The Ohio River Valley Institute’s recent report on the nearly complete failure of the Appalachian natural gas boom to deliver on promises of jobs and prosperity in the region’s major gas-producing counties triggered a great deal of blowback from the industry and its defenders. Industry lobbyists and advocacy groups and their allies in congress castigated the report, calling it “fake news” and a case of statistical cherry-picking.

What they did not and could not do, however, was dispute the report’s finding that, despite skyrocketing economic output (GDP), the Appalachian natural gas boom yielded anemic income growth, almost no growth in jobs, and was accompanied by an absolute decline in population.

Instead, they grasped for alternative statistics, desperately attempting to deflect attention from the facts. Still, the alternative statistics with which industry defenders try to distract us are worthy of examination because they provide an anatomy lesson in how they have, often successfully, misled the public and policymakers.

How a declining unemployment rate can be worse than a rising one

Industry spokespeople regularly cite declining unemployment rates over the past decade as evidence that the natural gas fracking boom has contributed to prosperity. Watch Ohio Oil & Gas Association Director of Public Relations, Mike Chadsey, try to dismiss the ORVI report’s finding of job losses in two Ohio fracking counties.

Mr. Chadsey made these remarks in an interview broadcast by WFMJ Channel 21 in Youngstown, Ohio. What he either didn’t know or chose to ignore is that there are two ways to reduce the unemployment rate — one good and one bad. The good way is to create more jobs. But, there is another way, which is actually worse for workers and for the economy than an increasing unemployment rate. That way is to drive people out of the labor force.

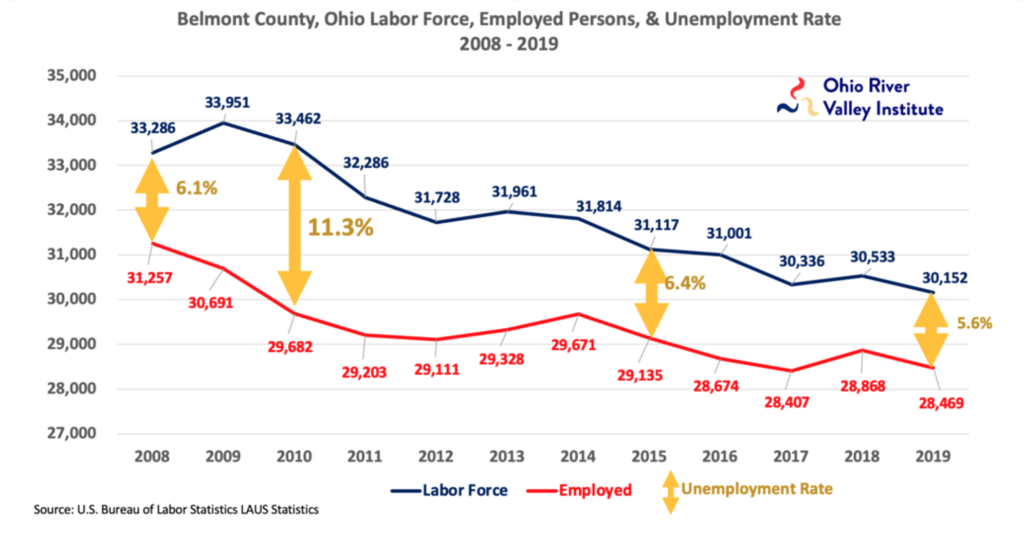

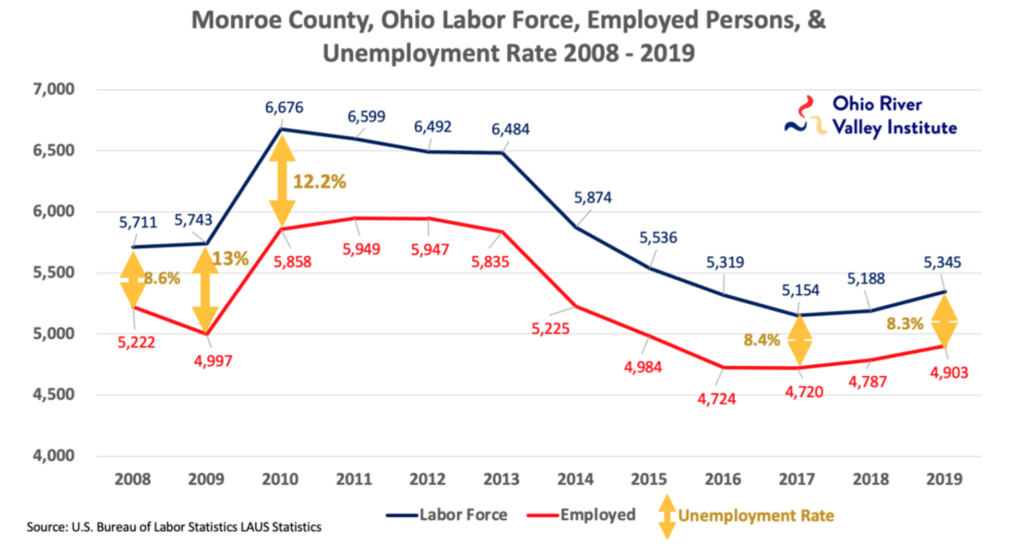

The two Ohio counties Chadsey mentioned reduced their unemployment rates by losing workers even faster than they lost jobs. Take a look.

The numerator — people with jobs — didn’t increase. The denominator — people in the labor force — got smaller. That’s a double whammy economically because, in addition to losing jobs, Belmont and Monroe counties’ talent pools were diminished as people either stopped looking for work or moved away altogether. And the loss of talented workers can have profoundly negative long-term consequences because a qualified labor force is often the first thing prospective employers look at when considering whether to locate or expand in a community.

How industry “investments” aren’t really investments in local counties

In the preceding clip, Chadsey also makes reference to “the $86 billion our members (meaning oil & gas exploration and production companies) have invested” in Ohio. The problem is that much of that “investment” is actually money that is spent elsewhere and never enters local economies in Ohio’s major gas-producing counties.

Many of the workers who drill fracking wells and much of the equipment, material, and supplies that are used in fracking as well as the service providers that support drilling and production, come from outside of the state — and often from well outside the region. Residents of the 22 major gas-producing counties are well familiar with the man camps that provide temporary housing for itinerant oil and gas workers and the pick-ups and heavy duty trucks carrying Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana license plates. Those places and others are where much of the investment Chadsey talks about actually went.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth doesn’t matter if peoples’ incomes don’t grow as well

Another of the industry’s favorite data points is the region’s astonishing growth in economic output as measured by Gross Domestic Product. As noted in the ORVI study, inflation-adjusted output in the 22 counties that constitute Frackalachia grew at a rate three times faster than that of the nation as a whole from 2008 to 2019. The problem is that Personal Income — the income received by local residents — did not grow in concert with GDP and in some cases not at all.

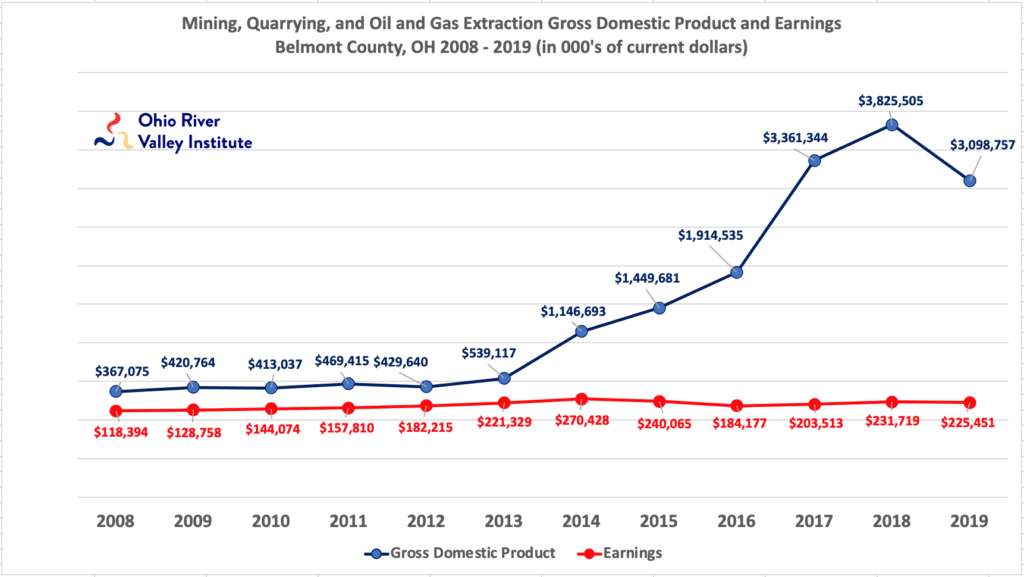

This is vividly illustrated by the following chart, which shows, in current dollars, changes in GDP and Earnings in the Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction sector in Belmont County, Ohio between 2008 and 2019. Earnings, which includes wages, salaries, and proprietors’ incomes, is a key component of Personal Income. While GDP for the sector skyrocketed, starting in 2014, Earnings didn’t budge.

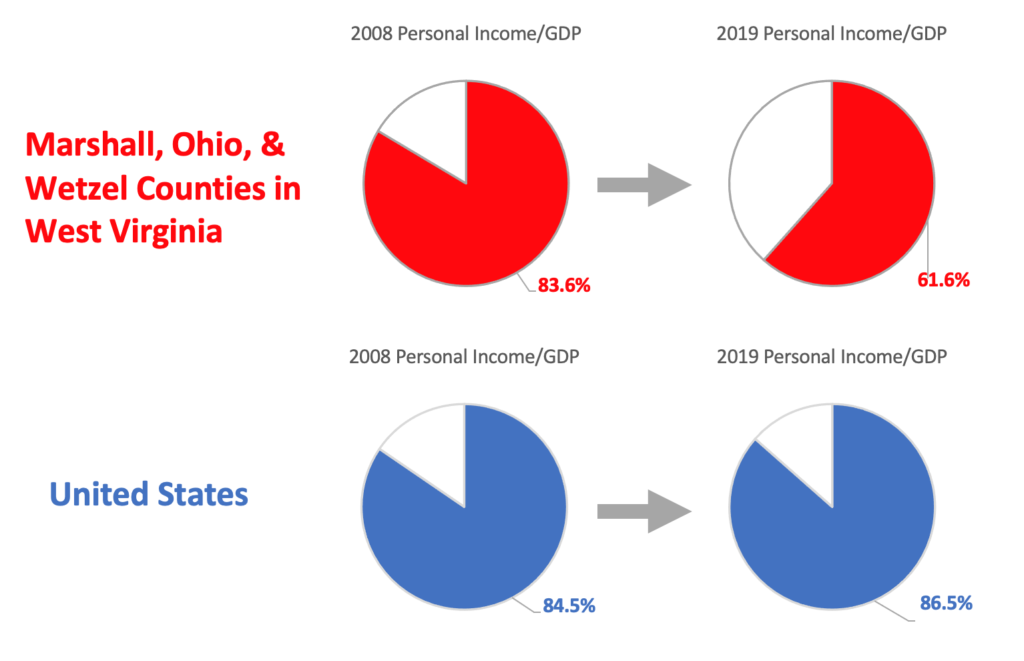

We see the same disturbing dynamic in the relationship between GDP and all forms of Personal Income, which includes income from royalties, investments, government transfer payments, and other sources in addition to Earnings. In 2008, the three West Virginia Frackalachian counties directly across the Ohio River from Belmont County — Marshall, Ohio, and Wetzel — realized about the same share of GDP as Personal Income as did the nation. But, when the natural gas boom came along, they suddenly saw their ratio of Personal Income (PI) to GDP plummet from the mid-80’s to the low 60’s.

The reason for the precipitous drop in the PI/GDP ratio in West Virginia’s Frackalachian counties is that only about 14% of the growth in GDP that was spurred by the fracking boom actually landed in the economies of those counties. The other 86% landed elsewhere. That is why industry citations of “economic growth” as an indicator of the boom’s contribution to prosperity should be dismissed out of hand.

Why royalty payments can be almost meaningless for local economies

To distract attention from the failure of the natural gas boom to produce job and income growth, industry defenders often try to shift attention to the royalty payments they say are making local property owners rich. Sometimes they do.

There are examples of landowners getting a windfall from leasing drilling rights. But that only helps the local economy as a whole if a substantial portion of that income is spent locally. And evidence suggests that relatively little is.

As far back as ten years ago, Bucknell University economist, Thomas Kinnaman, recognized that local spending might fall far short of expectations. In his critique of a frequently cited American Petroleum Institute economic impact study that claimed the fracking boom would generate 250,000 new jobs in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, Kinnaman identified a series of leakage points that siphon royalty revenues away from the region and local economies.

First, royalty payments are a function of the market price of natural gas, which has been only about half as high as the figures assumed at the beginning of the last decade when the most outlandish jobs predictions were being made. Second, many property owners who receive royalties are not local residents. They include both businesses and individuals who own property in the major gas-producing counties, but who are located elsewhere, often out of state. Third, royalty recipients who do live in the major gas-producing counties may save most of their proceeds rather than spend them locally or they may use the proceeds to pay down debts or make purchases outside the region.

Taken together, these factors mean that the portion of royalty payments that actually lands in local economies may be only a fraction of the amount delivered to recipients.

How data can be used to confuse rather than clarify

Perhaps the most bizarre form of statistical misdirection that greeted the ORVI report came from an organization called Pittsburgh Works Together (PWT), which criticized the report on the grounds that it should have used a different federal government source for jobs figures.

It should be pointed out that the source upon which the report is based — the federal government’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) — is also the source on which the federal government and all fifty state governments base their job counts.

Instead, PWT argued for the use of U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data, which also counts personal gigs like being a business proprietor, an Uber driver, or an Amway distributor — positions which do not provide benefits, are not covered by unemployment insurance. Those are worthy undertakings, however they are not jobs in the sense that, if the person doing them chooses to stop, there is no remaining position for someone else to fill. That is why, when the federal and state governments report jobs figures they do it based on QCEW data as did ORVI in its report.

The bizarre thing about PWT’s insistence on using BEA data is that the outcome for jobs isn’t significantly better than the QCEW-based outcome in ORVI’s report. PWT’s alternative data source puts the job growth figure for Frackalachia at just under 16,000, which is only slightly more than the 5,660 additional jobs found in the ORVI report. And both numbers pale in insignificance against the 450,000 regional jobs promised by industry-supported economic impact studies, a large portion of which should have but did not show up in the Frackalachian counties that produce over 90% of the region’s natural gas.