Earlier this month, we provided an explainer of the $4.7 billion federal orphaned well program that was included in the federal infrastructure legislation (the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021) and what that meant for states in the Ohio River Valley. To recap, the states of Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia could receive a combined $1.1 billion in federal orphaned well funding over the next decade. However, these funds will only be enough to decommission or close about a third of the documented orphaned well inventory in these states, not to mention the hundreds of thousands of additional orphaned wells that are undocumented.

This post provides a list of six recommendations to meet the program’s goals of reducing methane emissions and other hazardous pollution while providing well-paying jobs by plugging thousands of orphaned wells and cleaning up well sites. On top of these goals, it is imperative that this federal program provides a pathway to a long-term solution to the abandoned well crisis, ensuring all wells are cleaned up.

Last week, the US Department of Interior issued draft guidance for states on the Initial Grants with regard to the application process and best practices. Some of the recommendations below address this Initial Grant guidance, while others are recommendations for the program at large. These recommendations can be adopted by the Department of Interior (DOI) via rule-making or guidance to states by states themselves. These recommendations also build upon a memo from Megan Milliken Biven, an oil and gas expert at True Transition, that was submitted to White House Senior Advisor and Infrastructure Coordinator Mitch Landrieu. They also reflect comments submitted to DOI by ORVI and others regarding their draft guidance for states on the Initial Grants.

1. Establish a National Definition of “Orphaned Well”

A clear and consistent definition of “orphaned well” is needed to protect taxpayer dollars and ensure that wells most in need of federal funding are prioritized for plugging and well site restoration. US legislation defines an orphaned well as one “for which no operator can be located” with respect to federal and Tribal lands; however, for state or private lands, it adopts “the meaning given the term by the applicable state” for a well “eligible for plugging, remediation, and reclamation.” There are 32 states that produce oil and/or gas in the United States, and 38 states are members of the Interstate Oil & Gas Compact Commission. Each state has a different definition of what constitutes an “orphan[ed] well” and many have no statutory or formal definition at all or use different terminology. For example, Ohio and West Virginia do not statutorily define an “orphan(ed) well,” but do define an “abandoned well.” This means states have lots of wiggle room when adding an abandoned well to an orphaned well list.

Because states have more than 30 definitions for or approaches to what constitutes an orphan[ed] well, it is nearly impossible to certify that federal orphaned well funds will be used for their intended purpose. While the legislation requires the federal government to “determine the identities of potentially responsible parties associated with the orphaned well…and to make efforts to obtain reimbursement for expenditures to the extent practical,” it fails to prevent states from using federal funds to plug wells with known solvent operators if the state classifies those wells as orphaned.

According to a 2020 IOGCC survey that included 25 states, 78 percent of documented orphan wells had known operators. Of the 34,250 documented orphan wells in West Virginia and Pennsylvania, nearly 24,000, or 70 percent, had known operators. While many of the identifiable operators of these orphan wells are defunct or went out of business decades ago, some are still operating or have been bought out by bigger companies. For example, West Virginia lists 4,588 unplugged abandoned wells with no known operator (i.e., orphaned) in their oil and gas database, but dozens of those orphaned wells have operators that are still in the business today.

Ross and Wharton Gas Company, which is based in Buckhannon, WV and owned by Mike Ross, has 15 wells that are listed as orphaned in the WV Department of Environmental Protection database. Southwestern Energy, which owns over 1,000 wells in West Virginia and is one of the state’s largest gas producers, owns 10 wells on West Virginia’s orphaned well list through subsidiaries. EQT, the third-largest operator in West Virginia, owns 9 wells listed by the WVDEP as orphaned wells through its subsidiaries (see bottom of post for details).

A national definition of an orphaned well that is used for state jurisdictions will ensure federal orphaned well plugging funds do not go to plugging wells and restoring well sites that have solvent owners. This will protect taxpayers and limit the risk of moral hazard, where oil and gas operators may anticipate that the federal government will pay for the plugging and remediation costs associated with their wells. To avoid this moral hazard, federal orphaned well funds should only be used to close wells where bonds have been forfeited and the owners or any subsidiaries are insolvent. We recommend that the Department of Interior use a similar definition of orphaned wells for state jurisdictions as they do for federal and Tribal lands: “a well for which no operator can be located.” Alternatively, DOI could create a certification process for each orphaned well plugged using federal funds. This could also include penalties if it is discovered that federal funds were used to plug wells or restore well sites with solvent owners.

2. Establish a National Database of Oil and Gas Wells

To administer the orphaned well program, it is imperative the federal government establishes a national database that combines state well datasets. This will not only provide accountability and transparency to the public on the wells being plugged with federal funds, but will also help DOI to administer the program effectively and efficiently. Last year, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) advised DOI to integrate its three data systems to oversee oil and gas development on leased federal lands into one management system. DOI could also use this as an opportunity to integrate oil and gas well data from state and Tribal lands, as well.

Currently, 28 states use products from a Risk Based Data Management System (RBDMS) developed by the Ground Water Protection Council in partnership with the US Department of Energy. The RBDMS provides interactive mapping, a storage system for oil, gas, and underground injection control facilities and activities. The RBDMS also provides state oil and gas regulatory agencies with data accounting, such as permitting, well completion, production, and more. Moreover, the system is used to facilitate public access to state-held industry and regulatory data. DOI could also utilize the RDMS to develop a national database for all active and inactive wells in the United States.

A national database could not only include well data but also provide a risk-based assessment for each orphaned well and an accounting of the costs of plugging, remediation, and reclamation for each well. The national database could be on a public website that also includes other information about the federal orphaned well program, including contracts, information by state, Tribe, and federal land, number of jobs created, and the distribution of funds.

3. Establish National Decommissioning Standards

The typical lifespan of a plugged well is largely unknown. However, it is generally understood that wells plugged before 1950—which make up a large share of orphaned and legacy wells—are considered unplugged or not plugged by modern standards. Prior to the 1950s, wells were either not plugged at all or plugged with very little cement. In some instances, wells were plugged with wood, brush, rocks, or paper and linen sacks. After 1952, when the American Petroleum Institute standardized plugging procedures and cement composition for wells, cement plugs were more commonly adopted.

For the most part, the basic technologies for plugging and abandoning (P&A) wells have not changed significantly since the 1970s. Cement is still the primary material used to plug wells. The problem with cement, depending on its type, is that it can shrink and crack and cause leaks into adjacent zones and the atmosphere. The cement used in various plugging methods can also become contaminated by drilling fluid. Recent research by Mercy Achang and others concluded that “next-generation P&A is likely to use new materials” and that innovations and advancements will be critical “to achieve permanent P&A in the future.”

According to a 2011 report by the National Petroleum Council, “little actual research has been done on the materials and procedures for plugging oil and gas wells.” The National Petroleum Council finds that “lack of progress in P&A practices is attributable to absence of a long-term vision, and inattention to corresponding research, that recognizes the benefits of P&A to oil and gas development projects.” The report finds that “most wells are plugged at the lowest cost possible” because they are an “afterthought” that provides “no return on investment” for oil and gas companies. While states have different regulations regarding plugging and abandonment, there is no uniform or gold standard. This program provides a good opportunity to convene a working group to make recommendations to states to ensure that they are using the most up-to-date techniques, materials, and technology for P&A to ensure plugs last as long as possible. The working group could also explore best practices for remediation and reclamation of well sites, as well as ideas for redeveloping well sites.

4. Require Inspections of Orphaned Wells

DOI should mandate that orphaned wells plugged with federal funds be inspected before and after well and wells sites are decommissioned. This will help ensure that plugging contractors use best available practices that improve safety and health. The inspections should also include methane measurements and proper tagging of wells when they are decommissioned. Requiring inspections is also critical to building up state-level oil and gas oversight capacity.

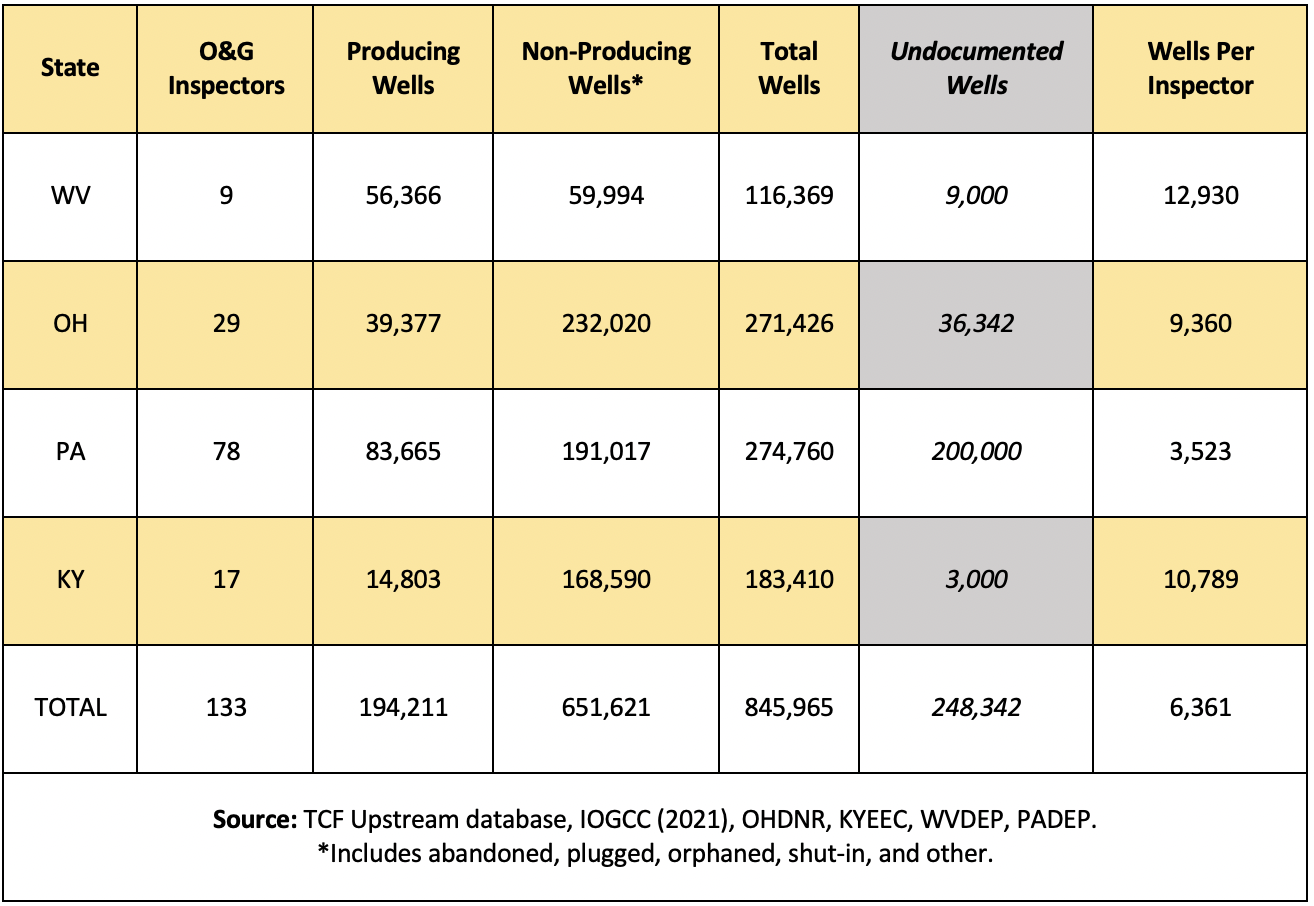

As the table below shows, the four states of the Ohio River Valley region—Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia—have just one oil and gas inspector for every 6,000 wells, on average. West Virginia has just one inspector for every 13,000 wells. West Virginia had 13 inspectors in 1996, and about 20 in 2012, compared to just 9 in 2022. Ohio has 29 inspectors, while Kentucky has 17.

In Kentucky, the number of inspections conducted per inspector has ranged from 631 in 2014 to 806 in 2019. In West Virginia, of the 5,695 inspections conducted in 2013, only 28 abandoned wells were inspected. In 2018, the WVDEP carried out 4,693 well site inspections and only 13 of these were abandoned well inspections. In Ohio, inspectors conducted approximately 28,000 site inspections. Using an average of 500 wells inspected per inspector, it would take inspectors in the four states an average of 13 years for inspectors to inspect each well (845,965). According to a survey of 19 states included in a 2014 report from the Groundwater Water Protection Council, 459 inspectors carried out about 269,000 inspections in 2013, about 586 inspections per inspector. These inspections are for well sites, so they can include multiple wells, various equipment, processing facilities, transmission pipelines or gathering lines. In Pennsylvania, inspectors carried out 25,883 inspections in 2020, an eight-year low, with approximately 78 inspectors. This is about 332 inspections annually per inspector.

This information makes clear that states have little capacity to inspect their respective well inventory in a timely fashion. This is especially true of abandoned and orphaned wells. A recent audit of West Virginia’s Oil and Gas Division found that “unless an operator applies for a well-work permit that would require an inspection, or a citizen files a complaint, the well site will go uninspected for potential hazards to the public and environment.” Requiring an inspection of orphaned oil and gas well sites prior to and after wells are plugged and well sites are restored will help ensure that states use their federal orphaned well funds on contracts that adhere to best practices, reducing the risk of waste (that the work will have to be redone) or inadequacy (work done in a manner that does not protect public health, safety, or the environment). It will also help encourage states to hire additional inspectors instead of outsourcing this work or not doing it all.

5. Establish Apprenticeship Programs and In-House Plugging Programs

One crucial item left out of the federal orphaned well legislation is investments for workforce training. While the number of jobs in the oil and gas industry (NAICS 211 and 213) has declined by 60,000 since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020, the industry is beginning to recover and has added more than 40,000 jobs over the last year. The runup in oil prices over the last three months also means that this job growth may accelerate, which could make it harder for states to find contractors to plug orphaned wells and increase plugging costs.

In light of these developments, and considering both the length of this federal program (10 years) and that most state oil and gas regulatory program will be plugging more wells per year over the next ten years than they have in the last decade, the creation of apprenticeship and training programs could help ensure that there is a workforce available to execute the work. Additional funding for workforce and safety training, including a federally recognized apprenticeship program, would also help bring new workers into oil and gas plugging and restoration work and build a larger qualified and skilled workforce.

Another avenue for states would be to create in-house plugging programs, which could lower costs, improve efficiency, and ensure that best practices are used to plug wells and restore well sites. While there would be significant upfront costs to purchase rigs and equipment, it would allow states to respond more quickly to emergencies from leaking wells and to quickly procure projects. Pennsylvania has used in-house public employees to perform abandoned mine reclamation for decades, and there is little reason why this could not be done with oil and gas decommissioning projects.

6. Establish Contractor Policies to Grow Local Economies and Promote Good Jobs

While federal legislation doesn’t include provisions regarding contractor policies, it is imperative that irresponsible contractors aren’t awarded state contracts with federal funds. This can be accomplished by ensuring contractors meet basic standards to bid on projects related to federal orphaned well funding, such as valid licenses and certification, compliance with federal, state, and local laws, having no history of business or labor violations, and meeting bonding and general liability requirements. The inclusion of a “Responsible Bidder” policy acts as an “insurance policy for taxpayers” by providing clear objective standards that contractors have to meet so unscrupulous contractors do not win bids that can drive up costs, reduce the quality of work, lower worker pay and benefits, and ultimately provide less investment in local communities.

A responsible bidder policy could stop oil and gas companies from bidding on projects when they have unresolved environmental violations. For example, oil and gas drillers with unresolved environmental violations should not be permitted to bid on plugging contracts. In Pennsylvania, the Department of Environmental Protection has made clear that these operators would not be awarded contracts to plug wells under the federal orphaned well program. Operators such as Diversified Energy, which is the largest well owner in Appalachia and the US, has purchased a well plugging company and has over 1,600 violations from PADEP over the last six years. Over 400 of these violations were for “failure to plug the well upon abandoning it.”

Included in the federal infrastructure bill is the inclusion of Davis-Bacon prevailing wage regulations for orphaned well cleanup. It is imperative that oil and gas regulatory agencies establish an active monitoring program and work with the US Department of Labor to ensure proper enforcement. This is especially important because many states do not have state prevailing wage laws for public construction projects.

One goal of the Biden administration and DOI is that this program can “drive the creation of good-paying union jobs.” The coal mining and oil and gas industry has low union density, with just 6 percent of workers represented by unions in 2021. To the author’s acknowledge, few, if any, oil and gas operators or plugging companies are unionized in Appalachia, with most unions engaged only in pipeline construction. One reason for this is contract size. Unions are not likely to be attracted to well plugging and restoration work unless the project contracts are over $1 million. In Pennsylvania, the largest contract awarded by the PA DEP for plugging wells over the last six years was just $250,000. Bundling contracts to include multiple well sites in a similar geographical area would not only increase the size of the contract, but also reduce costs and the time it takes to plug a well and restore a well site.

Another avenue to explore is project labor agreements, or PLAs. The White House underlined the benefits of PLAs in a recent executive order requiring PLAs on projects above $35 million. The federal government could lower this threshold to $1 million for projects included in this program.

____________________________________

*To find these wells, enter the following API# into the WVDEP Oil and Gas Well Database:

Ross and Wharton Gas Company: 4704700018, 4700100106, 4701300258, 4709700001, 4704700024, 4709100053, 4700100371, 4704700021, 4704700005, 4704700004,4704700013, 4704700015, 4704700012, 4705100138, 4704700019.

Southwestern Energy (Viking International Resources, Virco, Triad Hunter). 4708500787, 4708502887, 4708500067, 4708505504, 4708505660, 4708703403, 4707300951, 4708502966, 4708701474, 4708501827

EQT (Subsidiaries: Carnegie Production, Eastern States, Trans Energy): 4708500430, 4701100103, 4709701834, 4704300046, 4707900088, 4710300271, 4701100230, 4701100101