“After decades of delay and decline, America’s workers stand ready to rebuild our country.”

That’s what AFL-CIO President Liz Shuler said about the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law as she joined President Joe Biden in the Rose Garden. At the signing ceremony, the President underlined how workers would now have the chance to take advantage of historic investments in trains, roads, and water lines. But for communities where resource extraction has occurred, an aspect of the law that didn’t get much fan-fare could have an even greater impact. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law invests $16 billion in cleaning up lingering damage from the coal and gas industries–environmental scars that are concentrated in Appalachia.

It’s been impossible to watch the president’s remarks after passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and miss that he wants to create “good-paying, union jobs” with the new money. Doing that for billion-dollar transit projects in metropolitan areas will be hard enough. Creating “good-paying, union jobs” in rural areas and in a fossil fuel remediation industry that is barely unionized is an even taller order. But it’s a problem we know how to solve–if President Biden and governors in Appalachian states are as serious about fighting for workers with their policy as they are with their words.

Without policy action, the mine reclamation market is unlikely to create union jobs. Union-density is too low, the labor market too loose, and collective bargaining law too biased toward employers. Mine reclamation jobs in the construction sector will probably provide pay above the area average but below what is needed to support a family’s needs.

All hope is not lost, though. Here I explore policies that could help increase pay and unionization in the reclamation sector if pursued by state and tribal reclamation agencies.

Repairing the damage will create jobs in struggling economies

The environmental and public health benefits of the coal mine and gas well cleanup provisions in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law are long overdue. They will make areas safer for nearby residents and for people far downstream–by decreasing risk of landslides and flooding, and neutralizing water pollution–and will reduce methane leaking from mines and wells. Reforestation will sequester carbon and increase native wildlife habitat and biodiversity.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law investments will create thousands of jobs reclaiming damage from mining–4,000 jobs, by my estimate. Counties with mining damage have an unemployment rate and poverty rate higher than the nation overall. While coal was blasted and shipped out of Appalachian towns, jobs repairing the damage from that blasting can’t be shipped anywhere. The cleanup program will mostly generate jobs in these struggling economies, so by its nature this investment could serve as an economic development boost.

But it’ll only be a boost to the degree that jobs actually improve people’s ability to sustain themselves. The big question is: will these jobs be any better than the precarious low-wage jobs that proliferate in the region?

Will reclamation jobs be union?

The construction sector might not be what first comes to mind when you think of fossil fuel cleanup, but that’s where most coal and gas cleanup jobs will be created. State agencies engineer plans for new reclamation projects and then procure a construction contractor to execute it. Jobs at those construction contractors require tasks like manual labor, operating small and heavy equipment, and in some cases specialized reclamation techniques.

Contractors who have won reclamation contracts in recent years have been virtually all non-union– that’s according to conversations Ohio River Valley Institute has had with labor organizations in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and West Virginia. Only a handful of projects in Appalachia in the past three years have been completed by union firms–and none in states like Kentucky. Why?

Historically, mine reclamation projects have not required prevailing wage rates for workers, which creates an uneven playing field for non-union contractors, who tend to pay their workers less and then undercut union contractors with lower bids. Union contractors may be able to complete the project more quickly and deliver higher quality work by a more skilled workforce, but state procurement codes often bypass these factors and go with the cheapest option, full-stop. Another difficulty is that union firms these days tend to be bigger relative to construction firms on average and mine reclamation contracts tend to be relatively small, making them unattractive for many union construction shops in the region.

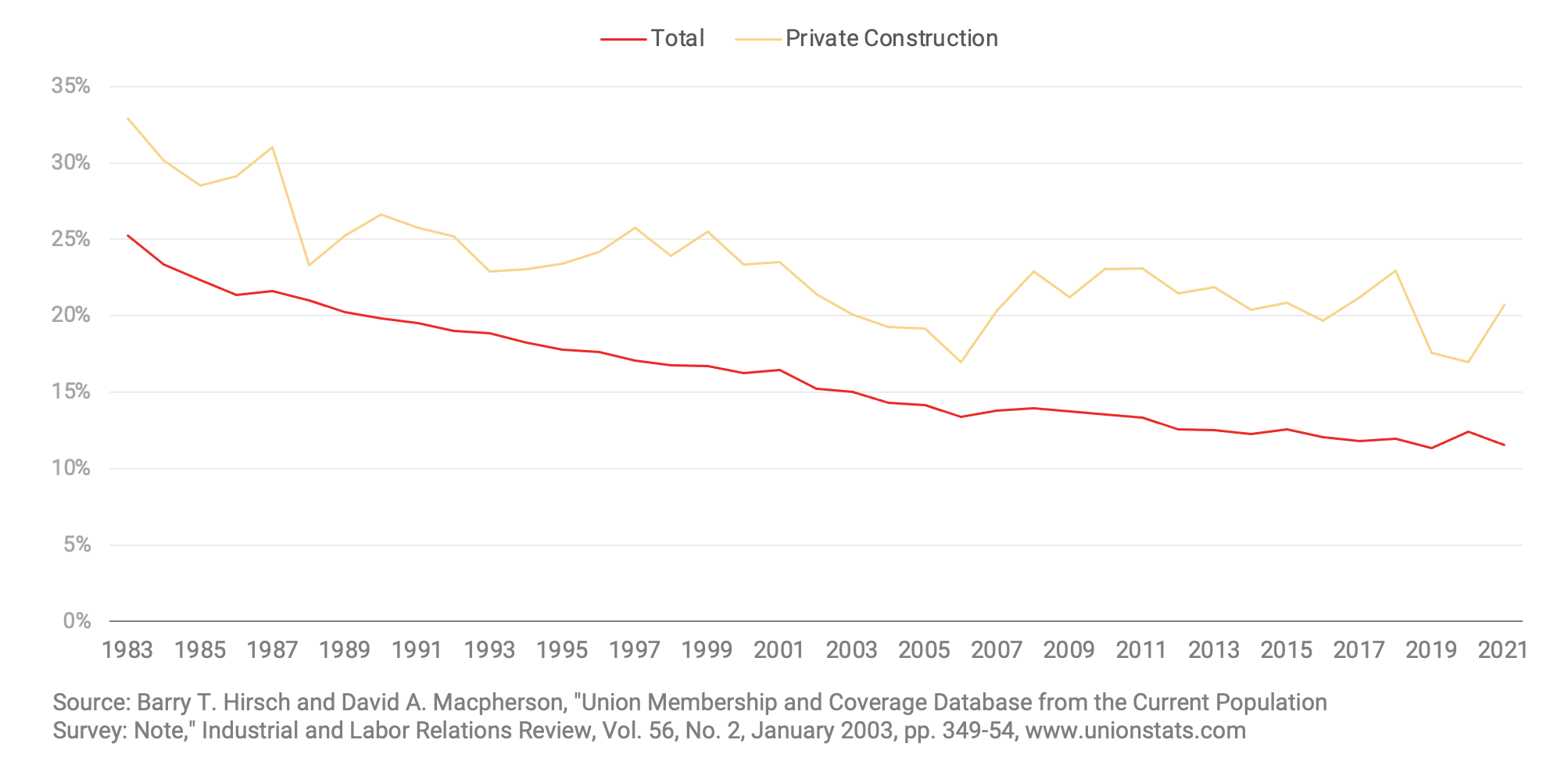

The low unionization rate in the mine cleanup sector is also a function of trends in the broader economy. In 1973, union membership in the US construction industry was 39.5%. After decades of deindustrialization, crushing unions, and gutting worker rights, that rate has been slashed to around 13%. The national trend is mirrored in states like Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia, where union density in construction has been cut in half from 30% to 15% since 1983. [There are a few exceptions, such as in Illinois and Pennsylvania, where state policies have helped keep construction union density higher.] The onslaught on worker rights hit the latest inflection point in the mid-2010s, when states like Kentucky and West Virginia passed so-called “Right to Work” laws and repealed long-standing laws that provided prevailing wages on state-funded public construction projects.

Figure 1: Union Membership (%), Private Construction

Hover over chart to view data.

Rural areas where abandoned mines are located likely have even lower union density than the state averages shown above. Rural Appalachian counties have historically higher unemployment rates, and fewer job options creates a dynamic where workers have relatively less bargaining power.

Will remediation jobs be good-paying?

In Appalachia–as defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission–pay in the construction industry is higher than the economy overall. In 2017 average earnings per worker were 15% higher in the construction industry than across all industries ($53,773 for NAICS 23, compared to $46,697 for all industries). Construction jobs also paid about 10% more than the coal, gas, and other mining industry in 2017 at a regional level ($53,773 earned on average in NAICS 23, compared to $48,996 in NAICS 21).

Though union density in construction is not what it was once, the above-average pay in construction is explained in part by both that long history of unionization and the fact that the construction industry remains more unionized than the economy overall. As recently as the early 1980s, one-third of private construction workers in the Ohio River Valley–Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania–were union members. Over the period of 1983 to 2021, the union membership rate in construction was 7 percentage points higher than the economy overall, on average.

Figure 2: Union Membership (%), Ohio River Valley States

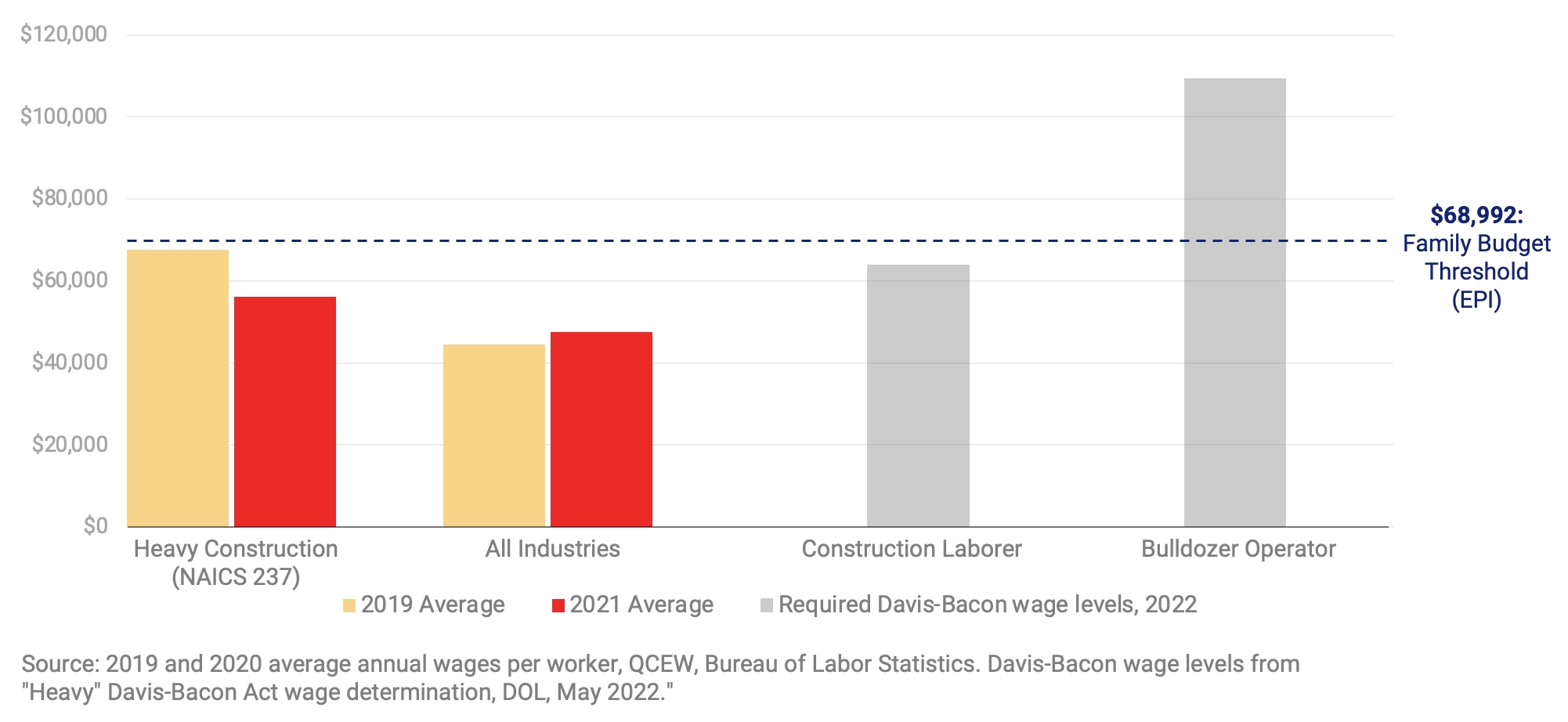

Is a construction job in rural Appalachia enough to support a family on? According to the EPI Family Budget Calculator, in Pike County, Kentucky, basic necessities for a family of four—housing, food, child care, health care, and some other expenses–cost $68,992 on average in 2020 (the most recent year for which price data is available for some expenses).

Figure 3: Annual Wages per Worker, Pike County, KY

Heavy construction is the construction subsector that includes the cleanup of mining damage and gas wells. Average annual wages per worker in heavy construction were 18% higher than the average across all industries in Pike County in 2021. Pay in heavy construction was even higher before taking a hit during the pandemic: in 2019, heavy construction workers made 52% more than workers on average across the economy in Pike County.

If you’re the sole breadwinner for your family of four, then a heavy construction job in Pike County probably wouldn’t quite pay for all of your necessities in 2021, though family circumstances can vary. This doesn’t include any money for leisure or travel for pleasure.

So, left to its own devices and without further policy action, the reclamation sector won’t be creating union jobs in Appalachia, and if Pike County is representative of the region then the jobs will be “good-paying” relative to the average job in the area but they won’t be enough to support a family on.

The good news is that we have a set of policies that can help address these issues, which I explore here. General policies like the PRO Act and AML-specific measures could make a big difference. The top of that list should be enforcement of Davis-Bacon prevailing wage regulations on reclamation contracts. Ensuring that reclamation contractors pay Davis-Bacon required wage levels in Pike County, for example, would ensure higher wage levels of $64,000 for construction laborers and $110,000 for bulldozer operators working full-time on those projects–jobs that would be “good-paying” for the area by nearly any standard.