Sometime soon, Shell’s petrochemical plant in western Pennsylvania will finally begin operations, churning out millions of pounds of tiny resin pellets for plastic manufacturing. Despite a barrage of hype about a large-scale petrochemical buildout in Appalachia that was supposed to produce an economic “renaissance,” it was the only project ever to break ground in the region. Hindsight clarifies why.

In a nutshell, it’s because Appalachia is not particularly competitive with the more robust petrochemicals-to-plastic industry hub on the Gulf Coast, and the industry as a whole is facing headwinds. A November 2021 report by the Ohio River Valley Institute called into question the economic viability of Appalachia’s long-planned petrochemical buildout. The report’s authors concluded that demand for plastics will be far more modest than the industry would like. Driven by high levels of concern about plastic waste and a broad appetite for limiting plastic use, three interlocking factors conspire to spell trouble for the petrochemicals-to-plastics industry: product bans, public opinion, and corporate statements.

In a series of three articles, we are examining each of these factors. The first installment clocked the breakneck pace of plastic product bans in jurisdictions around the globe. The second chapter noted that these legally-mandated bans on plastic tend to be very popular. In this final piece, we will see that a surprising number of consumer brands and packaging companies plan to sharply reduce their use of “virgin” plastic made from fossil fuels. Taken together, these developments spell trouble for projects like Shell’s Pennsylvania ethane cracker, which will use gas liquids from fracking to produce material for plastic products.

The largest US trade association for manufacturers of packaged consumer goods, the Consumer Brands Association, is pledging to increase recyclable content in plastic. According to its website, the 25-largest companies in the sector have made commitments to increasing recyclable content, minimizing packaging, or reusing material. In fact, 80% of the Association’s companies are working toward fully recyclable packaging for all of their products by 2030 at the latest.

There’s reason to believe that many consumer-facing brands are sensitive to public opinion about plastics. That’s why a dozen or so major retailers including CVS, Dick’s Sporting Goods, Dollar General, Kroger, Target, and Walmart have signed on to an initiative called Beyond the Bag. These companies are not necessarily looking to phase out single-use plastic bags – to the contrary, they may actually be trying to forestall such efforts – but the effect on the petrochemical industry could be much the same as if they were. If it is successful, the initiative will sharply reduce the use of virgin materials (and greenhouse gas emissions from manufacturing bags), directly undercutting the business model of ethane crackers like the one in Pennsylvania.

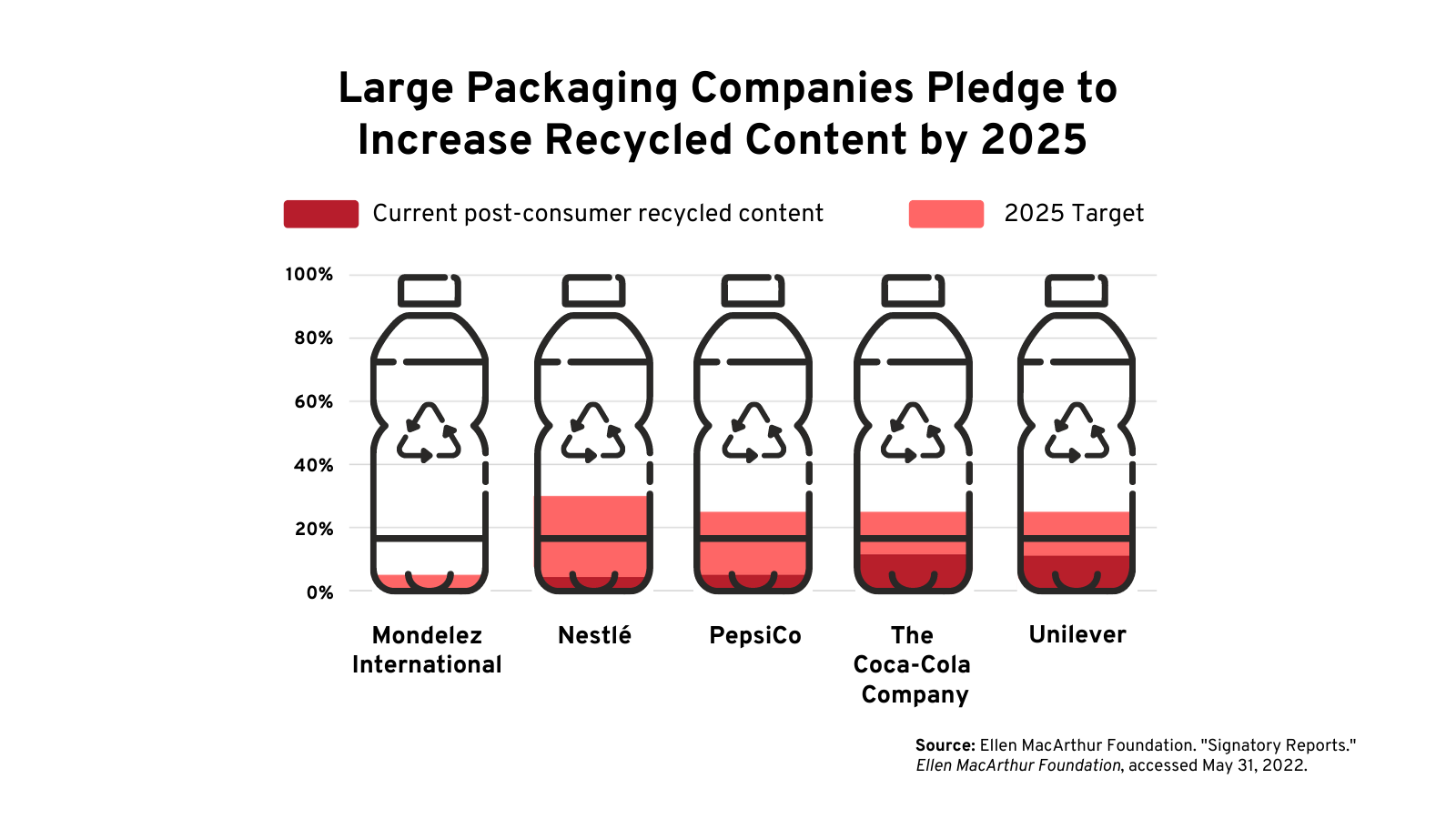

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation recently created the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment in collaboration with the UN Environment Program. So far, 500 firms have signed on, representing fully 20 percent of the users of all plastic packaging produced globally, including companies like L’Oreal, MARS, Nestle, PepsiCo, Coca Cola, Unilever, and Walmart. Efforts like this one are sometimes criticized as “greenwashing” and, in fairness, the Global Commitment is non-binding and relies heavily on recycling plastic rather than phasing it out. But whether it is greenwashing or not, commitments like this are a sort of weathervane. Successful consumer brands are keenly aware of their reputational risks and there is now little doubt that they see their association with virgin plastic as a liability.

It’s even true for the colossus of retail sales, Amazon, which has recently made a range of commitments to curtail plastic in its operations in major markets around the globe. In 2020, Amazon committed to make Amazon device packaging 100% curbside recyclable by 2023 and to eliminate single-use thin film plastics in packaging in India by using paper cushions instead of bubble wrap and air pillows, a pledge made in 2019. Then, in 2021, Amazon announced that it would (in most circumstances) reduce the use of plastic packaging in Germany, switching from single-use packaging to paper bags. Amazon France made a similar commitment in 2021, replacing plastic pouches used for small items with paper bags or envelopes. And in North America, Amazon pledges to expand use of paper padded mailers to replace mixed paper and plastic mailers by the end of 2022. Finally, the company says it is increasing the recycled content of plastic bag films from 25% to 50%, and from 15% to over 40% for plastic padded bags.

Meanwhile, Nestle, the world’s largest food company, said it would spend up to $2 billion to address the plastic crisis, investing in technology to incorporate more recycled plastic packaging in its products and reduce the use of new plastics by one third over the next five years. PepsiCo has launched a new initiative that aims to reduce virgin plastic use per serving by half across all brands by 2030 and to use 50% recycled content in all its plastic packaging. And Unilever is committed to halving the amount of virgin plastic used in its packaging. A list like this could go on for pages.

Of course, none of these corporate commitments will solve problems of plastic waste. And, there is reason to be skeptical of plastic recycling initiatives, given their checkered history. A groundbreaking investigation by NPR and Frontline in 2020 found that the fossil fuel industry had systematically misled the public, encouraging consumers to believe that large-scale plastics recycling was effective and practical, when in fact only a small fraction of plastic was actually being recycled. In fact, the United States recycled just 5 percent of its post-consumer waste in 2021.

Yet all the waste in the current system means that there is enormous potential for improvement. And the breadth of corporate initiatives to address that waste poses a potentially serious threat to the petrochemical-to-plastics industry. If these initiatives are even partially effective, they will reduce total plastic consumption while tilting the market toward recycled materials rather than the virgin materials ethane crackers like Shell’s would produce.

Making matters worse for the fossil fuel-based petrochemical industry, new competitors are cropping up, including manufacturers of bioethylene – ethylene created from bio-ethanol, rather than fossil fuel hydrocarbons – which is already commonly used in food and drink containers, as well as some bags. As energy industry analysts at RBN explain:

“Any producer looking to move into bioethylene production would expect at least modest premiums, given the growing demand for products not based on fossil fuels and the small scale of production to date. For example, Toyota Tsusho — the trading arm of the Toyota Group, which includes Toyota Motor — has committed to buying bio-polyethylene from Braskem’s plant at premiums of 30%-50%.”

Plus, as RBN points out, bioethylene is actually a superior material with fewer impurities than natural gas- or oil-derived ethylene, which could make it preferable for use in medical products or electronics. While there are reasons to be concerned about the environmental impacts of bioethylene, it’s just more bad news for the backers of conventional petrochemicals.

Even as Shell’s petrochemicals-to-plastics plant starts up in Beaver County, its future does not look bright. Driven by a deep and widespread public skepticism of the industry, bans on plastic products are multiplying around the globe, everywhere from small towns to whole nations. Now, hurrying to catch up with their customers, retail brands and packaging companies alike are shifting quickly away from virgin plastic. These factors help explain why Appalachia’s much-hyped “petrochemical renaissance” never materialized, and why banking on the industry to provide economic growth is a strategy likely to fail.

Continue Reading:

Part 1: Why Worry About the Future of the Plastics Industry? Bans.

Part 2: Why Worry About the Future of the Plastics Industry? Public Opinion.