The bill for the 150-year legacy of oil drilling in Appalachia is coming due. Yet, drilling still continues, adding to the region’s backlog of unplugged and polluting oil and gas wells. This is a huge problem for the region because unplugged wells have been linked to the contamination of groundwater supplies and soil, they leak hazardous volatile organic compounds into the air, and they leak climate change-accelerating methane.

ORVI’s latest report, Filling the Hole, estimates that there may be more than 1 million wells that need to be plugged in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. Safely decommissioning all these wells could well cost more than $100 billion, but existing policy has failed to make sure the industry pays, with only a tiny fraction of decommissioning costs set aside. Unless state leaders take action to ensure that the industry pays to clean up its mess, the astronomical cost of decommissioning these wells will fall almost entirely on Appalachia taxpayers. Or worse, few of the wells get plugged, which will compromise health, economic development, and our environment.

The report divides Appalachia’s oil wells into three categories: legacy wells, unplugged non-shale wells (mostly conventional), and shale wells (mostly unconventional) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conventional and unconventional wells schematic

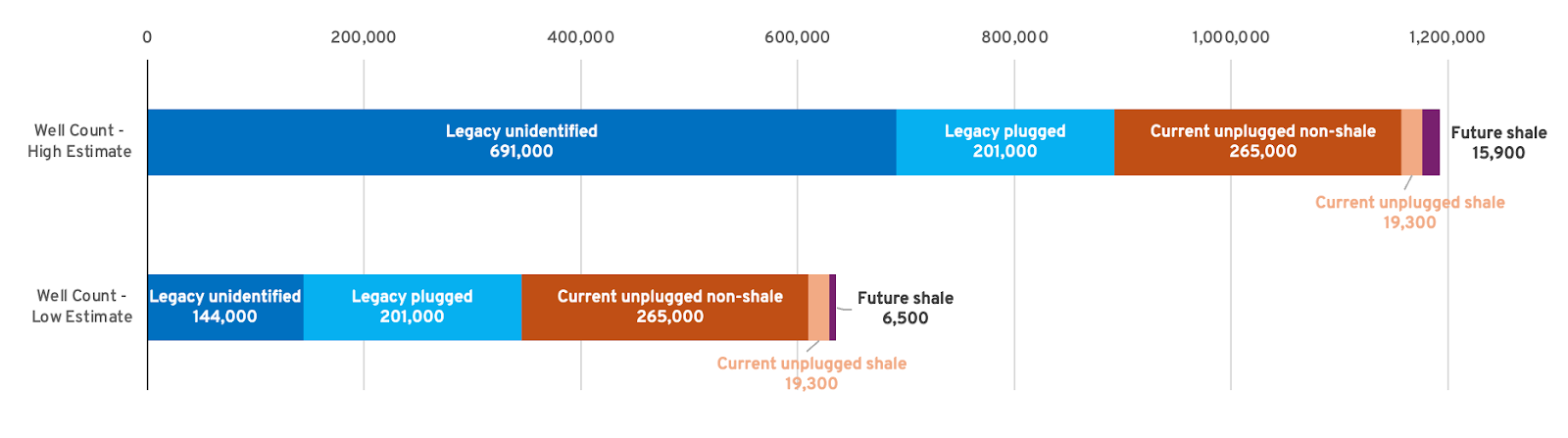

Legacy wells are historical conventional vertical wells. Some legacy wells have been plugged, but many plugs are old and leaky, and may need to be replugged to meet modern standards. The report estimates there are 201,000 known legacy wells that, if found to be leaking, will need to be replugged. In addition to the known legacy wells, the report estimates that there are between 144,000 and 691,000 legacy wells that are yet unidentified. The location of many of these wells has been lost over the decades.

Unplugged non-shale wells are wells that were drilled prior to the mid-2000s shale revolution and now produce little-to-no gas. These wells are mostly conventional vertical wells, but include some horizontal wells. The locations of all of these wells are known. The report estimates there are 265,000 unplugged non-shale wells in Appalachia.

Finally, shale wells are horizontal wells that currently account for the vast majority of Appalachia’s gas production. Compared to vertical wells, horizontal wells are much longer and far more productive. Since 2021, they make up more than 80% of new wells drilled in the US. The report estimates that there are currently 19,300 unplugged horizontal shale wells in Appalachia. Further, continued production in the Marcellus and Utica formations will result in between 6,500 and 15,900 more wells that will need to be plugged in the future.

In total, the report estimates there are between 600,000 and 1.2 million wells in Appalachia that need to be plugged or replugged.

Figure 2: There are between 600,000 and 1.2 million wells to be decommissioned in Appalachia

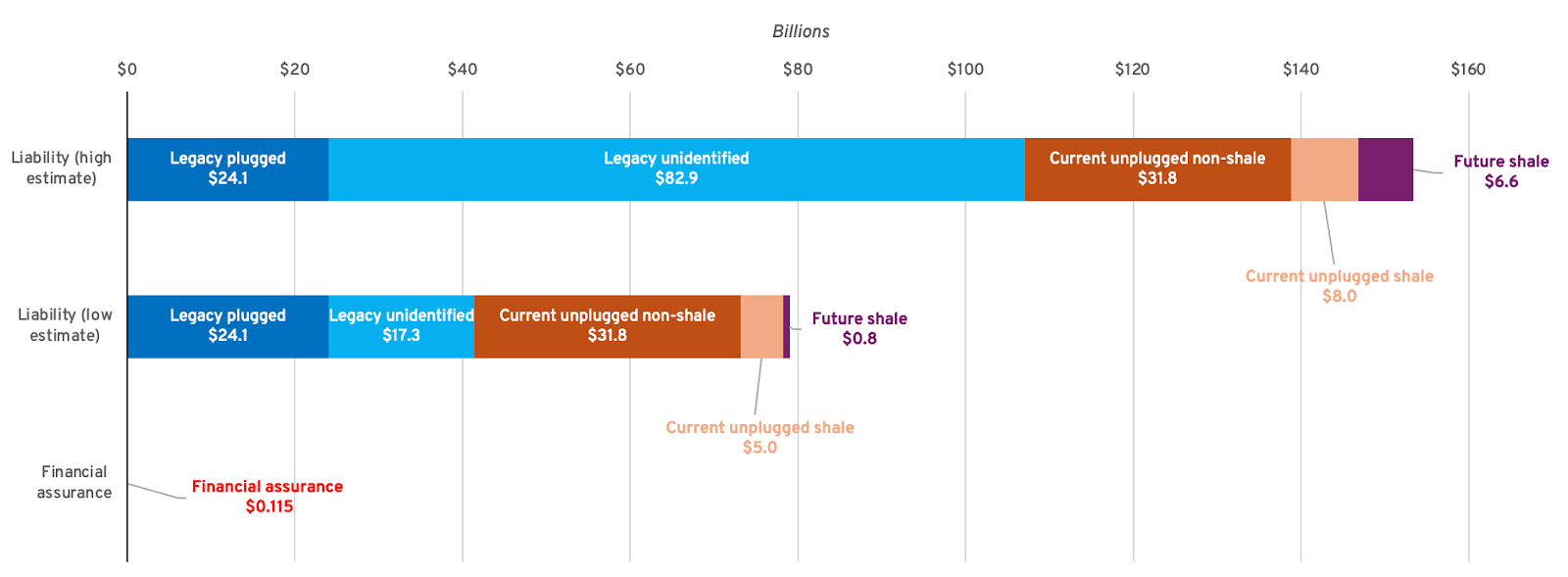

Plugging wells is expensive, and the industry has so far failed to provide adequate financial assurance for clean up. Financial assurance is a mechanism that requires owners and operators of polluting facilities to maintain resources to pay for the closure and cleanup of their facilities. The report finds that existing financial assurance for decommissioning oil wells across Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio amounts to $115 million. This is a paltry figure compared to the estimated $79 to $153 billion cost to plug all of Appalachia’s historical, current, and future wells. The sheer number of conventional wells means that they constitute the vast majority of Appalachia’s yet unpaid bill.

Figure 3: Decommissioning cost estimate

The estimated cost of decommissioning wells is dependent on a range of factors, like age, depth, and access to the well. And much like other sectors of the economy, costs have sharply risen over the last five years. For example, a 2021 report found that plugging conventional vertical wells costs at least $38,000 per well. However, ORVI’s newest report estimates the cost to be $120,000 per conventional well, on average, based on data from state-level plugging programs and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission.

At that cost, the report estimates the cost to replug the 201,000 legacy wells at $24 billion, though it is still unclear how many of those plugged wells will leak and need to be replugged. The cost to plug the unidentified legacy wells would be between $17 billion and $83 billion, depending on how many wells are identified. And the cost to plug current unplugged non-shale wells would be $32 billion.

Based on data in SEC filings by Appalachian gas companies, the report estimates the cost of plugging horizontal wells to be between $261,000 and $415,000. That means plugging the 19,300 already drilled horizontal wells will cost between $5 billion and $8 billion. And plugging the horizontal wells that will likely be drilled as the region continues producing gas will cost between $800 million and $6.6 billion.

In total, existing financial assurance amounts to less than 0.2% of even the low-end decommissioning cost estimate, which falls so far short of the decommissioning costs that it is hardly better than having no financial assurance at all.

Figure 4: Summary of well counts and decommissioning costs