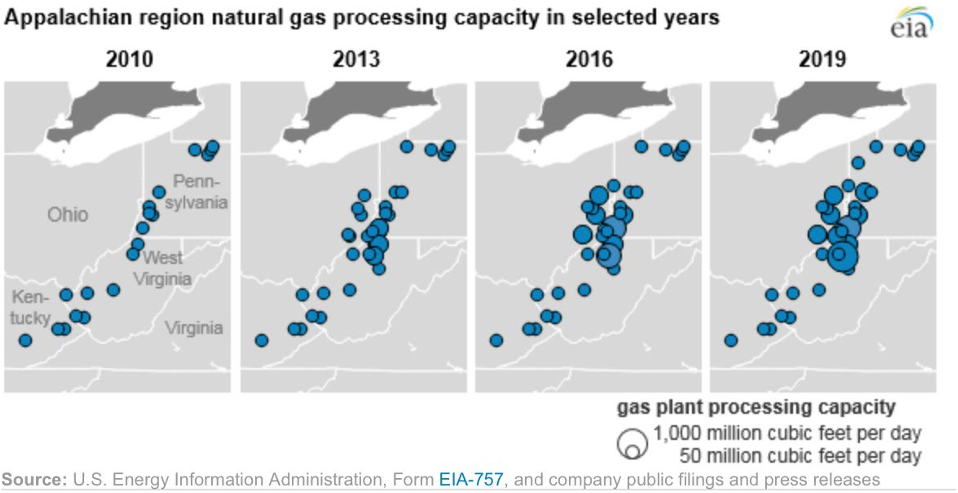

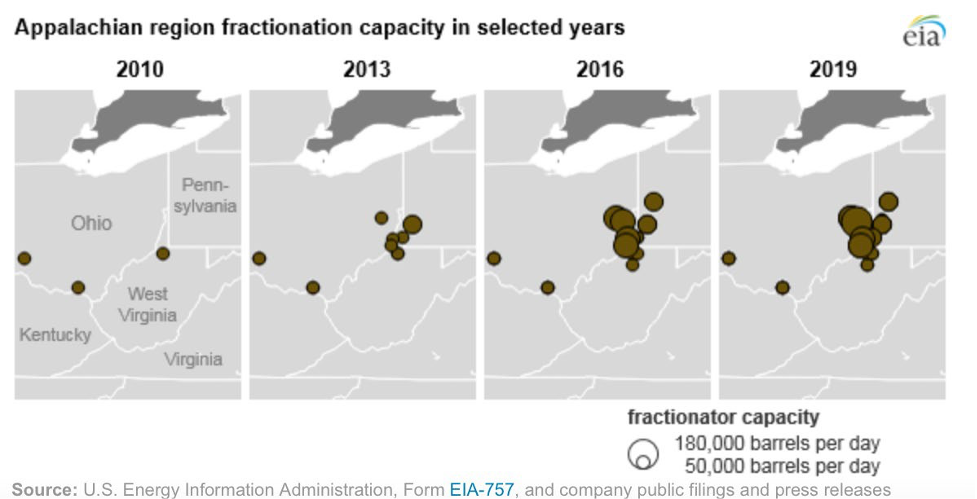

The growth in Appalachia’s ethane production is enabled by a steady buildout in supporting infrastructure, including an array of fractionators, pipelines, compressor stations, storage facilities, and export terminals, that help bring NGLs to market. In the Appalachian region, unlike other producing regions, all liquids extracted are fractionated locally. In fact, between 2010 and 2016, EIA estimates natural gas processing capacity in Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia has increased by over 800%, growing from 1.1 Bcf/d to 10.0 Bcf/d.

Prior to the buildout in fractionating capacity, most Appalachian ethane was “rejected,” meaning that it remained commingled with natural gas and was burned as fuel, rather than being separated out for sale as a feedstock. But rising prices in domestic and increasingly in global markets made it profitable for Appalachian producers to separate out ethane for use as a petrochemical feedstock.

Additional factors influence the projected growth in Appalachia’s NGL production. In a 2018 report, EIA predicted that after 2022, growth in gross natural gas withdrawals would slow and the composition would become progressively drier making ethane scarcer and recovery more profitable.

Demand for Appalachian ethane is being driven by the petrochemical industry, especially the construction of new ethane crackers—big petrochemical plants that manufacture ethylene, which is in turn used to make plastic products. According to the American Chemistry Council, nearly 350 fracking-enabled petrochemical projects, with a total price tag of more than $200 billion, have been planned or completed since 2010. According to EIA, just three new crackers—Baystar and Gulf Coast Growth Ventures in Texas and Shell’s Pennsylvania Petrochemical Complex—will increase US capacity to produce ethylene by 11%. EIA forecasts that these additions to ethylene capacity will cause US demand for ethane as a feedstock to grow to 2.1 million barrels per day by the fourth quarter of 2022, up from 1.5 million in the first quarter of 2021.

There is reason to think the growth will continue. Global ethane demand is forecasted to be up 4.2% this year, according to the International Energy Agency. And, an April 2022 report on the petrochemical industry by McKinsey finds polyethylene demand has remained resilient despite the pandemic and is actually growing beyond pre-pandemic levels.

Appalachia’s NGL infrastructure buildout is fueling petrochemical buildout domestically and around the world.

As the Department of Energy noted in a June 2020 report, with energy infrastructure expansion in Appalachia, manufacturers and consumers in the industrial Midwest, New England, and the East Coast have an opportunity to benefit from low-cost energy and energy-related products and petrochemicals produced in Appalachia. As new infrastructure—a pipeline or a petrochemical plant—comes online, each project hypothetically “locks- in” another increment of NGL demand.

According to industry backers, one factor driving Appalachian ethane production is Appalachia’s proximity to the domestic customer base for chemical derivatives and finished manufactured products. As the backers of Shell’s Pennsylvania Petrochemical Complex like to note, the center of the NGL production area is within a day’s drive of 70% of the downstream manufacturing demand for polyethylene resin and within 500 miles of more than 40% of the United States population. So far, however, these factors have not been sufficient to drive the construction of additional ethane cracker plants or plastics manufacturers in Appalachia.

Apart from the Shell cracker, virtually all of the ethane produced in Pennsylvania and West Virginia is either shipped to other parts of the US or exported abroad. Over the past year, about 69% of ethane produced within the “PADD 1” region as designated by EIA (the eastern seaboard, where Pennsylvania and West Virginia dominate ethane production) was shipped to or through “PADD 2” (the Midwest, including Ohio) by pipeline, while 27% was exported to other countries. The remaining sliver was either used or stored within PADD 1.

Today, there are five ethane pipelines originating in Appalachia with a combined total capacity of 422,000 barrels per day that deliver NGLs to nearly all points of the compass. Energy Transfer’s Mariner West Pipeline and Kinder Morgan’s Utopia Pipeline each deliver about 50,000 barrels per day of ethane to destinations in Canada, just over the Michigan border near Detroit.

Meanwhile, the ATEX Pipeline, which may soon be expanded, moves 145,000 barrels daily from western Pennsylvania through Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and onward to reach a large storage facility in Texas. Some Appalachian ethane may be delivered to petrochemical facilities along the ATEX route, including the Westlake Vinyls plant in Calvert City, Kentucky and the El Dorado Chemical Company plant in Union County, Arkansas. The remainder is shipped directly to the NGL hub at Mt. Belvieu, Texas. The NGL hub at Mt. Belvieu in turn feeds ethane and other NGLs to nearby petrochemical facilities in the Gulf Coast region.

The fourth and fifth, and perhaps the most significant NGL pipelines are within the region: the troubled Mariner East system, which serves a large ethane export terminal in eastern Pennsylvania with large volumes of ethane, along with other products like propane and condensates. The recent completion of Mariner East 2X enlarged the system’s capacity to ship ethane from fracking basins in the Ohio Valley to export on the Atlantic Ocean to approximately 350,000 barrels per day.

Appalachia’s NGL production is already fueling a global petrochemical buildout

The industry is producing far more ethane than US plants can use, so firms are selling growing amounts overseas at bargain prices. As a result, exports account for an increasing share of total ethane demand. In 2013, the US exported none of its ethane, but by 2020, it was shipping about 16% abroad. Canada has been importing large volumes of US ethane since 2014. And in 2016, the US began exporting ethane gas by tanker to overseas destinations.

Overseas ethane exports were made possible in 2016 thanks to a new fleet of vast, custom-built ships capable of hauling ethane gas across the Atlantic, to plastics makers in Britain, Norway, and Sweden. INEOS, with ethane crackers in Scotland and Norway, became the first European company to contract for US ethane feedstock in 2012, when it agreed to import Appalachian ethane via the Mariner East pipeline system and the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex, a massive export terminal in southeast Pennsylvania.

By 2021, the US exported to eight countries: Canada, China, India, the United Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, Mexico, and Brazil. Overall, US ethane exports have skyrocketed 585%, from 800,000 tons in 2014 to more than 5.5 million tons in 2020, according to ICIS, an energy and chemicals analysis company.

US ethane now supplies 10% of European ethylene production, and a proposed new ethane cracker plant being constructed in Antwerp, Belgium would increase that to nearly 20%, according to energy and chemicals consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. INEOS, the same global petrochemical company that started shipping fracked ethane across the ocean from the US to Europe, is behind the proposed plant, which is facing opposition from local environmental groups. According to Steven Feit, an attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, the steady and increased supply of US ethane—much of it coming from Appalachia— “is taking the US petrochemical expansion and bringing it to Europe”. Indeed, in recent years INEOS expanded two of its cracker plants—one each in Norway and Scotland—to provide more ethane storage to feed those plants and upgraded the sites to handle receipt of the ships carrying US ethane. And the Mariner East 2 pipeline is slated to transport even more ethane to Marcus Hook, much of which is likely to be exported to existing and future contracts with European petrochemical companies.

As gas processing and transport capacity increases along with the projected growth in Appalachia’s ethane extraction, Appalachian NGLs have the potential to fuel future petrochemical buildout in the United States, Canada, Europe and beyond.

Thanks to Molly Kiick who provided valuable research assistance and to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, which provided important data and analysis.

Technical note: It is difficult to determine the fate of Appalachian ethane produced in Ohio, or the destinations of Appalachian ethane shipped through the Midwest. The US Energy Information Agency groups Ohio into PADD II, a region that encompasses several major oil and gas producing areas, including western Appalachia (Ohio), the Bakken Shale (North Dakota), and the SCOOP/STACK formations (Oklahoma). In addition, a number of “Y-grade” pipelines carrying a mix of NGLs either originate in, or traverse, PADD 2, complicating the analysis. Still, it is possible to make reasonable estimates based on industry reports and assessments of infrastructure.