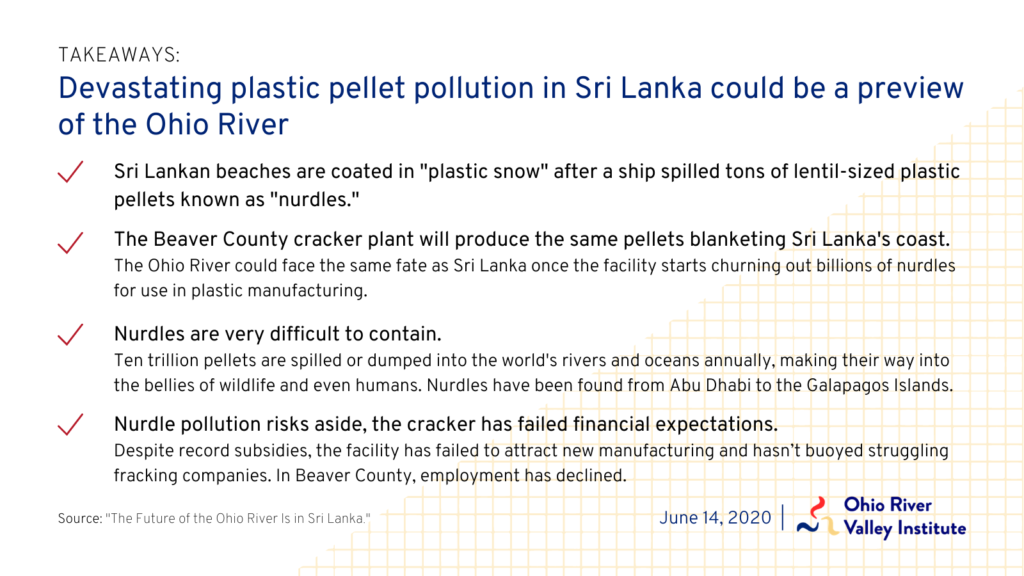

To see the future of the Ohio River you can look to a place that is almost its antipode: the tropical coastal waters of Sri Lanka. It’s there, some 9,000 miles away as the crow flies, that residents have recently discovered the scourge of pollution from the tiny resin pellets that are used to make plastic products.

On June 3, a cargo ship near the port city of Colombo suffered a chemical fire that crews were unable to extinguish. As the ship listed and sank toward the seabed, officials feared that it would spill even more of the chemicals and fuel oil onboard. Yet petroleum products may be the least of the pollution problems caused by the sinking. On its way down, the X-Press Pearl also spilled billions of tiny plastic pellets into the ocean that soon began washing up several inches thick on beaches and coastlines 75 miles away. Dead fish have already begun to wash ashore, raising alarms about the punishing effects of plastic pollution on all manner of marine life and threatening the country’s valuable tourism and fishing industries. Experts believe that ocean currents may yet carry the pellets as far away as India, Indonesia, and the east coast of Africa.

That fate, or some version of it, could very well be in store for the Ohio River once the controversial “cracker” plant in Beaver County, Pennsylvania starts operating. That facility is designed to produce exactly the same product: billions of tiny plastic pellets, sometimes called nurdles, that are used to manufacture all manner of plastic products, from shopping bags to drinking straws to bubble wrap. And despite assurances from Shell, the site’s owner, there is not much evidence that the pellets will stay where they are supposed to.

An example of the risk can be found much closer to home, on the Mississippi River. As recently as August 2020, residents downstream of New Orleans begin finding their shores coated with uncountable millions of nurdles that were swept away after a cargo container fell off a ship at port. The results, as documented by Desmog, amount to an ecological disaster. The pellets are bound to contaminate fish, birds and other wildlife that will mistake them for food. In fact, this is precisely what happens in Scotland, where locals find birds ingesting large quantities of the pellets in a nesting sanctuary near a cracker plant much like the one under construction in Pennsylvania.

The unfolding tragedy in Sri Lanka should not be a bit surprising. Designed for ease of transport and versatility in manufacturing, these tiny pellets are moved by ship and barge, truck and train. And they are escape artists: researchers estimate that each year approximately 230,000 tons of nurdles end up in the environment, accidentally spilled or otherwise released by the plastics industry. Given that a single nurdle weighs only about 20 milligrams, this means that more than 10 trillion tiny plastic pellets are entering the world’s rivers and oceans every year.

Some nurdle pollution results from shipping spills as happened in 2017, when a hurricane hit the Port of Durban in South Africa, causing two container ships to collide and sending 49 metric tons of nurdles into the ocean. The translucent beads quickly spread along more than 1,200 miles of coastline, with some landing on the beaches and some making it as far as Western Australia over the following year. Months after the spill, South African authorities had retrieved only about 23 percent of the spilled nurdles, with the rest likely never to be recovered.

Other times, nurdle pollution results from the manufacturing process. A peer-reviewed study on the southwest coast of Sweden found that a polyethylene producer in the industrial town of Stenungsund accidentally releases millions of pellets annually. It’s the same story in Scotland, where a large petrochemical manufacturing site outside Edinburgh yields a heavy concentration of nurdle pollution in the Firth of Forth, a nearby coastal estuary. So heavy is the nurdle pollution there that during a beach cleanup, volunteers collected more than 450,000 pellets in just over two hours.

More troubling, there is evidence that some plastics manufacturers may actually dump nurdles into the environment. In 2019, Formosa Plastics was forced to pay a $50 million settlement after losing a lawsuit alleging that the company had illegally dumped nurdles and other pollutants into Lavaca Bay in Texas.

Regardless of how they spill into the environment, nurdles seem to be everywhere. Citizen scientists have found nurdles in a depressing number of places: on beaches in Abu Dhabi, Ecuador, South Africa, and on and on. Even the world’s most protected sanctuaries are not immune: volunteers collected more than 1,000 nurdles on the Galapagos Islands in less than two hours in March 2019.

Once the Beaver County plant starts up, it is quite likely that the Ohio River—including places far downstream from Beaver—will soon see another wave of pollution in the form of tiny plastic pellets. Whether they escape from Shell’s new facility or from river-going barges or rail cars or some other way, it is likely these nurdles will make their way into the bellies of fish, birds, turtles, and other animals in the region. There is even evidence that plastic contamination could make its way up the food chain into the people who hunt and fish in the Ohio Valley.

It’s hard to see the upside for a project like the one under construction in Beaver now. Lavished with the biggest taxpayer subsidy in Pennsylvania’s history, the giant facility has yet to attract even a single new manufacturing plant to the region, contrary to the promises of boosters. It has not proved a boon for the struggling fracking companies that will supply the site with the ethane needed to make the pellets. Nor has it helped the region’s gas-rich counties, which have only fallen behind their neighbors economically during the era of fracking. Even in Beaver County itself where the project’s construction was supposed to bring a boom, employment actually declined.

The bill has not yet come due, but it will. And unfortunately, a portion of it will be paid by the Ohio River and its communities, where we will likely have to deal with a fate not unlike the coast of Sri Lanka.