A recent story in the Columbus Dispatch reported that “two small eastern Ohio counties in the heart of Ohio’s natural gas country posted the biggest economic gains among the state’s counties in 2020” and that “other counties in Appalachia also were among the 2020 winners.”

But that’s only true if you measure “winning” by arcane economic statistics like “gross domestic product” (GDP).The problem is, if you measure winning by things that really matter to the people living there, like jobs and income and whether or not their friends and family members are staying or moving away, then Ohio’s natural gas counties didn’t just lose, they were trounced compared to the rest of the state.

The story told us that, as most Ohio Counties plunged into recession, Monroe, Harrison, Jefferson, and Belmont Counties ended the year with some of the state’s highest GDP gains, their economies “buoyed [by] hydraulic fracturing.” But a closer look at the economies of Ohio’s largest gas-producing counties reveals the depressing truth about the gas industry and its economic impacts.

Job Loss, Population Decline, and Sluggish Income Growth

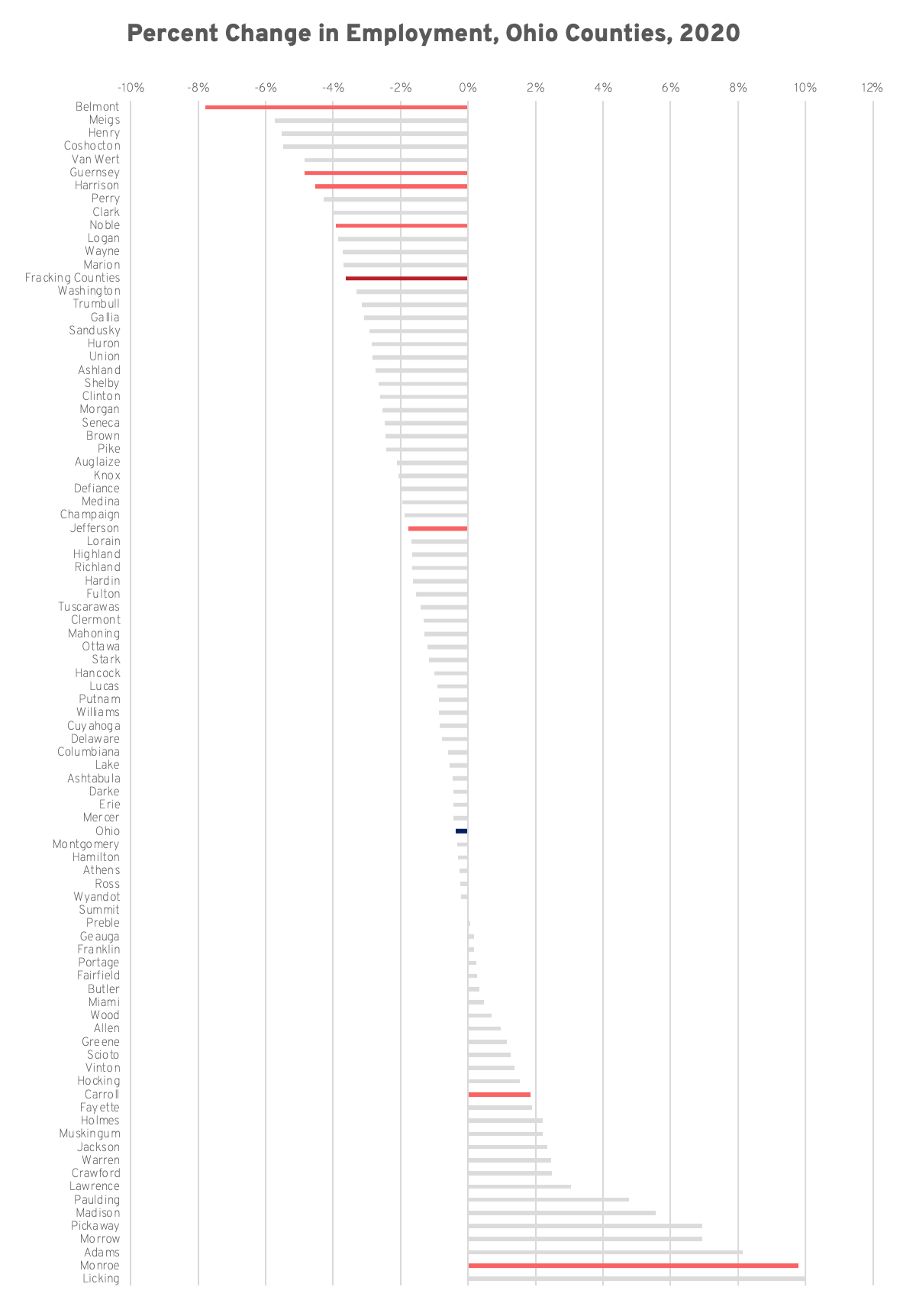

In 2020, at the same time Ohio’s fracking region was leading the state in economic output, it was hemorrhaging jobs. Collectively, about 2,100 jobs were lost in these counties, nearly ten times the rate of job losses statewide. Belmont County, Ohio’s largest gas-producing county and fifth-fastest growing economy, lost 8% of its jobs last year, the worst employment drop in the state. Of eastern Ohio’s cluster of gas-producing counties, only Monroe County posted job growth in 2020.

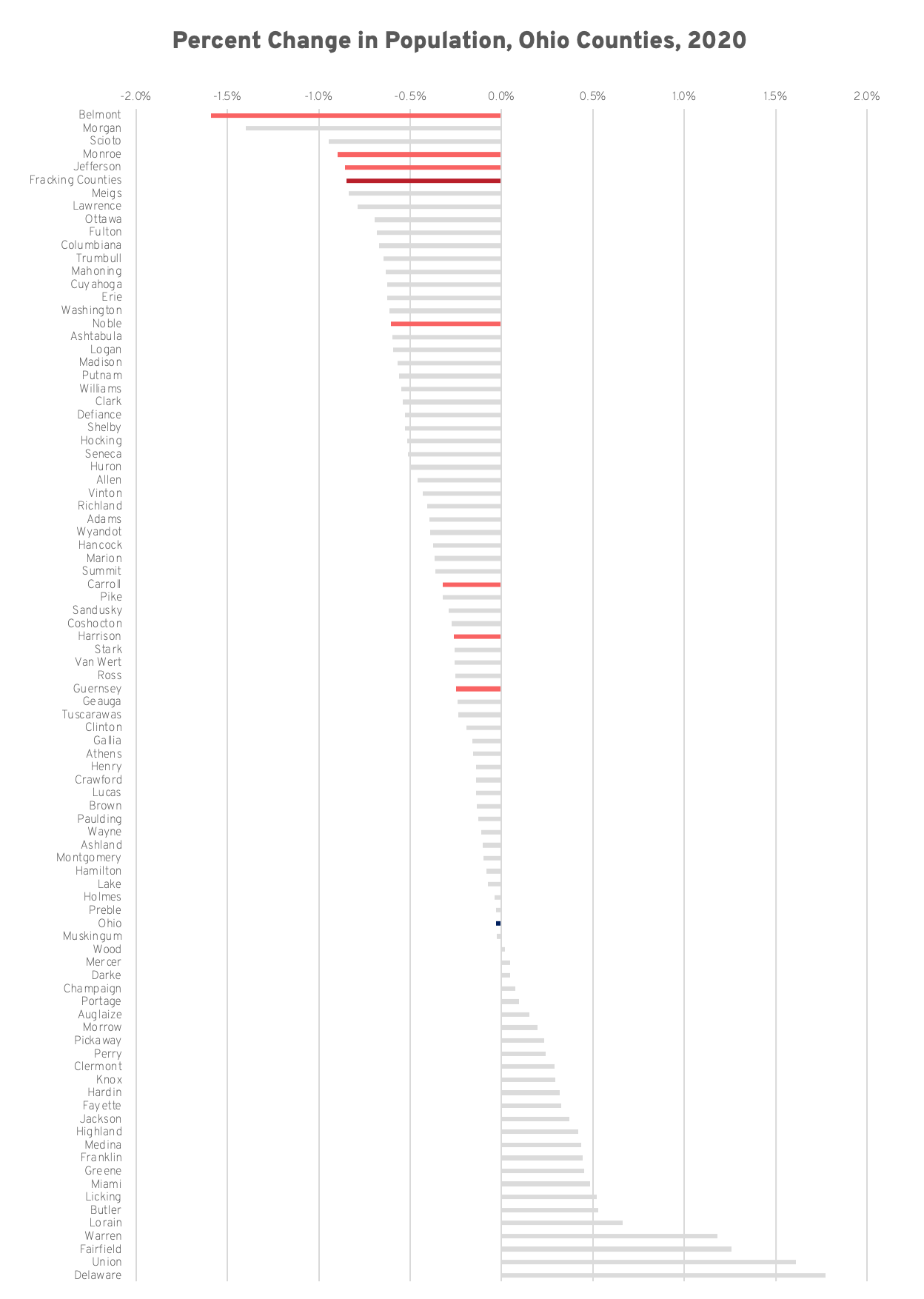

Population loss was just as bad, with Ohio’s natural gas counties suffering some of the state’s most severe population declines. Collectively, these counties lost more than 2,000 residents in 2020, a rate of decline more than 30 times the state average.

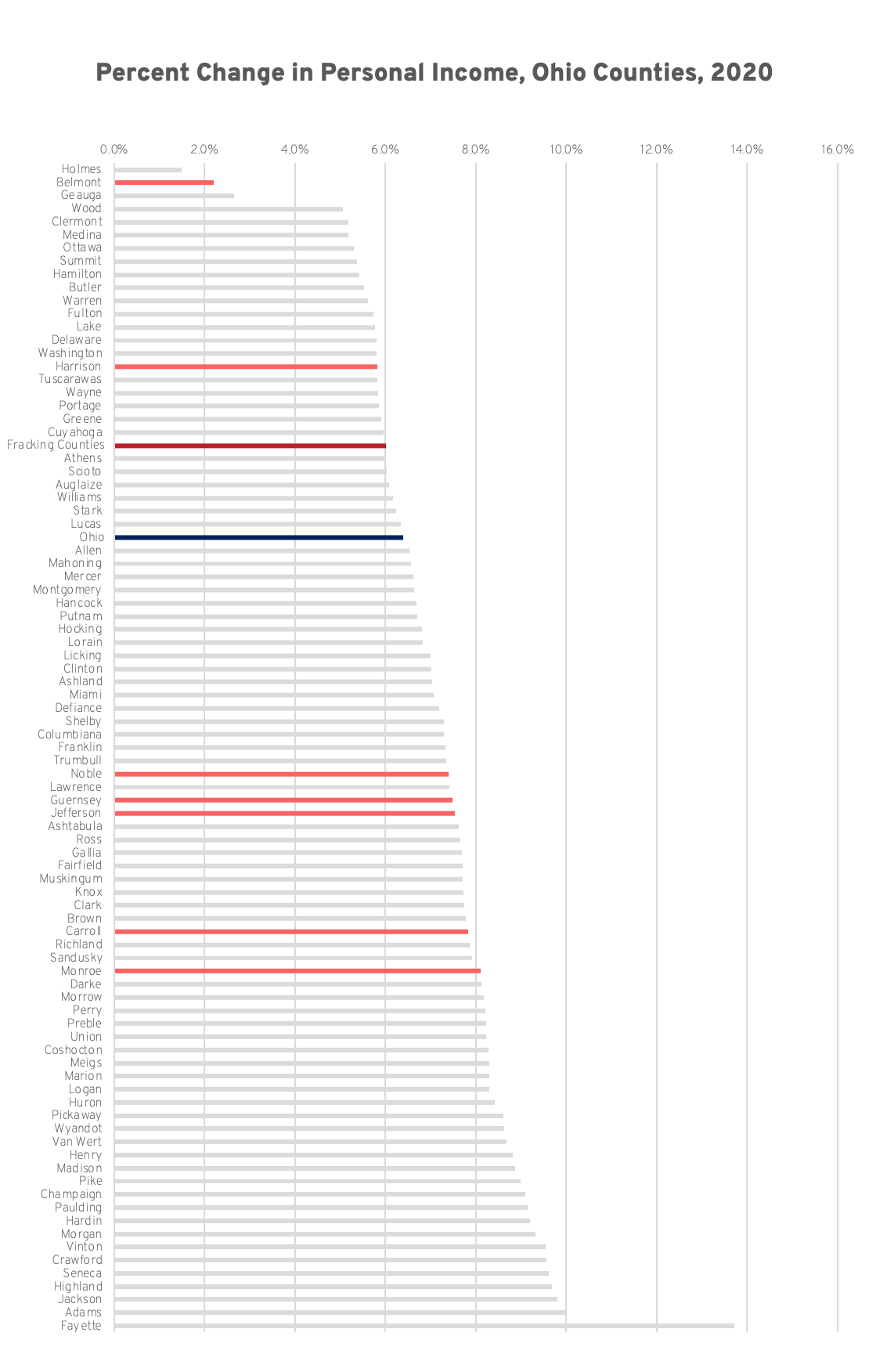

Only in personal income did Ohio’s natural gas counties achieve even mediocre results, still falling short of the state average of 6.4%.

All in all, what accounts for the drastic discrepancy between economic output and employment, personal income, and population? How could the state’s strongest performing economic counties fare so poorly on the measures of local economic prosperity that actually matter to working families?

According to research from the Ohio River Valley Institute, this disconnect has plagued gas-producing counties since the beginning of the Appalachian fracking boom. From 2008 to 2019, the 22 largest gas-producing counties in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia collectively generated GDP growth upwards of 60%, a rate more than triple the national average. Yet, at the same time, these counties saw their share of the nation’s jobs, personal income, and population decline.

It’s an acute symptom of the resource curse—cases of economic growth failing to trigger growth in broadly shared prosperity. Unfortunately for eastern Ohio’s gas-producing counties, the disease is one that’s intrinsic to the gas extraction industry and can’t be cured with more investment or development.

There are several factors that have systematically prohibited the natural gas industry from generating local prosperity in Appalachia. For one, very little of the billions of dollars invested in regional natural gas development since the beginning of the fracking boom—and the millions of dollars invested in Ohio’s fracking counties in recent years—actually enters local economies. Many of the dollars invested in and generated from the natural gas industry finance capital development, whereas a relative pittance goes to labor. (Between 2008 and 2019, just 21% of incremental GDP generated by the region’s largest gas-producing counties was taken home by workers as personal income, according to an analysis by ORVI Senior Researcher Ted Boettner.) Moreover, a significant portion of Appalachian oil and gas labor—estimates vary, but range as high as 70%—is brought in from outside the region, and those workers tend to spend relatively little of their earnings in the local economy.

The natural gas industry is also highly susceptible to fluctuations in commodity prices, subjecting investors and symbiotic industries to cycles of high risk and the potential for bankruptcy. The volatility of the natural gas sector has discouraged the “downstream” investments that many analysts predicted would comprise a large portion of the fracking boom’s economic benefits. Royalty payments and resulting economic activity have also underwhelmed projections.

Lastly, the process of natural gas extraction is highly pollutive, wreaking harm upon local economies—not to mention residents—in the form of externalized environmental and public health costs, a compromised residential quality of life, and a devalued quality of business environment.

Generating economic growth that can actually be realized in local economies and enjoyed by local families will require a hard pivot from continued natural gas development. But it is possible. To learn more about replicable strategies for sustainable economic development that are already producing striking, real-world results, check out the Ohio River Valley Institute’s Centralia Model for Economic Transition in Distressed Communities.