In November 2021, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which made historic investments in the reclamation of land and water damaged by the coal industry before 1977. We have found that while the bill will only address about half of the remaining damage across the country, the investments are the largest in the program’s history and a categorical step forward in remediating the polluted water, dangerous mudslides, coal mine fires, piles of waste coal, and other problems from historic mining.

The Department of Interior announced the distribution of grants to states and tribes under the new program in February 2022. ORVI has compared those distributions with our estimates of the size of the problem in each state and tribal nation. While the distribution is an improvement over the formula historically used for AML grants, it is uneven in the sense that the IIJA money will get some states and tribal nations much closer to addressing all of the damage in their borders than others. ORVI estimates that the investments will support or create more than 4,000 jobs doing reclamation and thousands more jobs throughout the economy. In a future post, ORVI will explore AML reclamation job quality and labor standards, which vary by state and will be impacted by how the program is implemented by government agencies.

Below, we provide background on the bill, explain how the new investments compare to the damage that needs to be cleaned up, and offer estimates of jobs that will be created to do the cleanup.

What’s in the bill?

The IIJA has two main provisions relevant to the cleanup of Abandoned Mine Lands (AMLs). First, the IIJA will continue, for 13 more years, funding for AML cleanup first established by SMCRA in 1977 (“standard AML grants”). These grants are financed by a fee on coal production, which the IIJA extends—albeit at a 20% reduced rate—for those 13 years. Second, the IIJA creates a new funding stream for AML cleanup financed by the General Treasury (“IIJA AML grants”). It will appropriate $11.3 billion and distribute it to states and tribes equally over 15 years. On the whole, the grant programs are very similar: both funding streams provide funds to states and tribes to reclaim coal AML problems.

A section-by-section summary of the mine cleanup portion of the IIJA can be found here.

ORVI and partners provide recommendations for how to best implement this new program in a separate post here.

How do the new reclamation investments compare to the existing AML program?

The IIJA AML grants are similar to standard AML grants, but they do differ in some ways. The interactive table below compares these two AML grant programs, as well as the AML Economic Revitalization (AMLER) grants.

In contrast to the AMLER grants and the proposed RECLAIM Act, the IIJA AML grants (like the standard AML grants) do not require projects to have a formal economic development component. The IIJA AML grants require prevailing wages (i.e. Davis-Bacon wages); although the Trump administration did not require Davis-Bacon wages for standard AML grants, the Biden administration is currently reviewing the applicability of Davis-Bacon wage regulations to all AML grants.

The IIJA includes $25 million to update the AML inventory, and it may have different regulations around using funds for AMD set-aside programs. We examine those parts of the law in this post.

The IIJA includes labor standards related to prioritizing coal workers, a preference for aggregating smaller projects into a single large contract, and prevailing wages.

What’s the story behind mine cleanup making it into the bipartisan infrastructure law?

The fight to clean up the coal industry’s legacy of damage stretches back to the mid twentieth century, when Appalachians first organized against strip mining. The passage of SMCRA in 1977 created the federal Abandoned Mine Land (AML) reclamation program and instituted a fee on coal production to finance the program. Many of the groups behind the AML fee continued their efforts beyond the 1970s, urging Congress to extend the fee when it was set to expire in the 1990s and 2000s.

The modern movement around mine cleanup emerged about a decade ago. In addition to the historic focus on the environmental and public health need for cleanup, this new movement emphasizes the economic benefits of reclamation. As the idea of “green jobs” gained purchase in the early Obama years, people began to return to the AML program as not only a source of cleanup but as a model for a new economy in the coalfields—one that could create jobs cleaning up pollution.

In 2013, the modern AML movement began to take shape. Appalachia experienced a precipitous drop in coal mining in 2012, and in this context of uncertainty more people began to consider the advantages of AML cleanup. For the first time advocates began to propose not simply the extension of the AML fee but the addition of new investment. In 2013 Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC) and The Alliance for Appalachia (“The Alliance”) each hosted meetings in Central Appalachia where participants identified more federal investment in AML reclamation as a key priority for building an economic transition in the coalfields.

Spurred by the Highlander Center, Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center (ACLC) and The Alliance partnered on a participatory research project that led to a 2015 report I co-authored on the AML program. Out of this research project, ACLC, The Alliance, and Alliance member groups like Appalachian Voices founded a coalition around AML cleanup in 2015. The network, later deemed the “RECLAIM Coalition,” coalesced around an Obama Administration initiative that proposed using $1 billion from the existing AML Fund to accelerate investment in coal mine cleanup and tie it with development projects on reclaimed sites.

The coalition led an effort to demonstrate local support for the proposal, and in 2015 twenty-nine local governments across Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, and Tennessee passed resolutions urging Congress to take action on the proposal. The proposal was introduced in Congress as the RECLAIM Act in 2016, and the coalition grew to more than eighty organizations including local groups like Statewide Organizing for Community eMpowerment (SOCM), Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards (SAMS), Prairie Rivers Network, Eastern Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation (EPCAMR), Western Colorado Alliance, Center for Coalfield Justice, West Virginia Rivers Coalition, and Western Organization of Resource Councils (WORC); and national groups like BlueGreen Alliance, National Wildlife Federation (NWF), and Sierra Club.

In 2018 Appalachian communities doubled down on their support for the proposal when twenty-seven more resolutions were passed by local governments in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee, urging Congress to pass the RECLAIM Act. Due in large part to the wave of local action, the bill enjoyed strong bipartisan support in Congress. Rep. Cartwright (D-PA) and Rep. Rogers (R-KY) led the effort in the House, where the bill garnered 65 cosponsors in the 116th Congress. Senator Manchin became a leader on the bill in the senate. The RECLAIM Act did not pass, but it laid the groundwork for something even bigger: By the end of the 116th Congress, Senator Booker and then-Representative Haaland had introduced a bill to invest $10 billion in AML cleanup.

ORVI released research on the true cost of AMLs and a report on AML cleanup in early 2021, calling on Congress to appropriate $13 billion in AML cleanup over 10 years. Groups leading the movement for years similarly called for billions in AML investment in the infrastructure bill, and President Biden introduced a $16 billion proposal to fund AML cleanup and orphaned well remediation.

In June 2021, Senator Booker, alongside Representative McEachin, re-introduced his bill that included a $10 billion investment in AML cleanup. Manchin then introduced an energy infrastructure package that would appropriate $11.3 billion in AML cleanup over 15 years. During a congressional hearing on the bill, the Senator cited the ORVI report in part to justify the need for such a large appropriation for AML cleanup. The constellation of groups behind the RECLAIM Act continued to work with Congress throughout 2021 on the AML portions of IIJA.

Senator Manchin and Senator Barasso, the Ranking Republican on the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, came to a compromise in July that cut AML fees by 20% and extended them for only 13 years, which will cost an estimated $460 million in AML fees relative to Senator Manchin and Rep. Cartwright’s straightforward 15-year extension. The compromise also made states like Wyoming eligible for some of the new $11.3 billion. The final language in the IIJA is identical to this compromise language. (Despite the concessions to Senator Barasso, he still voted against the energy package that included the AML language and later voted against the IIJA.)

Over many years, the movement behind RECLAIM had established a strong bipartisan coalition for increased investments in AML, and in late 2021 was finally able to secure the AML provisions in the IIJA—an investment in AML cleanup that is 12 times the funding level of the RECLAIM Act. In addition, such a large victory no doubt came in part by having Senator Manchin, who hails from the state with the second largest AML problems and who had become a champion of the RECLAIM Act, as the chair of the committee with relevant jurisdiction, and by having a President in the White House that had prioritized mine cleanup during his first months in office.

The effort also likely benefited from the urgency that surrounded the AML fees—which were set to expire in September 2021—running parallel to when Congress was also considering large-scale infrastructure investment.

Will this new investment solve the country’s abandoned mine problem?

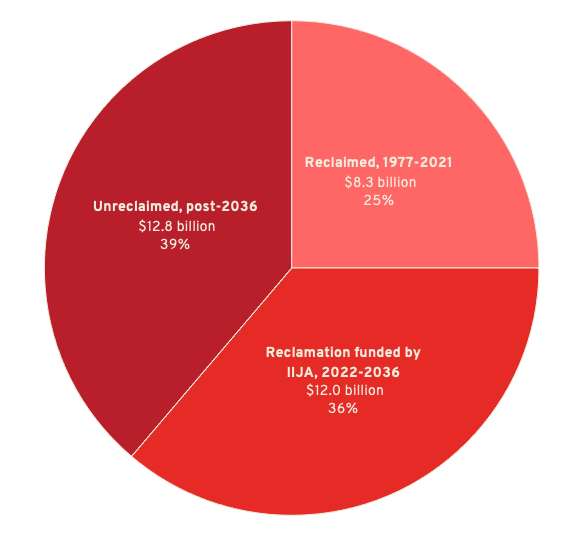

The IIJA represents the largest investment in mine cleanup ever—more than when the program was created in 1977. The AML program will remediate more damage in the next 15 years ($12 billion) than it has over the past 44 years combined ($8.3 billion).[1] The IIJA is increasing the annual rate of AML cleanup by almost 4.2 times relative to the average from 1977-2021.[2]

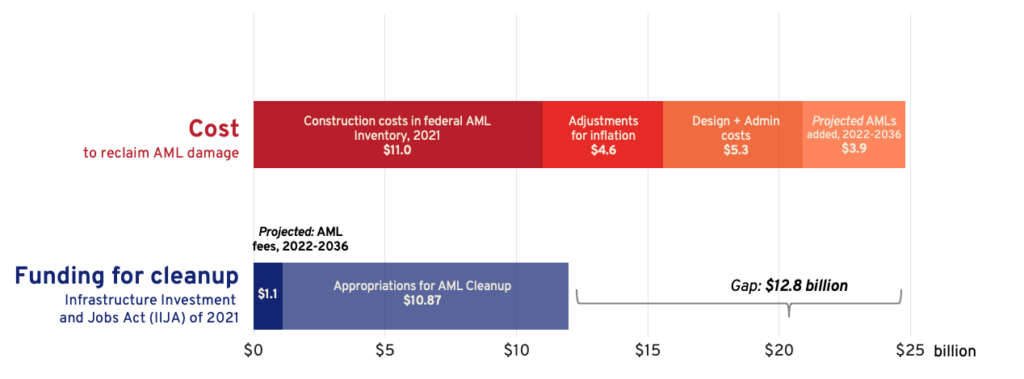

Figure 2. Funding for AML reclamation compared with outstanding damage [3]

Figure 3. Breakdown of total AML reclamation cost, by reclamation status

Projected AML cleanup of $11.95 billion includes the $11.3 billion appropriation in the IIJA for AML cleanup plus a projected $1.1 billion in AML fee collections; it subtracts $25 million for inventory updates as specified by the IIJA and 3.5% ($395 million) for federal administration costs.

This historic investment, however, will likely only address half of the approximately $25 billion in remaining damage from AMLs, leaving an estimated $12.8 billion in AML damage unreclaimed once the IIJA AML funds expire in 2037.

This $25 billion estimate includes the construction costs in the official AML inventory plus the estimates for updating old construction costs for inflation, estimated costs of designing reclamation projects and administering them based on historic data, and projected AMLs that will be discovered and added to the inventory over the next 15 years. The estimates are based on our 2021 report on AMLs.

Though ORVI advocated for funding at the level of $13 billion over 10 years, the $11.3 billion over 15 years in the IIJA does have its advantages. It represents a categorical step up in funding, and because the IIJA did not have to go through reconciliation, the drafters of the bill could extend the appropriation of AML funds beyond the 10-year limit imposed by the reconciliation process. The certainty of 15 years of funding allows federal and especially state AML agencies the stability to think more long-term—and more effectively—in their planning and hiring.

How many jobs will the IIJA create?

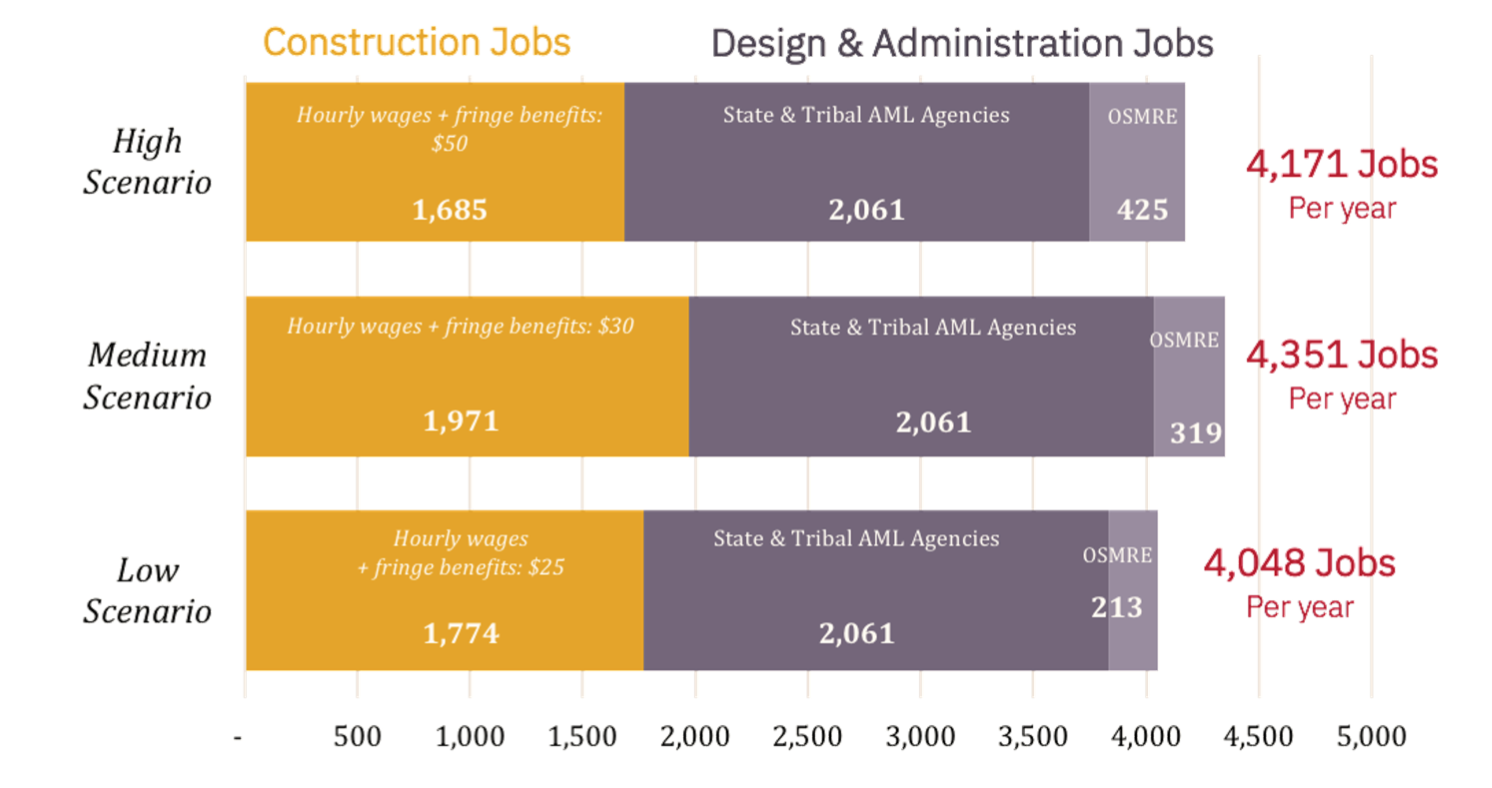

The AML section of the IIJA will create around 4,000 direct jobs per year for 15 years, by ORVI estimates. The figure below provides direct jobs estimates under three different sets of assumptions, low, medium, and high.

Figure 4. Estimated direct jobs created/supported by $11.95 billion IIJA AML investments, 2022-2036 [4]

AML cleanup requires three broad types of jobs: construction jobs at firms executing the reclamation plans, design and administration jobs at state/tribal agencies designing the reclamation plans, and jobs at OSMRE doing a variety of administration-related tasks.

The IIJA is estimated to create between 1,600 and 1,900 construction jobs per year for 15 years. The range of estimates assume $25 (low), $30 (medium), and $50 (high) in average gross hourly pay, assumptions which are based on relevant occupation data in AML states (see Dixon (2021)). The scenarios also assume payroll is 15% (low), 20% (medium), and 30% (high) of construction costs; the high scenario also assumes a 5% wage-push construction cost increase, which is why the high scenario estimates are lower than the medium.

Based on historic data on the AML program, the IIJA is estimated to create around 2,000 jobs per year for 15 years at state and tribal AML agencies and between 200 and 400 jobs per year for 15 years at OSMRE.

In addition to direct jobs doing reclamation, more cleanup will support jobs along the AML value chain. Spending on heavy machinery necessary for reclamation will likely rise—and jobs needed to manufacture heavy machinery along with it. A similar impact can be expected with other inputs, such as seeds, saplings, fertilizer, fuel, and gravel. These effects are estimated to create/support 2,310 indirect jobs per year for 15 years, based on IMPLAN U.S. input/output tables in Pollin et al. (2021).[5] More spending should also circulate in regional economies, as workers spend their wages on goods and services in surrounding communities. This will create/support an estimated 3,982 induced jobs per year for 15 years.

By these estimates, the IIJA is estimated to create/support more than 10,000 total jobs per year for 2022-2036 (around 4,000 direct jobs plus over 6,000 indirect and induced jobs). [These estimates give us a ballpark idea of the jobs that’ll be supported by the program, but we should use estimates like these–which are based on many factors that can shift over the 15 year period–cautiously.]

In a future post I will explore questions of pay and unionization of AML jobs. In the meantime, see my comparison of likely wages of AML construction workers with poverty and living wage thresholds.

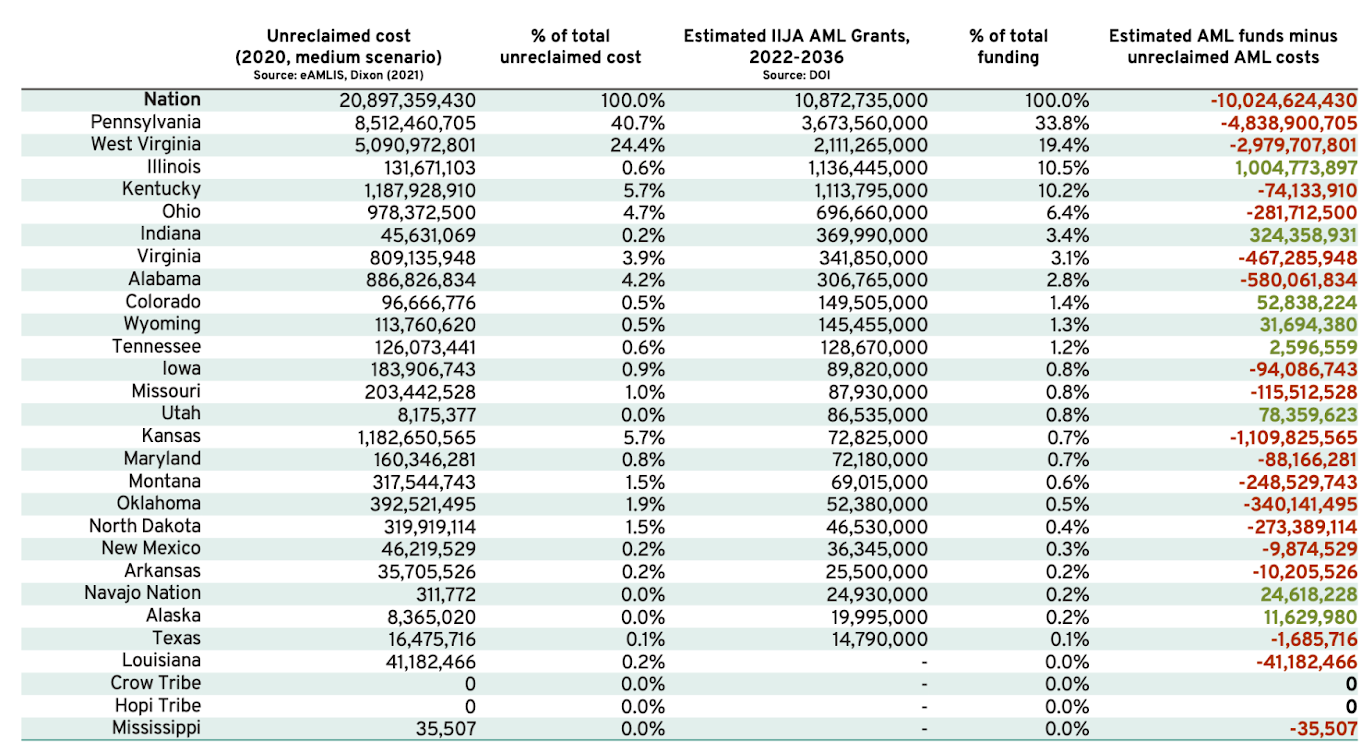

How do grant distributions to states and tribes compare to their outstanding damage?

In February 2022, the Department of Interior (DOI) announced the distributions of IIJA AML grants to states and tribes. These distributions will be delivered equally over 15 years, though there are potential exceptions which are explored here and which the grants announcement acknowledges. The figure below compares ORVI estimates of outstanding reclamation costs with the estimated total of IIJA AML grants (over 15 years) for each state/tribe.

Figure 5. Unreclaimed AML damage compared with IIJA AML grants [6]

Per the bill language, IIJA AML grants will be distributed to states and tribes according to how much coal was produced in that state or tribe prior to 1977. The idea behind this formula is that historic coal production is a proxy for unreclaimed AML damage. The formula is problematic. A superior approach would have been to update the AML inventory so that we have a reliable sense of how AML damage is distributed across the country and then use that distribution as a basis for the formula.

Using the inventory as a basis for funding distributions is not a far-off idea: it’s already done with AMLER grants (states with the “greatest amount of unfunded need” qualify for funding). The Booker-McEachin bill would have distributed AML funds according to “the proportion of unreclaimed lands and water.” Building on that language, Manchin’s original proposal last summer distributed funds on the basis of “the proportion of unreclaimed eligible land and water,” but this language was changed in the later version that eventually made it in the IIJA.

The funding formula in IIJA has a few shortcomings. The first is that some states and tribes have much more outstanding AML damage than others and the IIJA does not deliver money relative to a state or tribe’s need. For example, Maryland and Kansas will each receive about $70 million in IIJA AML grants, but Kansas has $1 billion more in unreclaimed AML problems than Maryland. Both states will see an uptick in mine cleanup, but for Kansas this uptick is a small fraction compared to its overall need. Distributing IIJA funds according to AML damage in the inventory would have addressed this problem.

The second downside is that some states could potentially get more AML funds than they need—though I think this is unlikely to happen. The figure above compares a state/tribe’s outstanding AML damage (as of 2020) with its IIJA AML grants. According to these estimates most states have more AML problems than they will be able to clean up with IIJA funds. And at first glance, the figure above suggests that a few states and tribes are unlikely to be able to spend all of their IIJA funds. But these calculations are based on the remaining AML damage in the inventory as of 2020.

AMLs are constantly being discovered and added to the inventory, and with this increased funding states and tribes are likely to add significant updates to their inventories of outstanding reclamation over the next 15 years. For example, states and tribes added about $500 million in outstanding AML damage to the inventory in 2021 alone. According to this table, only 4 states (Illinois, Indiana, Utah, and Colorado) have greater than $50 million in “excess” IIJA funds. Even in these cases, it’s likely that before the 15-year window for these grants is up states will find AML problems to remediate with these funds. (I have not included standard AML grants in these calculations for 2022-2036. These grants will supplement the IIJA funds, though I think they are unlikely to be large enough to alter the broad pattern discussed here.)

A third—and perhaps deeper—weakness of the formula is related to certified states and discussed here alongside recommendations for how to improve implementation of the program. While the formula is an improvement relative to the standard AML grant formula and ensures some funds for all eligible states and tribes, its downside is that it still does not distribute funds according to demonstrated coal AML need. Despite that downside, the large uptick in funding is welcome and on the whole significant investments are going to most states that have huge backlogs.

Endnotes

[1] According to Dixon (2021), an estimated $7.88 billion in AML damage had been reclaimed, as of October 2020. This estimate is updated for inflation (2020$) and also includes estimated design and administrative (not just construction) costs. Between October 2020 and January 2022, $277 million in completed AML construction costs were added to the AML inventory. Multiplying this figure by 1.34 for estimated design and administration costs and adding it the $7.88 billion estimate yields an estimated reclamation total of $8.25 billion through 2021. See below footnote regarding the estimate of unreclaimed AML damage.

[2] The estimated annual rate of AML cleanup for 1977-2021 was $187 million per year on average ($8.25 billion in reclamation divided by 44 years). The annual rate of AML cleanup for 2022-2036 is projected to be $796 million per year on average ($11.95 billion in reclamation from projected fees and IIJA AML grants divided by 15 years).

[3] The estimates are in 2020$. According to Dixon (2021), the total cost of unreclaimed AML damage as of 2036 is an estimated $24.85, which includes $11 billion in construction costs from the AML inventory (October 2020), $4.6 in estimated inflation updates for those old construction cost estimates found in the inventory (medium scenario), $5.3 billion in estimated costs to design and administer the cleanup of that damage, and an estimated $3.9 billion in unreclaimed AML damage that is projected to be added to the AML inventory between 2022 and 2036 (medium scenario). The 2021 report outlines the methods and assumptions, all of which are based on historical data from the AML program, such as historic rates of AMLs added to the inventory and historically how much design and admin costs are (relative to construction costs) for an AML project.

Between October 2020 and January 2022, $567 million in unreclaimed AML construction costs were added to the inventory. I have not included those costs in my calculations here because it will require detailed analysis to determine whether those costs are due to updated cost estimates for AML problems that were already in the inventory or if those costs are due to new AML problems that have been added. In my calculations (which were done in late 2020), I have provided estimates for both inflation adjustments and for projected AMLs to be added to the inventory, based on the unreclaimed AML problems in the inventory at that time (Oct 2020). Future research could analyze these new costs added to the inventory in 2021, but for the purpose of this post my estimates from 2020 provide a solid, if conservative, basis for estimating the extent of remaining AML damage.

The $1.1 billion in projected AML fees are based on calculations that apply the new AML fee rates (20% reduced from 2020 rates) to EIA 2021 coal production projections through 2034, using the Reference Case scenario. The 3.5% assumed federal administration costs are based on the official 2022 annual distributions.

[4] Assumes $11.95 billion in AML reclamation occurs between 2022-2036 ($10.873 from appropriations in IIJA after $25 million in inventory updates and 3.5% federal administration costs; $1.1 billion from AML fees projected using fee levels in 2022-2034 AML fee levels in IIJA and EIA2021 Reference case coal production projections), where reclamation is distributed equally across 15 years. Assumes 2.5 state/tribal jobs is supported by every $1 million in AML grants, which is the state/tribal median according to official 2019 reports to OSMRE. Assumes 4.25 OSMRE jobs is supported by every $1 million in AML discretionary funding, which is the 2009, 2010, 2019, and 2020 average according to official OSMRE annual reports. OSMRE AML jobs are funded on a discretionary basis by Congress and have historically been financed by the AML Fund.Assumes $50M (low), $75M (medium), and $100M (high) in annual AML discretionary funding is provided to OSMRE. See Technical Note and page 26 of Dixon (2021) for more details on the basic methodology, though assumed funding levels have been updated for these estimates using the IIJA numbers.

[5] Using IMPLAN U.S. input/output tables, Pollin et al. estimate that $1 million in spending on AML reclamation supported 2.9 indirect jobs and 5 induced jobs in 2018.

[6] IIJA AML grant estimates multiply by 15 each of the 2022 grant distributions announced by the Department of the Interior, February 7, 2022; they do not include funds from future AML fee collections. See page 11 of Dixon (2021) for cost estimates; note that these figures are based on the inventory as of October 2021; the inventory is incomplete and likely a low estimate.