In March, Senator Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) hosted the Secretaries of the Department of the Interior and the Department of Energy on a tour of West Virginia’s coalfields. After visiting a proposed steel mill in Mason County, they visited a center that educates the public about stream restoration and native wildlife.

West Virginia’s need for resources to address streams and mountains damaged by coal mining is extensive. In negotiations around the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law last year, Manchin—at the urging of local and national supporters that have advocated for mine remediation for years—succeeded in making sure that the Department of the Interior receives a historic boost in funding for the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) cleanup program.

On that tour, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland underlined her commitment to seeing that her agency’s new investments create “good-paying union jobs” across the region. But the agency has a long road ahead: the rural market for mine cleanup is weak and non-unionized. On its own, funding is unlikely to create union jobs; jobs will probably pay above the area average but below what can support a family’s needs.

In July, the Department of the Interior issued its final guidance on the AML funding in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and it includes policy tools that could over time transform the reclamation market. But it’s only a first step: implementation of the program happens at the state and tribal level, where agencies will now need to establish new policies and tighten enforcement.

Informed by listening sessions with labor unions in the region, Ohio River Valley Institute and partners offered multiple rounds of comments to the Department regarding the program, many of which are reflected in the guidance.

This post covers the main labor aspects of the final guidance and our suggested initial steps states and tribes can take to move toward securing a skilled, well-paying union workforce. Key takeaways include:

- For the first time, AML contracts will be subject to federal Davis-Bacon prevailing wage law. State enforcement will be key.

- Large reclamation projects are encouraged to be done by a union workforce—and agencies are urged to prioritize more large contracts and bundle small projects.

- Training programs can create a pipeline for reclamation work and provide on-ramps to the industry for locals with no construction experience. States should develop relationships with unions and contractors in their area to coordinate on apprenticeships.

- Coal sector workers will have a leg up in the hiring process.

- Irresponsible firms, like coal companies with violations, can’t bid on reclamation projects.

For the first time, AML contracts will be subject to federal prevailing wage law.

When the government funds a construction project, workers should be paid decent wages and benefits. That idea was made law nearly a century ago when Congress passed the Davis-Bacon Act, ensuring that workers on public construction projects are paid at least the wage and benefits currently “prevailing” for similar work in the local market. The law prevents low-road contractors from undercutting other firms by paying their workers poverty wages. In so doing, the Davis-Bacon Act both a) ensures better pay and benefits for workers and b) levels the playing field for contractors who are unionized.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law expands Davis-Bacon coverage to energy-related construction projects, including abandoned mine land reclamation. A local union leader in Kentucky described the requirement as nothing short of a “game changer.”

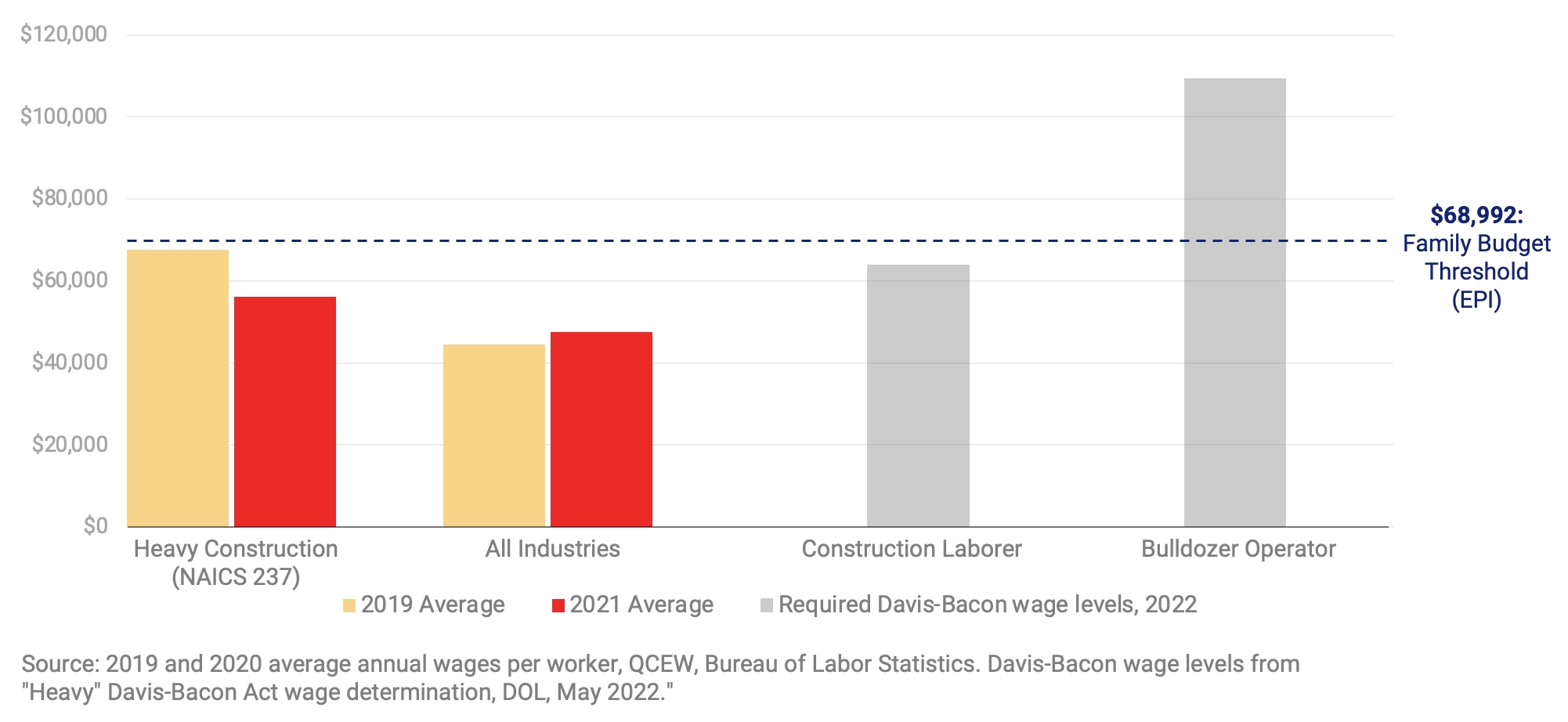

In Pike County, Kentucky, a full-time worker in the heavy construction sector earned around $56,000 on average in 2021, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. By contrast, Davis-Bacon required pay on heavy construction projects in Pike County is $64,000 for construction laborers and $110,000 for bulldozer operators (two common occupations on AML projects) working full-time.

Figure 1: Annual Wages per Worker, Pike County, KY

However, enforcement is half the battle. If low-road contractors know they can get away with illegally paying lower wages and benefits or diverting some of the money, union contractors will continue to struggle to win these contracts and workers will suffer. It will also mean less income flowing through local communities where workers live.

Recent research demonstrates payroll fraud in the construction industry is widespread (up to 20% of workers are illegally misclassified as independent contractors or paid ‘off the books’). It is not uncommon for firms to claim that they are providing the level of fringe benefits owed under prevailing wage laws while the actual level of those fringe benefits are lower—enabling them to cheat workers of benefits they are entitled to. (More examples in our comments to the Department of the Interior.)

The Department’s guidance directs states and tribes to insert Davis-Bacon clauses in all contracts and to withhold payment from contractors who violate the law. We’ve outlined basic steps agencies can take to tighten Davis-Bacon enforcement.

1. Actively monitor compliance by comparing payroll data from employers with interviews directly from workers, and audit contractors as necessary.

Active monitoring helps verify that workers know their rights, aren’t being lied to by their employer, and are being paid what the contractor is reporting. The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, for example, uses an active monitoring system that includes monthly surveys of workers on covered projects.

2. Publicize when there is a violation.

Recent research found that when the Occupational Safety and Health Administration published a press release of a health and safety violation it “led other facilities to substantially improve their compliance,” suggesting that if AML agencies routinely publicize Davis-Bacon violations it is likely to improve compliance across the program–not just among the firm in violation.

3. Train AML officials and inspectors on Davis-Bacon enforcement.

Historically, when agencies implement Davis-Bacon regulations for the first time, staff often lack experience in enforcement (i.e. how to handle reports of violations). States and tribes should take advantage of Davis-Bacon trainings offered by the Department of Labor, and the Department of the Interior should work with the Department of Labor to create an AML-specific training.

Large reclamation projects must be done by a union workforce—and agencies are encouraged to prioritize more large contracts.

In a huge victory for cleanup workers, the guidance requires that reclamation contracts over $1 million use a union workforce. If not, the state or tribe must explain how the project will provide a supply of skilled labor, wages, and benefits commensurate with necessary skills, local hires or other community benefits, a safe and healthy workplace that avoids delay, and minimized risk of labor disruptions. The guidance also encourages agencies to support fair labor practices and clarifies that funds cannot be used to oppose or support union organizing.

Union density in the reclamation sector is low. According to listening sessions with unions and contractors in the Ohio River Valley hosted by ReImagine Appalachia, few union contractors pursue reclamation contracts, in part because they are small: the median reclamation contract in Kentucky was $46,000 in 2020-21; in Pennsylvania it was $390,000 in 2019-21.

Unions improve pay, benefits, and provide safer working conditions. When union-density is high, those benefits spread to non-union workers, reducing economic inequality and gender and racial/ethnic wage gaps. Unions improve people’s health, civic participation, and provide other community benefits.

To move towards union contracts, states and tribes can take several steps:

1. Develop relationships with building trades labor organizations in their area and coordinate with them for large projects.

For projects over $1 million, the contractor can be union or use a Project Labor Agreement (PLA), which is an agreement with a union(s) regarding the terms and conditions of employment for a specific construction project. Union workforces and PLAs can provide significant benefits for agencies, including a dependable supply of skilled laborers, quality work, and on-time project delivery.

PLAs are the gold standard for union project delivery on public construction projects, and they’re common on reclamation projects in Illinois, for example, where state regulations require them. But PLAs are not the only way to use a union workforce on reclamation projects, and they may not be a realistic option for reclamation contracts in the political context of some states—at least not at first.

While the guidance directs agencies to use union firms on large projects, it does include an “escape valve” for agencies in cases where that may not be possible, then requiring agencies to explain how and why another workforce option will deliver similar results. Agencies can start this process by increasing awareness and coordination with unions and union contractors in AML areas.

2. Bundle contracts.

Historically, agencies have not pursued many projects over $1 million. The guidance encourages larger projects and the bundling of multiple small projects into larger contracts. Bundling can lower reclamation costs and time. It can also help attract bids from union firms, which tend to be bigger and pursue larger contracts.

States and tribes should take a hard look at projects previously out-of-reach because they were too expensive, like smoldering mine fires and coal refuse piles. Prioritizing these projects are a win-win that improve the environment for local residents and present a large project that could be attractive to a unionized workforce.

Bundling is a common practice among transportation agencies and is promoted by the US Department of Transportation. Bundling contracts to include multiple reclamation projects of the same problem type (AML problems are grouped by type, such as clogged streams and portals) in a similar geographic area could achieve cost and time savings.

The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation bundled the rebuilding, replacement, or removal of 67 county-owned structures in five geographic districts for $33 million, saving up to 50% on design and up to 15% on construction. By bundling two to three bridges per contract, the Ohio Department of Transportation was able to complete 210 bridges with a $110 million budget, 10 more bridges than expected (some cost savings may have been realized by bundling 100 or more of the bridges together for financing).

3. Establish a network to share data and best practices.

As states and tribes pursue bundling, they should rigorously track costs for various problem types and geographies and constantly update their bundling protocols based on those insights. Bundling in highway construction has shown, for example, that some types of projects show significantly more cost savings in bundling in others. To optimize savings, the Indiana Department of Transportation even uses an algorithm trained on historic data to select the best bundle of projects, considering geography, project type, and other factors.

Coal sector workers will have a leg up in the hiring process.

One goal of the bipartisan infrastructure law is to ensure that the benefits of cleanup are as accessible as possible to workers whose lives have been turned upside down by the collapse of the coal industry. The guidance clarifies—at the suggestion of Ohio River Valley Institute and others—that a broad interpretation of impacted workers will be used: all “current and former employees of the coal industry.” Eligible workers are not strictly miners, but states may want to further clarify if eligibility extends along the coal supply chain, such as to rail workers who hauled coal.

While the guidance does not require firms to hire a certain number of coal workers, it suggests agencies require firms “give preference” to coal workers in hiring for reclamation projects and report how many are employed. States and tribes will need to find a way to implement the provision alongside their procurement code, as well as in different geographies.

While coal workers are supposed to get a leg up in areas where there are many eligible candidates, the guidance makes clear that the provision does not apply to areas where eligible workers are unavailable—such as in places where the coal industry has long died out or where workers have moved down the road in search of work.

Training programs can create a pipeline for reclamation work.

Apprenticeships are training programs where participants are paid to learn a craft through a combination of work on real-world projects and classroom instruction. They work well for common crafts in mine reclamation, such as operating heavy machinery.

Apprenticeships pose two key benefits: providing a steady supply of skilled workers at a time of rapidly increasing demand for reclamation, and providing on-ramps to the reclamation industry for local residents with no construction experience, including historically disadvantaged groups.

Joint apprenticeship programs are jointly financed and managed by unions and contractors, and they are advantageous over other training programs in that they are directly linked to an employer (i.e., they are training programs tied to a job). If reclamation jobs are to be a pathway out of poverty in struggling coal regions, then accessible, paid training opportunities are a must. According to the Illinois Economic Policy Institute, “The annual income gain from participating in a registered apprenticeship program [in Illinois] is greater than the effect of having an associate’s degree, as well as many bachelor’s degrees.”

Public construction projects like reclamation can be addressed by formally linking apprenticeships to the public program, such as by requiring that a share of job hours on a project be completed by apprentices. The Interior Department doesn’t go this far, but it offers some initial steps. For one thing, requiring Davis-Bacon regulations on reclamation contracts will support apprenticeship programs, both because it a) levels the playing field for larger, more unionized firms that tend to invest more in apprenticeship training and b) firms are incentivized to include some apprentices on reclamation projects because starting apprentices earn less than 100% of the prevailing rates for experienced workers.

States and tribes should be proactive in coordinating with unions and contractors on apprenticeships

Agencies will need to be creative in developing ways to provide a steady supply of projects to contractors with joint apprenticeship programs. Reclamation contracts larger than $1 million must use a union workforce—presumably trained through apprenticeship programs—or must describe how a registered apprenticeship program or other avenue will deliver sufficiently skilled workers. Smaller AML contracts don’t have the same requirements, but the Department strongly encourages states to do outreach to labor organizations about training programs.

Irresponsible firms, like coal companies with violations, can’t bid on reclamation projects.

Increased AML funding risks attracting unscrupulous contractors who may rush to a new pot of money. The Department of the Interior maintains a database, the Applicant Violator System (AVS), to track the web of companies (and their subsidiaries) who violate coal mining permits. The U.S. General Services Administration maintains a separate database, the System for Award Management (SAM), used to track all contracts awarded by the federal government.

According to the guidance, firms are ineligible to bid on AML contracts anywhere if they have an outstanding coal mining permit violation in AVS or are suspended or debarred in the SAM system. These provisions aren’t new, but it is unclear how uniformly they have been enforced across the country.

The AVS system may become more relevant with the new hiring preference for coal workers—which some coal companies may use to bolster a move into the reclamation business. As coal dwindles, it is not hard to imagine operators trying to backfill lost revenue with reclamation contracts, especially as the scale of those contracts grows. For example, Arch Resources is the second largest coal operator in the US and a firm that highlights the “awards” of its reclamation subsidiaries, despite historic violations and a new lawsuit regarding pollution.

There are a few ways states and tribes can protect themselves from entering into contracts with irresponsible firms:

1. Set up procurement systems so firms are automatically verified through AVS and SAM systems.

2. Share information about contractors with the public and other AML agencies.

In 2021, the Pennsylvania Attorney General sentenced Glenn O. Hawbaker, Inc. for wage theft of $21 million in fringe benefits from its employees. That same year, Hawbaker Inc. was the apparent low bidder on the $2.2 million Baileys Trail System AML reclamation project across the state line in Ohio.

Sharing this information will protect agencies from penning contracts with bad actors. AML agencies of the Ohio Valley states could enter into a formal agreement to share information about irresponsible contractors operating regionally, and states could adopt stricter criteria barring irresponsible contractors from bidding.

The guidance is an excellent step in turning the tide toward “good-paying union jobs.” The Department will need to stand up new monitoring programs, use its convening power often, and hire a lot of new staff. But state and tribal enforcement—especially of the Davis-Bacon Act and union contracts—is where the rubber meets the road.

Most reclamation work in Illinois is done by union workers paid good wages. That’s not the case across the rest of the country, and it won’t be unless agencies take significant measures to change it. It’s no guarantee, but these policies provide a framework for states and tribes to get there over time.